Nine-year-old Olivia Pratt-Korbel was murdered in her Merseyside home on August 22, 2022, the innocent victim of what has been reported to be a confrontation between two people which had spilled from the streets of Liverpool into her family’s house. The child’s mother was also wounded.

In the wake of Pratt-Korbel’s tragic death, news reports have focused on the extent of gun crime in the UK. A recent report in the Guardian revealed that Home Office figures show an increase in recorded gun crime in two-thirds of police force areas in England and Wales.

Government statistics show that for the year ending March 2021, the number of offences in which firearms (excluding airguns) were reported by the police in England and Wales to have caused injury stood at 5,709. Out of 5.4 million total recorded offences, that represents only 0.1% of recorded crime. The numbers also show that gun crime has generally been falling overall since around 2004.

Gun crime carries a devastating symbolic significance. As my research into gun crime worldwide shows, it has the potential to signal a descent into chaos and brutality where violent criminal authority may prevail. In order to tackle it effectively, in any context, we need to understand how many criminal firearms there are, where they come from and how they are being used. Doing so, however, is never simple because it means trying to count what is both illegal and hidden.

How many guns there are in the UK

Rates of gun crime are best approached through the interaction of three sets of factors: illicit gun supply, demand for criminal firearms and police action. The UK has some of the toughest gun laws in the world, but laws are only part of the equation. Criminals break laws, laws require consistent and effective enforcement – and social contexts matter.

Two types of illegal guns have tended to preoccupy gun control researchers: so-called “grey” firearms. These tend to be souvenirs and antiques, often hidden away or forgotten by their owners and are deemed to pose little threat. The threat tends to come from illegal weapons in the possession of offenders. Unless the gun is used in a crime and recovered by police or is fired during the commission of a crime and ballistic trace evidence found, many of the illicit guns will remain largely unknown.

The National Ballistic Intelligence Service (NABIS) took our understanding closer to the core of the problem by identifying “criminally active” firearms from the moment an illegal weapon is first recorded as having been fired or reported, or when ballistic evidence of it is identified. NABIS research has found that about 90% of firearms are only ever used once. Those which do not resurface for 12 months then fall off the “criminally active” list. Only a small percentage of firearms are used used multiple times.

In 2012, NABIS told US journalists that criminally active firearms in the UK numbered around 1,000. This was lower than many had perhaps assumed but it is still instructive.

First, given the 12-month cutoff point, beyond which NABIS considers a weapon no longer criminally active, there are likely to be many dumped guns out there –- although a firearm rusting away at the bottom of a canal may be of little real criminological interest, except perhaps in helping to solve historic offences. And second, there would seem to be sufficient supplies of weapons coming into the country to replace those which have fallen off the criminally active list, given the 90% disappearance rate.

Where the UK’s guns come from

With the exception of the so-called “ghost guns” popular in the US (unserialised and untraceable DIY weapons, often using 3D-printed parts or kits bought online), virtually all firearms start out as lawful products in their countries of manufacture. That does not mean they may be lawfully exported.

Turkey and a number of other European countries permit the manufacture of alarm guns designed for household crime prevention and blank firers. These realistic replica guns and collectables are designed to fire only blanks, sometimes advertised, rather unconvincingly, as “bird scarers”, but mostly prohibited in the UK by virtue of being readily convertible to live firing. However, precisely because of this and the fact they are relatively inexpensive to acquire, they are attractive to would-be offenders.

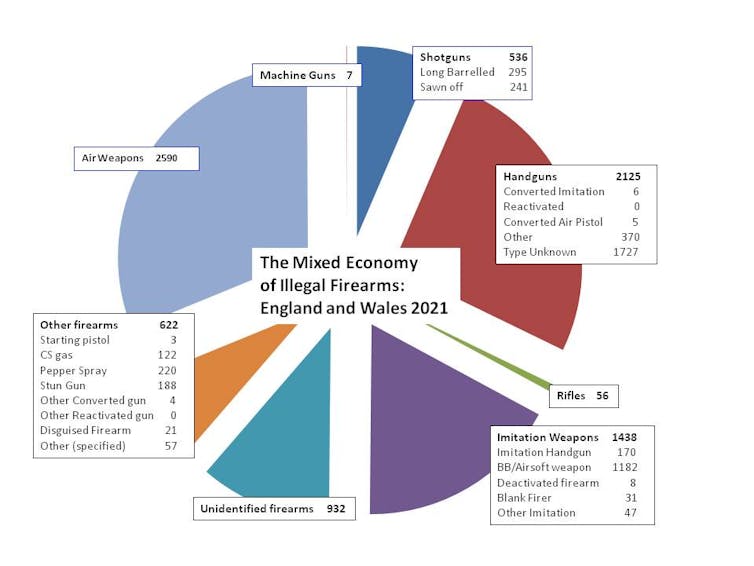

Of those illicit firearms recovered to date, a large proportion have been converted weapons. The rest are reactivated weapons or recycled antiques, original factory-quality weapons, or shotguns that have been stolen from their lawful owners and sawn off.

There are also a host of air-powered, replica and imitation firearms, which, because handguns are only fired in less than one-fifth of gun crime incidents, will often suffice for opportunist robbers. They are essentially “frighteners” rather than “shooters”.

On the other hand, Cleveland Police, one of the force areas reporting a significant increase in gun crimes, has reportedly attributed it to a rise in the use of “slam guns” – or homemade firearms – by drug gangs. The corollary of this, of course, is that if offenders are resorting to such junk weapons, it suggests that fully operational firearms are quite hard to come by.

The persistent demand for guns

Weapons find their way to the UK in much the same way as drugs, concealed within other cargoes, conveyed by traffickers and organised criminals, via dark-net sales and fast-parcel delivery services. They are sometimes also smuggled in small numbers by overseas travellers (firearms control researchers refer to this as the “ant trade”).

In the past, returning military personnel were responsible for a small influx of souvenir weapons. More recently, as I have shown, a consistent flow of firearms trafficked from south-east Europe and the Balkans has also been identified, with some weapons making it to the UK.

If gang-related violence dipped during lockdown, rates are rising once again. Criminals have been able to profit from border controls being affected by the post-Brexit chaos affecting ports and other points of entry, the growing fast-parcel trade and austerity cuts.

Research has long shown that deprivation, underemployment and contraband economies (drugs, in particular) are drivers of violent crime. And police commentators have argued that funding cuts have seriously affected their ability to act.

This has contributed to plummeting sanction detection rates (number of crimes solved). Between 2013 and 2020, these fell by one-third from 31% to 22%, in respect of gun crime offences, and by almost one-half from 25% to 13% for knife crime.

Until recently, gun crime was largely associated with relatively few conurbations, about two-thirds of it concentrated in five or six police force areas. However, some specialist local police operations (Trident in London; Xcalibre in Manchester) have seen officers deployed to other priorities (counterterrorism or knife crime).

Home Office figures report that the recent increases in gun crime are all in those force areas with the historically lowest rates. This might suggest some displacement of gang and gun offending from the hottest locations. Further, rising rates in Kent, Sussex and Hampshire, for example, might also suggest that the guns are following county lines drugs and money routes.

Yet the answer to “how many criminal firearms are there in the UK?” will always be “too many”. It takes few guns in the wrong hands to create a serious violence problem.

Peter Squires receives funding from the EPSRC for a project exploring illegal firearms and gangs in Manchester. Although an Independent criminological researcher, Peter Squires is a member of the UK Gun Control Network established after the Dunblane School Shooting.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.