Slowly, I creep gingerly through thick undergrowth, tiptoeing over fallen branches, careful not to break them. I don't want to make a noise.

Eventually, the bush gives way to a large granite outcrop. We scramble to the top of one of the rocky platforms.

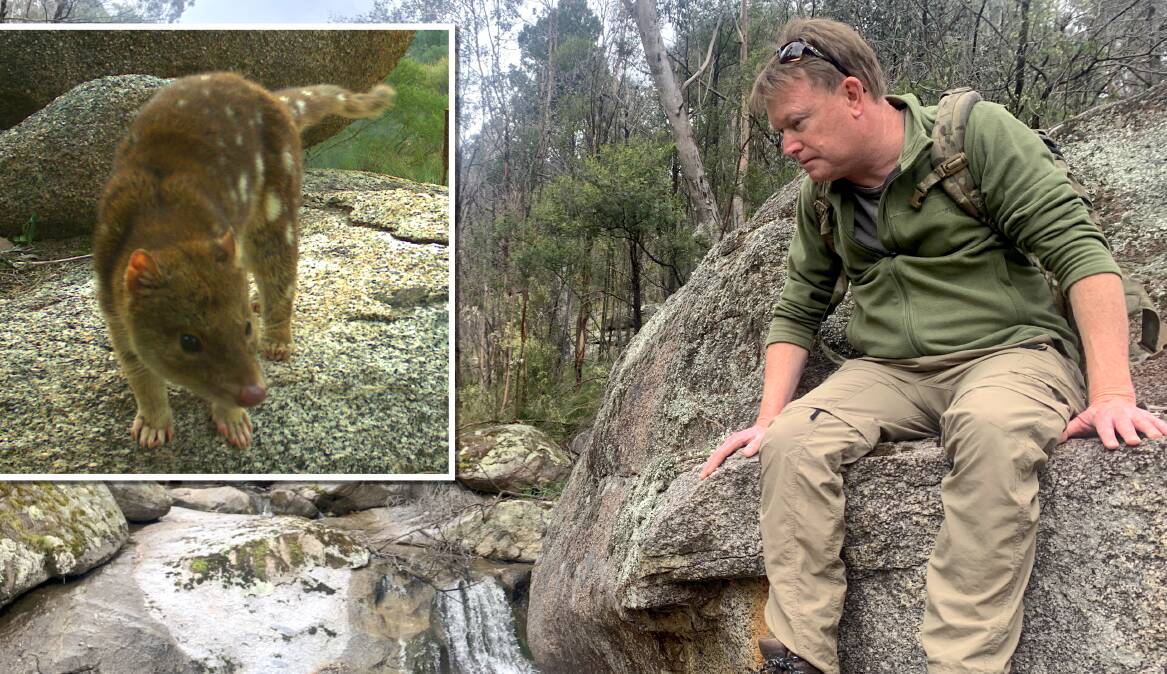

"Wow, just look at the view," I utter in hushed tones to Dr Andrew Claridge who has led me to this knock-out viewpoint in Byadbo Wilderness, a seldom-visited mountainous area that holds up the south-eastern flanks of Kosciuszko National Park.

I'm not sure why I'm whispering. There's no one else within cooee. And what's more, although we're on the track of the elusive spotted-tailed quoll (also referred to as the tiger quoll), as it's predominantly nocturnal, we're not actually on the hunt for live specimens, simply evidence of them.

Byadbo is a second home for Dr Claridge. Over two decades he's hiked through here hundreds of times as part of a long-term collaborative study between the NSW Department of Primary Industries and the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service.

Despite this, during daylight hours he's only rarely captured glimpses of the carnivorous marsupial, which can grow to about the size of a large domestic cat.

"In winter, you could potentially see one out foraging but otherwise it's unlikely you'll see one in broad daylight," he explains.

While he may have only come face-to-face with a quoll in Byadbo on a handful of occasions, that's not to say Dr Claridge hasn't pored over countless images of the cute critters that his team's hidden cameras have captured. And especially on rock platforms like this one where quolls like to visit during mating season to purposefully leave their calling cards.

"Where a rock is used repeatedly by quolls, more often than not you'll find accumulations of scats left by either the local adult female or a bunch of adult males," explains Dr Claridge, adding "these scats can be anything from a small handful to 70 or 80 scats by the end of the breeding season."

Heck, and I thought the five or six of the distinctive small cigar-shaped scats on the rock in front of me was latrine overload.

"The female quoll will also urinate or rub the more sensitive regions of her body on the rock to solicit mates that she wants," the quoll expert reveals.

And by mates, Dr Claridge does mean plural.

"In any given pouch of five or six young there can be different paternities," he explains, adding with a laugh, "in effect these rock platforms are a form of Tinder for quolls".

Gee, that's a lot of swiping right by the male quolls.

But it's not just high on the park's rock platforms that Dr Claridge is searching for signs of quolls. The creeks that flow steeply down from the ridges and into the belly of the Snowy River are also favoured spots by the quolls. "This is mainly due to the existence of prey like possums which are attracted by the vegetation that grows along these nutrient rich corridors," he further explains as he points deep into the river valley below.

Dr Claridge's field trips take him all over Byadbo, through some of Australia's most rugged mountainous country that well and truly lives up to its description in Banjo's famous poem.

Where the hills are twice as steep and twice as rough

Where the river runs those giant hills between

But for Dr Claridge, as magical as the vistas are, it's not so much the lure of landscape, but the desire to understand the life cycle of quolls that brings him back here again and again.

"I love them," he attests, adding "they're absolutely tenacious creatures which suck the life out of every day. They live fast, they die young [females are lucky to see four years, males lucky to see three] and during their time alive they are just hard at it."

After using a variety of techniques to study them including live trapping, microchipping, camera trapping, as well as forensically examining the DNA of scats, Dr Claridge and his team have concluded that Byadbo is a stronghold for the species.

"Regardless of which survey technique we've used, we are still sampling roughly the same number of animals now as we did five, 10, 15 and 20 years ago," reveals Dr Claridge, adding "so they have proven to be robust species, even after the extensive bushfires of 2003 razed vast swathes of Byadbo."

The same can't be said for the plight of the spotted-tailed quoll across the border in Victoria, where, for unknown reasons, in some areas it is hanging on by a thread.

"No one knows why its population has declined so significantly in some locations, it's a genuine mystery," Dr Claridge explains.

However, for now Dr Claridge and his team have their own puzzle to solve right here in the wilds of Byadbo.

"Peak visitation to the rock platforms usually occurs in late autumn and early winter, with mating, birth, and subsequent rearing of pouch young from late winter through spring. In some instances, however, there is a second spike of activity in quolls visiting the rocks, in spring proper. We don't know precisely why this happens but perhaps it's a case of some adult females failing to raise their first litter of pouch young, trying to breed again, and attracting potential suitors."

"But, like a lot of aspects about quoll biology, it remains another mystery to try and solve," he exclaims.

Well, if there's one man who's likely to solve the mystery, it's Dr Andrew Claridge - Australia's spotted-tailed quoll whisperer.

CONTACT TIM: Email: tym@iinet.net.au or Twitter: @TimYowie or write c/- The Canberra Times, GPO Box 606, Civic, ACT, 2601

Everything you need to know about spotted-tailed quolls

What do they eat? Their prey ranges in size from insects to small wallabies and includes possums, rodents, lizards, and birds.

Where do they make their dens? According to Dr Claridge, "with a head full of sharp teeth they can curl up pretty much wherever they want to." For the most part, this is under rock crevices, in hollow rocks on woodland floors, in holes in standing trees, along with disused rabbit and wombat burrows.

How big is their home range? According to radio-tracking research on quolls in Byadbo, adult females have a range of 400-800ha which are mostly non-overlapping with other adult females. Meanwhile, males have a range from 600ha to low thousands of hectares and may overlap in time and space with other males and multiple females. In total, based on these ranges, there are likely to be several hundred quolls in Byadbo and immediate surrounding farms with remnant vegetation.

Are they found in Canberra? There is a sighting in suburban Canberra every five years or so. Typically, it's a male that has wandered from their home in the Brindabellas or further afield and into peri-urban areas like the western boundary of Weston Creek, Belconnen, and Tuggeranong.

How are they different to the eastern quoll? Also solitary like the spotted-tailed quoll, the eastern quoll (Dasyurus viverrinus) is a smaller animal and was once common in many parts of South-East Australia. The range of the two species of quoll used to overlap but due predominantly to predation from and competition by foxes and feral cats the eastern quoll has been considered extinct on the mainland since the 1960s. In 2016, it was reintroduced into fenced sanctuary at Mulligans Flat. There have also been attempts to reintroduce it to the wild, including several years ago in Booderee National Park, near Jervis Bay. The eastern quoll remains sometimes locally common in Tasmania where there are no foxes.

WHERE IN CANBERRA

Rating: Hard

Clue: One of the earliest European settlements in the area

How to enter: Email your guess along with your name and address to tym@iinet.net.au. The first correct email sent after 10am, Saturday 1 October, wins a double pass to Dendy, the Home of Quality Cinema.

Last week: Congratulations to Leigh Palmer of Isaacs who was first to recognise last week's photo as the Guthega Surge Tank. The conspicuous concrete tank is part of the Snowy Hydro Scheme and mitigates pressure variations due to rapid changes in the velocity of water. It was an easy win for Leigh who regularly passes it on hikes to the "Schlink Hilton", a fibro mountain hut 2km west of Schlink Pass, between the Guthega/Munyang Valley and the plains heading to Jagungal.

SPOTTED

The large granite outcrops regularly visited by spotted-tailed quolls in the Byadbo Wilderness are also an attractant for all manner of other species, including lyre birds and dingos.

According to Dr Claridge, "in winter dingos sometimes take advantage of the rock platforms, which have been heated-up by the morning sun," adding "why wouldn't you utilise a feature like that to curl up on and to keep warm?" I guess it's like a natural electric blanket. That is, until the sun goes down.