Suwałki Gap and Vilnius, Lithuania – In Vištytis, in southwestern Lithuania, the atmosphere is tranquil.

But this small sleepy town, home to verdant meadows, a lake, and quaint cottages, has found itself at the centre of geopolitics this year, after Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24.

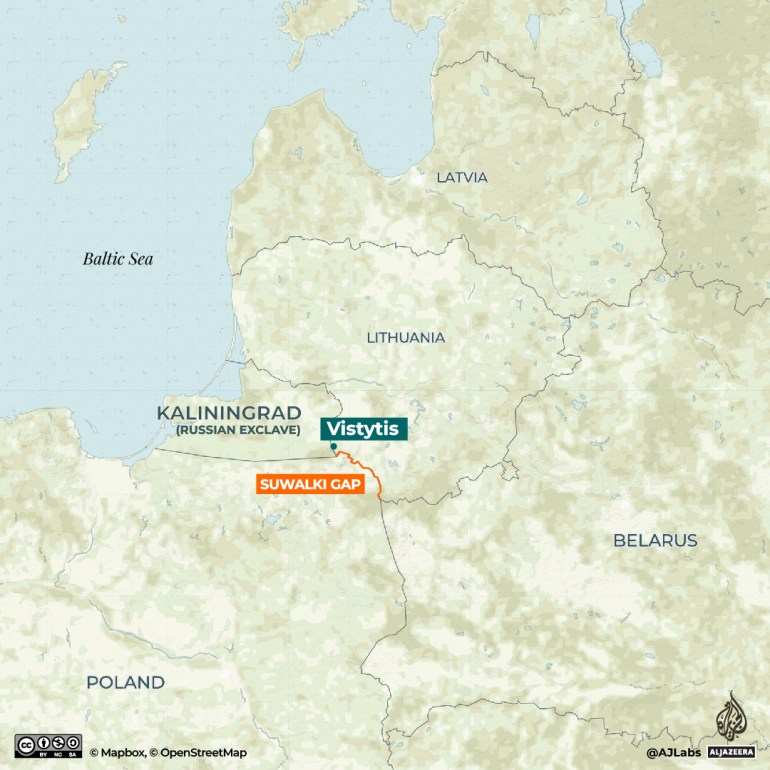

Vištytis is on the frontier with the Kaliningrad region – a heavily militarised Russian exclave bordering Poland and Lithuania, where Moscow reportedly keeps nuclear weapons.

Residents often see Russian border guards patrolling the border from their houses.

“We take a swim in the lake just 10 or so metres from the barbed wire fence. Sometimes, we can hear the border guards on the Russian side playing music. When that happens, we have a barbecue and dance to the music that’s coming from the tower,” Irina Skučas, a factory worker, told Al Jazeera.

Living by the border

She and her husband Gediminas have coexisted peacefully with their Russian neighbours for about 20 years.

“The Russians have never done anything to us,” she said.

“But when they closed the border to Russia, a lot of cheaper construction supplies stopped being transported from the Russian side. So, for example, nails we use to drill into walls or hang electrical cords, they now cost three times as much because they come from somewhere in Europe, not from Russia.”

Her town sits in the northwestern tip of the Suwałki Gap – a 100-kilometre (62-mile) strategic stretch of land along the Lithuania-Poland border, connecting Russia’s Kaliningrad to Belarus.

Pundits have called it the “most dangerous place on Earth”.

But locals – many of whom have lived through and vividly recall Soviet times – find the claim laughable.

“Everyone is using fear-mongering language on all sides. Simple folk like us really see it from a different perspective,” Gediminas told Al Jazeera. “They say we’re at war now, but it’s not the reality that we see here.”

After Moscow rolled troops into Ukraine, Lithuania imposed EU sanctions and shut its borders to Russia. Its military has also been preparing for any potential Russian aggression.

“We must start thinking as if we are living in a war,” Arvydas Anušauskas, Lithuania’s defence minister told reporters in Rukla, a small central town, on October 8.

In late September, Lithuania’s Rapid Reaction Force – established in 2014, comprising two battle groups – was also put on high alert following Putin’s partial mobilisation order.

Yet, some 90km (56 miles) away from Irina and Gediminas on the southern tip of the Suwałki gap, 24-year-old Neringa Kilmelyte shares a similar view.

Neringa lives in Kapčiamiestis, a village next to the Belarusian border, which was also a friction point during last year’s border crisis, housing some of the displaced people coming in from Belarus in the local school.

“Here you just live day by day, without planning in advance. That’s Lithuanian mentality,” Neringa, who returned to Kapčiamiestis to give birth to her son, Joris, told Al Jazeera.

“In Alytos, where I lived before, I already saw armoured vehicles going by regularly so it’s a part of everyday life,” she added.

Joining the army

Many of Neringa’s friends joined the army or volunteer militias like the Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union as the Russia-Ukraine war heated up.

According to the Union, thousands more requests to join have been made this year. One volunteer told Al Jazeera there is a waiting list of two and a half years.

In 2015, conscription was reintroduced in Lithuania following the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea.

Those drafted are currently training with a newly formed German-led combat unit in Rukla.

The brigade was set up following a NATO summit in Madrid, which overhauled defence planning in the Baltics to repel any attack in real-time.

“One thing is certain. The current situation means we need to do more together,” German defence minister Christine Lambrecht told journalists while inaugurating a permanent German command centre in Rukla.

In the Lithuanian capital Vilnius, Vaidotas Urbelis, policy director at the defence ministry, told Al Jazeera that his country is drafting 4,000 new conscripts per year.

“The worst case scenario is a large war in Europe and there are some indicators it could happen. Nobody can predict what Putin will do. We must make sure the military is ready. That means more manpower and reservists,” he said.

“Militarily we don’t distinguish between the Belarusian and Russian military. Lukashenko has no control over his army, it’s just an extension of Putin and Russia,” he added.

“It’s an old saying from Roman times that if you want peace, prepare for war.”

Besides defence tactics, to help civilians, the interior ministry has also published a map with shelters and safe buildings, for use in case of emergency.

Some civilians have gone a step further.

Vytas, a former military man in his 40s, has resurrected an abandoned World War II bunker.

In the unlikely scenario that Lithuania is attacked, that’s where he’ll go.

“This isn’t going to protect me against a modern-day bomb. Weapons are too sophisticated today,” he told Al Jazeera.

“But the thick walls of the bunker would give some protection against radiation, though probably not if a nuclear warhead was dropped close by. I don’t think you’d be safe if that were to happen.”

Meanwhile, others like 33-year-old Pawel Andrul, have adopted a relatively calmer attitude.

“It is somewhere in the Europeans’ DNA not to be afraid,” Andrul, who lives in the Polish town Suwalki of the Suwalki corridor, told Al Jazeera.

“Concerns about this Russian aggressor are present in Polish society all the time,” he added.

Known for its picturesque landscapes, synagogues and churches, Suwalki is a multicultural place.

But Poland’s contentious history with the Soviet Union is etched in the minds of Suwalki locals.

“Polish people here do not like Russians. They have not forgotten massacres like the Katyn,” he added.

The Katyn massacre of the 1940s took place when Poland was under Soviet Rule and involved the mass executions of thousands of Polish military officers.

Andrul highlighted that if Russia were to invade any of Poland’s neighbours and target towns which dot the Suwalki gap, Warsaw would step in to help.

“It is Poland’s business to do so,” he said.

Neringa shared a similar sentiment.

“I feel confident other countries will help if the Russians come here. Let’s not pretend that Lithuania can defend itself against an invasion,” she told Al Jazeera.

A stone’s throw away from Neringa’s house, 70-year-old Jonas Sukditis and his 68-year-old wife Vida have been following the war in Ukraine on their television.

Commenting on Russian President Vladimir Putin’s latest threats towards Ukraine and other NATO countries, Jonas told Al Jazeera: “We’re just small pieces. Chess pieces, really. For the bigger powers to wage conflict against each other.”

He highlighted that “war” was in their blood and that he and his wife were prepared to face any emergency.

“We’ve seen so much of this stuff through history that we have a basement where we could go into if bombs were to drop on us. The basement is full of food supplies and other useful stuff,” he said, stroking his cat.

Fear of war is a distant and low-lying concern – as it’s been for many years – for locals living in the former USSR.

For many like Irina, the bigger worry is that political rhetoric and warmongering take over, and perception becomes reality.

“We’ve experienced so much of this uncertainty throughout history,” said Irina. “So why worry? If the war starts, the war starts.”

Mantas Narkevicius contributed to this report with translation services.