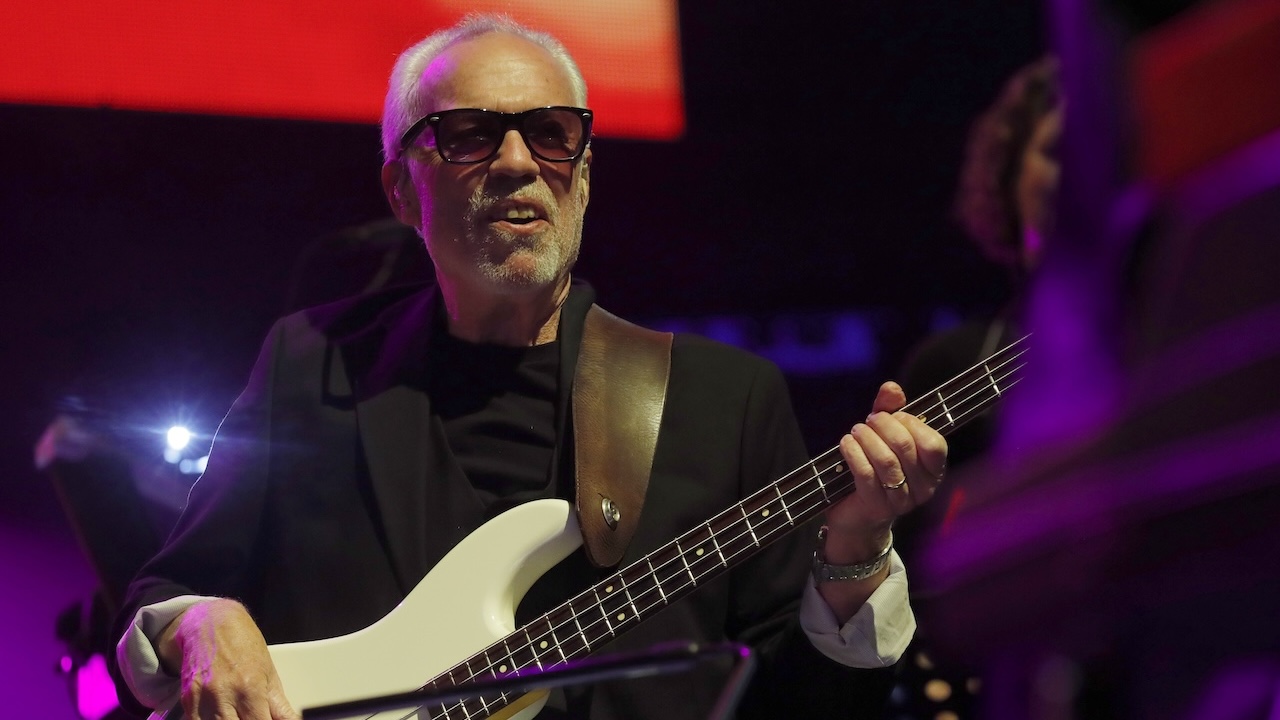

Brooklyn-born Neil Jason’s turn as a first-call New York session bassist coincided with the profession’s peak period for “players” – a time when the studio inner circle was equally adept at jingles and jazz-rock fusion sides.

Jason was discovered by the Brecker Brothers on his first major date for Gladys Knight, who promptly enlisted him for their band in 1978. Albums with John McLaughlin and Bob James followed before he began permeating the pop charts via platters by Kiss, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and Billy Joel, and No. 1 hits ranging from Fame to Girls Just Wanna Have Fun.

Jason told Bass Player, “Until I got my own place, I lived with both Randy and Michael Brecker, and to see the commitment level of these two icons, practicing six hours a day, was the ultimate musical education for me.”

Among Jason’s woodshed-earned, water-shed skills was his slap style – gritty in tone and groove, yet so precise that engineers could forego a compressor to even out his thumps and pops. That sound would reach the radio on Diana Ross’s 1981 chart-topping cover of Why Do Fools Fall in Love.

However, one of Jason’s fiercest fingerboard forays can be found on 1979 instrumental hit Hideaway by saxophonist David Sanborn, who passed away on May 12, 2024.

The studio session took place in early 1979, at Minot Sound, in White Plains, New York. The band – Sanborn, Jason, drummer Steve Gadd, keyboardist Don Grolnick, and percussionist Ralph MacDonald – tracked live, with additional sax, keyboard, and percussion overdubs added later. Jason played his trademark red 1965 L-Series Fender Jazz Bass with new Rotosound strings, and the secret ingredient to many a Jason track: an Ibanez CS-9 Stereo Chorus pedal.

“It was the only chorus that neither degraded nor added to the bass frequencies, while also providing a nice sparkle to the pops on the high end.” As was his practice then, his bass was recorded straight to a direct box, then into the chorus pedal, and then into another direct box, so there would be both clean and effect tracks to choose from. (In this case, only the effect track was used).

The other key to Jason’s woody, growling tone was his preference for favoring the bridge pickup. “At that time, I liked getting a point on my notes, and the Jaco sound was in everybody’s ears, as well. We did a run-through and maybe two takes, and that was it. Neither Steve nor I did any punches or overdubs.”

As the track begins, Jason’s chorus pedal can be clearly heard, both on the long tones and the upper-register peek- outs. This continues at the A-section alto sax melody. With Gadd implying a half-time feel and only chordal padding from the keyboards, Jason’s bass motion is immediately established as the other key voice to Sanborn’s sax. When Sunburn restates the melody, Jason switches to slapping, as Gadd adds pick-ups to his one and three kick pulse.

The song’s chorus launches the full funk, as Gadd introduces backbeat snare cracks and Jason turns up the juice. The key to this section is the two-bar phrase Gadd and Jason settle into. Jason generally improvises in the first bar of the phrase, while catching (sometimes with different note choices) or making reference to the syncopation in the second bar.

Typical of session cats letting loose during the fade is Jason’s finger-plucked upper-register fill. “In pop, rock, and R&B, I would try to develop a bassline with only subtle variations because I wanted it to be felt as part of the song, not a performance within the song. But in a jazz instrumental situation like this, your performance is part of the song.

“Still, listening back now, I can’t believe how many notes I played! I sure would play less today; to slap and slide and land in the right places – what a chance to take in the middle of a live recording!”

Sanborn was less than a year away from the first of his memorable collaborations with Marcus Miller (including a more-uptempo revisit of Hideaway on the saxist’s 1984 disc, Straight to the Heart), but Hideaway and its catchy title track remain the favorite of many a Sanborn fan.

As for play-along advice, Jason stressed, “Listen to and lock with the drums. Steve Gadd’s perfect performance is what makes me sound good.”

“For me, slapping has two main ingredients. The first is that you’re the bassist and the drummer at the same time, so make sure some part of what you’re slapping and popping is continuously rolling along, keeping time. That’s what I got from Larry Graham; when he plays by himself you still hear the drums.

“The other key is you have to listen to and phrase like the drummer you’re playing with. You can’t challenge his or her groove, time, and swing; you have to match and fit in-between where they put their upbeats, how far they lay back, and how they feel the spaces. Do that and you’ll sound like a pocket genius!”