A postcard, a fork, and a skull and crossbones emblem - mundane objects build an absorbing tapestry of life at sea in the early days of colonial New Zealand

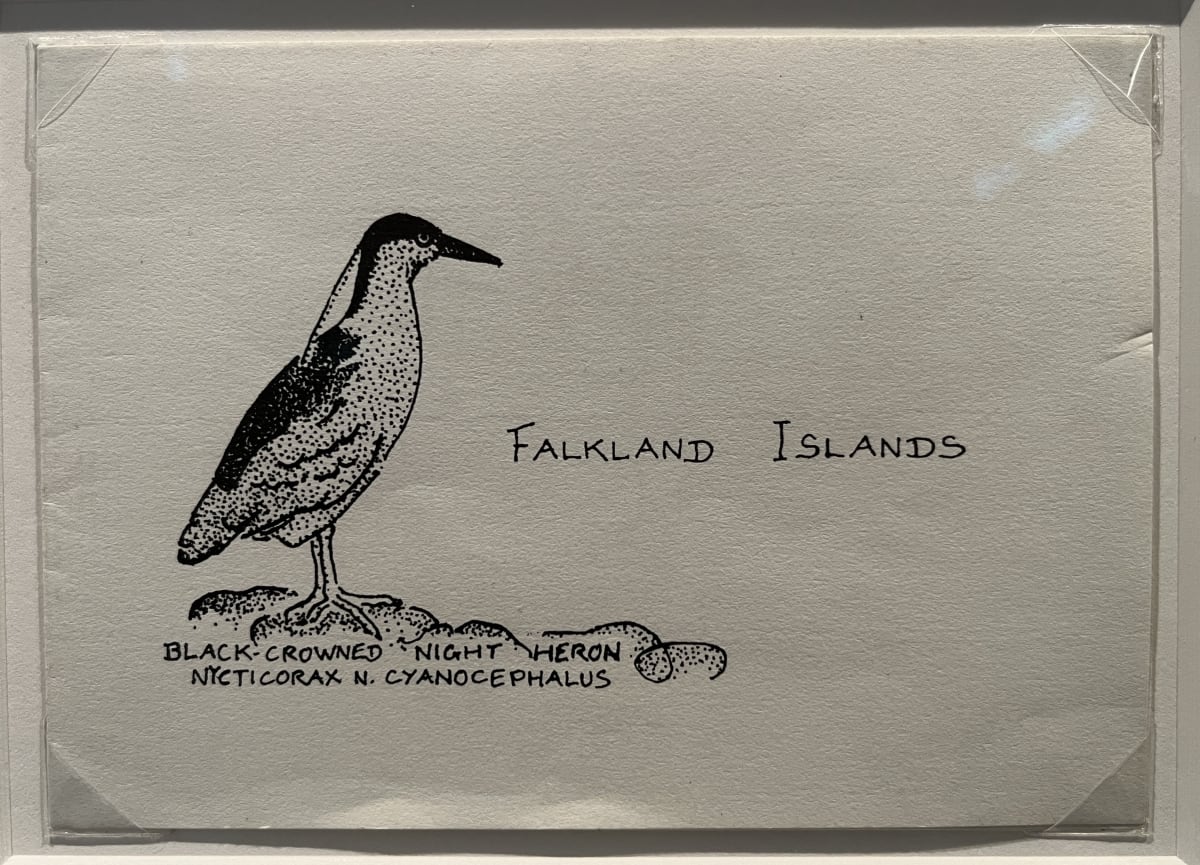

One day in 2021, while New Zealand Maritime Museum collections specialist Nick Keenleyside was cataloguing part of the museum's enormous stock of items, he was surprised to find a homemade postcard from the Falkland Islands with an illustration of a black-crowned night heron.

On its own, it's hardly surprising - a piece of stationery used in correspondence, part of the thousands of pieces of historical ephemera that makes up the museum’s shrine to New Zealand’s close historical relationship to the oceans.

But what made this different was something no member of the museum's curatorial staff would expect to happen - Keenleyside drew the heron himself, as a teenager on the Falkland Islands over 40 years ago.

The postcard found its way into a shop somewhere on the rocky islands off the coast of South America, where it was picked up and sent as a Christmas card to ex-British Merchant Navy sailor Gerry Clark, who was by then running an orchard in Kerikeri and building his own yacht.

Clark was a keen seafarer and ornithologist, known for his seabird research in the icy sub-antarctic islands that form the southern reaches of New Zealand’s maritime territory and circumnavigating Antarctica in his self-built yacht Totorore.

Clark was lost at sea in 1999 somewhere off the coast of Antipodes Island, leaving behind an amassed collection of ephemera and artefacts that his family donated to the museum some 20 years later.

It was then that Keenleyside began going through the collection, only to find his own work staring back at him after most of a lifetime.

Exhibitions curator Jacqui Knowles says strange twists of fate like that are found throughout the new exhibition, which is partly in place to celebrate 30 years of the museum acting as a steward for the history of New Zealand’s relationship with the sea.

“What are the odds of that happening? It was his desk this ended up on as well,” Knowles says.

It’s just one of the many coincidences and unlikely connections that form the basis of the museum’s newest exhibition. Captains, Collectors, Friends & Adventurers opened in early December, the brainchild of museum staff who noticed the myriad of unexpected associations between artefacts, stories and characters in the museum’s collection.

Museum director Vincent Lipanovich calls the sea a great connector of people and stories - and for New Zealand, where the geographical ubiquity of the ocean and the nautical isolation of these islands has placed boats and seafaring at the forefront of our national character, it’s doubly true.

But according to Knowles, being able to link up all of the stories and show the public the massive spiderweb of our nautical history hasn’t always been a doable feat.

Digitisation of the archives has allowed curatorial staff to more easily identify those links and fill out the tapestry of maritime history.

Funding from the Lotteries Commission over the last two years has allowed the collections team to begin digitising items at the museum and its off-site storage facility in Avondale.

So far, around 14,000 different items have been photographed, scanned and uploaded to an online database to broaden access to the public.

“A big part of being able to link these stories came from the digitisation,” Knowles said. “For years we’ve had a lot of stuff in our database just sitting there. You know that they’re there, but sometimes the description can be quite brief. The way that things are stored to make them safe they are often in boxes...to cite it, you have to spend about five minutes unwrapping it.”

Digitisation has also allowed closer inspection of sailors' old photo albums: Knowles points to a photo of keen sailing family the Shakespeares, with the process allowing the team to notice the small skull and crossbones emblems on some of their hats.

“That gave us a clue that it was linked to a boat that Robert Shakespeare built for his family named Pirate,” she says. “It was little things like that - a piece of the puzzle.”

Another figure in the photo kept turning up over and over.

That was Captain John Peter Bollans - commander of the SS Hinemoa, a government-operated steamer that ran the length of the country and further from 1876. The Hinemoa delivered supplies to island communities, serviced lighthouses and ferried government dignitaries.

Knowles says finding out more about Bollons’ adventures was a personal highlight for her.

“Bollons arrived in Bluff as a teenager and was taken in by the seafarer, Tohi Te Marama, after the ship he was crewing on wrecked,” she says. “He worked his way up to the role of Captain and was employed on government steamers that serviced lighthouses around Aotearoa and patrolled the Subantarctic Islands for castaways.”

Bollons himself was a keen collector, and when he died in 1929, his haul eventually made its way into Te Papa.

His life was later fictionalised in memoriam by Bernard Fergusson, the last British-born governor-general of New Zealand, in the 1972 novel Captain John Niven.

The collection shows the intricate backstories that can be hidden in relatively mundane objects.

A fork in a glass box tells the story of a man named Henry Swan, a would-be adventurer who lived alone aboard a yacht moored in Henderson Creek for more than twenty years.

His wife Edith remained on dry land at home in Devonport, and visited weekly by travelling to the city by steam ferry and then on to Henderson by rail.

Journalist Jack Leigh gifted the fork - used aboard Swan's yacht, the Awatea - to the museum after a series of articles covering Swan’s strange tale in the 1990s.

Swan became the central figure of an urban myth about a man who planned to travel around the world on his yacht, but instead hid it up among the mangroves and camped out for a couple of decades.

It’s disputed whether Swan ever really meant to take his yacht around the world. However it is indisputable that his hermitry has earned him a place among the pantheon of strange tales and characters that connect New Zealanders to the sea.