Review: Light: Works from The Tate’s Collection, ACMI

The first room of Light: Works from The Tate’s Collection at Melbourne’s ACMI, begins, cannily, at the end of the Enlightenment – the period of the 17th and 18th centuries characterised by the emergence of the scientific method and the decline of the power of religious thinking.

Beginning in the 18th century and winding up with work from the 21st, it is a show of some 70 works that surveys the many ways light has been important to artists as both the material and content of their work.

Read more: Explainer: the ideas of Kant

Light and the birth of abstract painting

Not surprisingly in an exhibition by Britain’s Tate, J.M.W. Turner is front and centre in this first room.

Turner is commonly associated with his contemporary John Constable, as he is here.

Constable applied himself scientifically to the recording of atmospheric effects. But there is really nothing like Turner’s swirling, highly textured, and downright experimental work of the second half of his career.

Turner’s later work can be abstract to the point where we must rely on the title to tell us what we are looking at – as is the case with Light and Colour (Goethe’s Theory) – the Morning after the Deluge – Moses Writing the Book of Genesis from 1843 (yes, that’s all one title!).

Turner points the way to the shift in the late 19th and 20th centuries away from naturalistic representation as a key value in art.

As the exhibition travels forward in time through its various galleries, it is a delight to find the mid-century abstract photography of György Kepes and Luigi Veronesi.

So often the history of art leaves out the attempts by many 20th century artists to use film and photography for ends other than naturalistic renderings of the world as we see it.

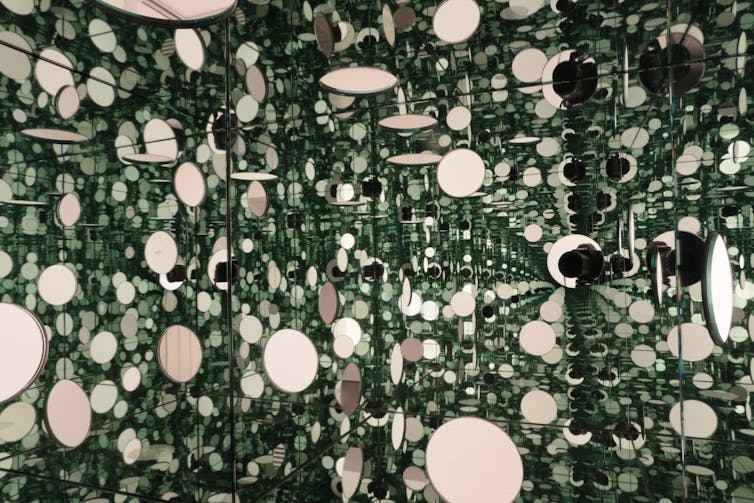

Seated among these works is a Yayoi Kusama sculpture, The Passing Winter (2005), sitting at the centre of the exhibition.

Seriously dotty

With her iconic and cartoony bobbed hair and polka dot fetish, Kusama is occasionally overlooked as Instagram eye candy and grandmother of east Asian cute.

In reality, she has been a deeply serious artist since her emergence in 1960s New York. Her installations can be quite intense, disorientating experiences.

Stereotypically Japanese, Kusama’s craft is exacting in terms of the experiences she creates, and this work is no exception. Using a complex set of mirrors and portals, the work by turns fractures, refracts and reflects the room around it.

As you play with the various portals it offers, the work feels so very precise in its ability to surround you with shimmering dots or echoes of our own circularly vignetted face.

Transported into the world of Kusama’s unique psyche, while remaining at a safely bell-roped distance, I couldn’t help but smile.

Read more: From selfie to infinity: Yayoi Kusama’s amazing technicoloured dreamscape

More circles

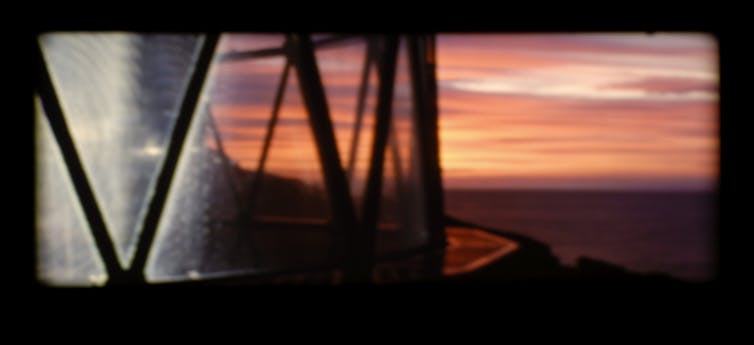

As you approach the end of the exhibition, there is a room dedicated to Tacita Dean’s 16mm film installation, Disappearance at Sea (1996).

In an echo of Turner’s seascapes, Dean creates a deceptively simple, circular portrait of a lighthouse. Like Kusama, all is circles: day to night the lighthouse lamp rotates gravely as the giant film loop chases its own tail.

We have all become accustomed to 4K televisions. We now realise just how orange TV makeup is. Our eyes have also become retrospectively more sensitive to the lack of resolution in earlier formats like DVD and the humble VHS tape. This technological advance made this work feel entirely different now to when I first viewed it in 2001.

The grainy 16mm film, ticking through the intricate looping film projector, foregrounds the ephemerality of light through its precarious physicality.

None of the glassy imperviousness of the digital image, we were looking at a fragile remnant from another time, like the Constables and Turners.

Art as phenomena

This show offers a respite from contemporary art dominated by social concerns.

Even as an insider, I feel contemporary art is, at times, theoretically and politically overburdened.

This comes on the back of a suspicion of aesthetics among many contemporary practitioners and academics (by aesthetics I mean the realm of the sensory, intuitive and prelingual). That’s fine: contemporary art is a broad church, and if art can help with society’s ills, there’s certainly plenty of work to do.

But this is something different, an exhibition which privileges the body and its sensations.

Curated as they are here, these works are presented not to be read for meaning but to be experienced as phenomena (yes, yes, good art can do both).

There is plenty of representational, narrative content amongst what is on show: people and places, moments from myth, imagination and history.

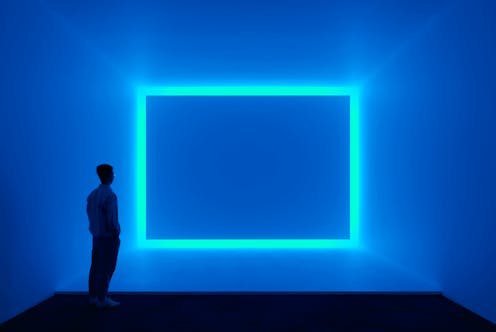

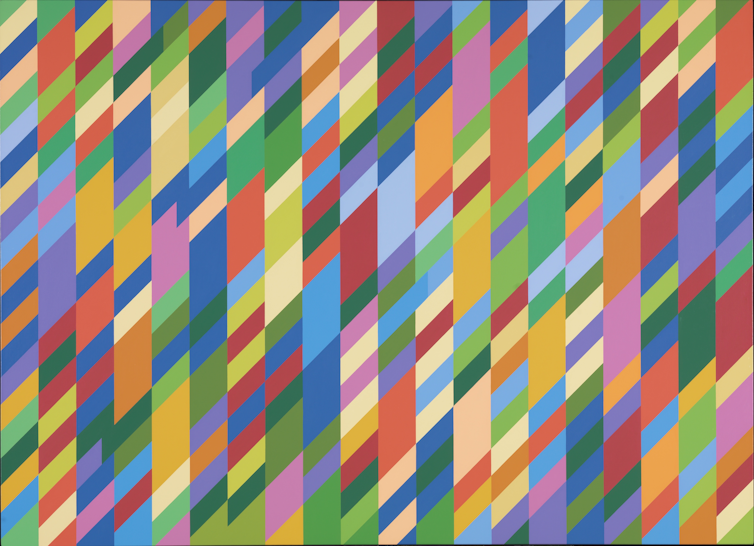

However, for me, this is a show to be felt: floating in front of James Turrell’s Raemar, Blue (1969), sitting surrounded by the circling sparkles of Olafur Eliasson’s Stardust Particle (2014), being hypnotised by Bridget Riley’s Nataraja (1993), or considering the clouds that overshadow Constable’s bucolic (ok, admittedly a little saccharine) scenes.

Light: Works from The Tate’s Collection is at ACMI until November 13.

Read more: James Turrell, a mythic artist in the contemporary constellation

Dominic Redfern has previously had work funded by local, state and federal government bodies.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.