On the writing genius powering NZ's classic soap opera to new heights

TK had agreed to one last shift. TK was happy. TK had a new job and a future to come away from Ferndale. Everything suggested renewal, new stability, peace, closure. And that, in the logic of the soap opera, is always the promise of catastrophe. That the seeming death of Shortland Street character TK Samuels was anticipated by the genre’s elaborate rituals made it no less devastating, however, and no less powerful. TK’s struggle in life against death, uncertain still as this goes online, is one further illustration of Aotearoa’s longest-running show entering a radically new and radically exciting period.

A recap. It’s been quite the year in Ferndale. Shortland Street medical centre was bailed out, and then subject to hostile takeover, by a sinister Christian cult. That was after the fire (don’t ask); that followed shifting positions at the top, as Chris Warner and TK Samuels worked as CEO; fallout from the fire and the cult and the casualties (it all connects; stick with us) led to a grudge. That grudge led to a troubled young man beating up TK for kicks and filming the whole thing, then getting boxing lessons to help him back on track with his life and then, recently, returning to the hospital to try and gun everyone down. Amidst all the slaughter (there was a lot of blood) villainous Milo shot TK down. And, everything in that episode and the next led us to believe, we watched TK on life support as his whānau realised all hope was gone. He was supposed to be a dead man.

Milo’s rampage, and TK’s shooting, will surely stand alongside Joey’s leap from that roof and exposure as the Ferndale Strangler, or Nick and Waverley’s wedding, or Toni’s death, as a Shortland Street moment critics and viewers will be discussing for years to come. It’s canonical, comparable to Alan Bradley’s death by tram or Alma’s final moments with Mike Baldwin at her side in Coronation Street in its grandeur and thrill.

Who wasn’t weeping when the decision was made to turn off his life support? The Street is studded with an astonishing array of gifted actors these past years, and Nicole Whippy’s superb performance as Cece brings to mind Joan Sutherland’s mad scenes in opera, in her intensity, integrity and heart. Soap opera, after all, like the nineteenth-century realist novel, strives to capture everything in life itself, all its glories and sentimentality and cruelty and savagery and selfishness and clear-eyed flintiness. We cried because Cece was crying; we cried for TK. But we cried, all along, knowing that we were crying for ourselves: crying for the mourning we’ve done in our lives already, and will need to do again, and, buried close to self-consciousness, for the relief that it’s not us, there, that someone else is on the operating table that day.

Those who don’t understand soaps – or who pretend not to follow their compulsive lurches as we do – scoff sometimes at the genre’s improbabilities and excesses, its murders and marriages. But that’s the point: the pity and the grief of the soap plot-line is always an opportunity for fascinated return. The glory is in the vulgarity. We follow our heroes, and we follow to see them punished.

Shortland Street gives Freud a twist for the era of Land Back: Māori Patriarch against Pākehā Father, in all their rivalry, envy and brotherly love

Psychoanalysis would have much to say about a figure like TK, the energetic, chaotic Patriarch upending the order held by that tamer, vainer, strutting Father Chris Warner, Ferndale’s elder statesman. The Oedpius story is, after all, a tale of regicide. Freud wrote two books on killed fathers, Totem and Taboo and Moses and Monotheism, and TK Samuels manages always to combine patriarchal order – the Law of the Father, expressed so winningly in a mere glance or a shrug through Benjamin Mitchell’s brilliant, physical acting energy – with the disorder of appetite, libidinal urges, disruption.

Sex and death, fortune and misfortune: TK draws them all in, and has done so time and again over the last 16 years. TK’s great ordering principle is whānau, and his great disorder is the energies that unleashes. His possible paralysis, like his prostate cancer, fuses, as his fraternal struggle with Chris over the hospital did in the realm of politics, virility and vulnerability, desire and fragility, lack and power, control and the flow of time. And this is TK’s land, after all. He discovered his ancestral and iwi connections to the land the hospital rests on not so long ago. So, if Freud imagined a foundational scene of sons killing a father to find their way to a new law, Shortland Street gives this a twist for the era of Land Back: Māori Patriarch against Pākehā Father, in all their rivalry, envy and brotherly love.

Soap opera acknowledges appetite in a way few other dramatic forms do so fully, and Shortland Street’s new writers these seasons push that to ever more dizzying extremes. Religious cults and mass shootings, fires and baptisms, sons and fathers in struggle: excess is the point, and audience desire – for more, more story, more genre, more suffering – drives desire. The well-nigh metafictional turns, from Monique’s stray references to Celebrity Treasure Island through to the chaos of Selina’s media-hungry self-fashioning, display a writing team at full confidence in themselves and their contract with an audience. It’s a dazzling experience.

Stories, we were taught, are supposed to have beginnings, middles, ends. Stories must be somehow distinct to be recognisable as stories and not simply threads sewn in the tapestry of life. Ever since Aristotle’s Poetics this has been a foundation of narrative theory. We read with a sense of an ending. But soaps exist in a kind of perpetual middle.

No one could consume Shortland Street whole, taking each of its plot-lines and making them into something stable and solid. Endings make no sense in a genre that is about perpetual movement. Shakespeare’s line that the valiant ‘never taste of death but once’ could never work in a soap, where repeated tastings are a part of the promise. Shortland Street is seriality all the way down, nothing but an endless repetition of moments in medias res.

It is, in that sense, far closer and more realistically of the logic of our actual lives, in their hurt and surprise and inevitably unsettled endings, than any realist novel, with their contrived conclusions, could ever manage. Sarah, Roimata and Mo, appearing in the Green World between life and death, gestured at that immense seriality on Friday.

The genius of Shortland Street’s writers is that they know what they are doing but also, much more importantly, they want us now to know they know we know they know what they are doing. Taking leave from the one before it, this is a season where narrative is stretched, pulled, turned around and upended. It delights in its own fictionality, and the chance to experiment.

It’s no surprise that Friday’s episode was written by Colleen Maria Lenihan, one of the most exciting new voices in our literature, and a master of the storytelling of grief and loss

One reason for this may be that beginnings, middles and ends are, for all of their conventionality, narrowly Pākehā ways of writing stories and of thinking of them in the world. What if story lives in those moments when, as it does in Patricia Grace’s novel Chappy, "all time becomes present and you understand that you are merely a bead on an unbroken necklace without beginning or end"? Or, in Grace’s most famous book Potiki, the reminder that "a train of stories define our lives, curving out from points on the spiral in ever-widening circles from which neither beginnings nor ends could be defined." What if writers, as Tina Makereti has challenged us to imagine, approached stories speaking with two tongues, working in traditions without end through loops and returns?

It’s no surprise that Friday’s episode was written by Colleen Maria Lenihan, one of the most exciting new voices in our literature, and a master of the storytelling of grief and loss, of Id’s imperious aggressions and haughty needs. Friday’s show was, in the gifted acting of Zak Martin and Ngahuia Piripi as much as in Lenihan’s scripting, a Māori art and a Māori narrative form. That this should be available to us, non-Māori and Māori alike, in prime time, five nights a week, is an ongoing shock and a delight.

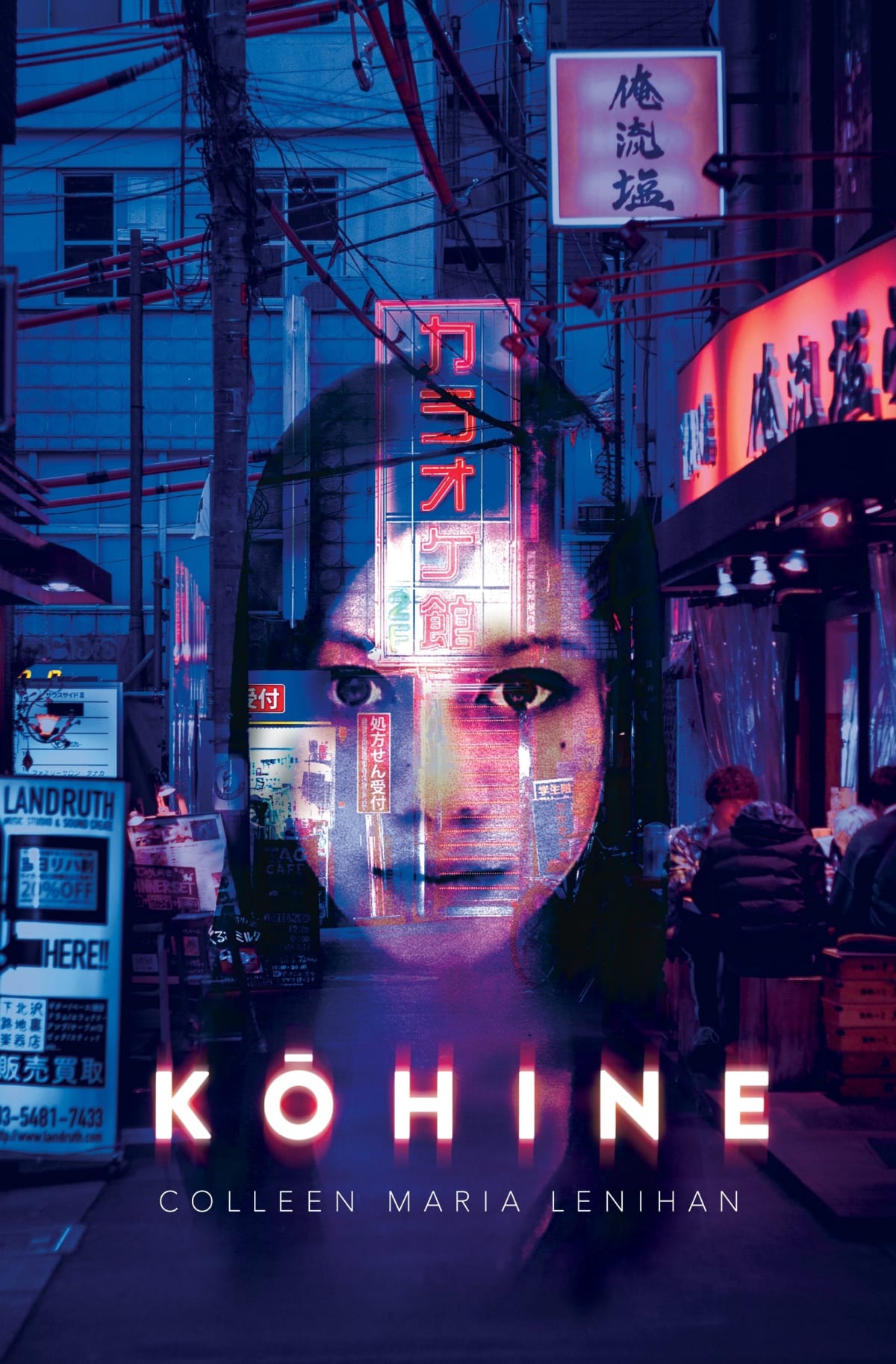

In her short fictions, collected in Kōhine, Lenihan displayed a master’s confidence in smashing the expectations of a form in order to strengthen its vocation. With Shortland Street she has done the same. Her work shaping TK – in all of his swagger and rage, his drives and his responsibility – secures a classic by making it new.

Whatever comes next, and however this story plays from here, Lenihan has gifted something lasting to the culture. She reminds us that, if it has been common to hear this past decade of an age of high television drama, the truth may be that other forms are, finally, catching up to what the soap opera has been managing all along.

The short story collection Kōhine by Colleen Maria Lenihan (Huia, $25) was named one of the best books of 2022 in ReadingRoom, which devoted an entire week to the book and the author.