The two largest agencies responsible for the language we use to discover books in libraries in North America — the Library of Congress in the United States, and Library and Archives Canada — are changing how they refer to Indigenous Peoples.

Recently, the Library of Congress announced that by September 2022 a project would be underway to revise terms that refer to Indigenous Peoples.

Beginning in 2019, Library and Archives Canada made changes within Canadian subject headings, starting with replacing outdated terminology with “Indigenous peoples” and “First Nations,” and adding terms that specify Métis and other specific nations and peoples.

It is important to acknowledge what these library changes can and cannot do, and the need for consultation with and guidance from Indigenous communities and Indigenous library workers. This is a departure from business as usual for maintaining these systems.

Library indexing

Both Library of Congress and Library and Archives Canada manage the term lists used in public and academic libraries throughout both countries.

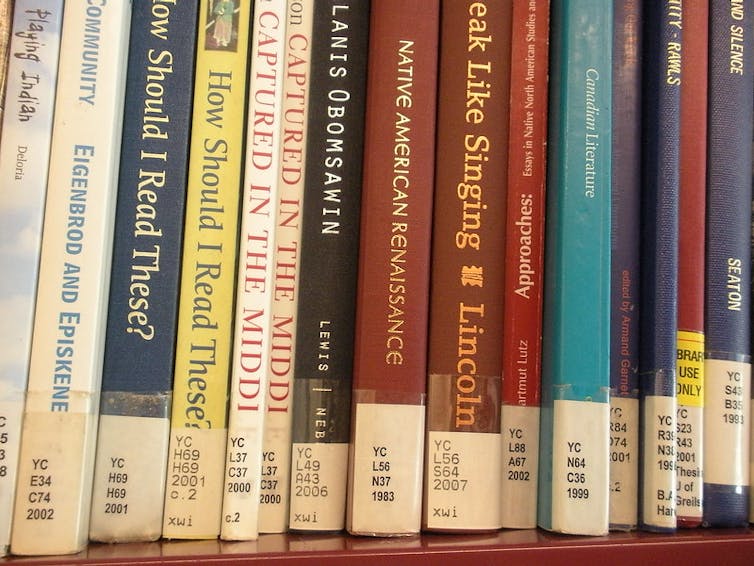

When a book is published, library workers use lists of approved terms to indicate the subject or topic of the book. These terms determine how the book can be found in a library search and may even be printed on the copyright page of the book itself. The catalogue record then gets copied to each library that holds a copy of the book.

Read more: Libraries can have 3-D printers but they are still about books

Outdated terminology such as “Indians of North America” has remained in these term lists despite changing use in society and no longer matches the language used in the books themselves. The management of these terms lists last made international news when politicians interfered in a change from “illegal aliens” to “undocumented immigrants.”

Revisions to systems

The heading “Indians of North America” has been part of these lists since the Library of Congress Subject Headings were first standardized and shared with libraries more than a century ago.

Library researchers and librarians hope revisions to existing systems will reduce some of the friction of using the library for Indigenous and decolonizing research. This friction relates both to materials being categorized strangely, and how the use of older terms like “Indians of North America” could negatively affect some members of Indigenous communities, even while there are a diversity of views that exist in Indigenous communities about identity labels.

1,000 terms under review

Since 2015, the Manitoba Archival Information Network has shared a list of more than 1,000 terms relating to Indigenous Peoples with suggestions for more accurate and respectful language. Many of the recommended changes use the term “Indigenous peoples,” which exists in the term lists already.

Right now, adding a geographic term to the end, as in “Indigenous peoples — Asia” is a permitted heading, except in the case of the Americas. At present, terms like “Indigenous peoples — United States” and “First Nations (North America)” redirect to “Indians of North America.”

The same is the case for terms that redirect to “Indians of South America.”

Library and Archives Canada continues to roll out changes like a shift from “Canadian poetry (English)–Inuit authors” to “Inuit poetry (English).”

Indigenous knowledge organization

Beyond revamping misleading terminology, library science scholars and Indigenous knowledge holders (like Sandy Littletree, with colleagues) are examining how to advance Indigenous knowledge organization practices in library systems.

Research conducted by my team of librarians and students shows that authors prefer their books to be labelled in Indigenous-centered approaches or reconciliation approaches. For example, Xwi7xwa Library is a branch of University of British Columbia’s academic library entirely dedicated to Indigenous materials. Indexing is adapted from a system developed by Kahnawake librarian Brian Deer in the ‘70s for the National Indian Brotherhood, now the Assembly of First Nations.

The the Greater Victoria Public Library has introduced locally developed interim Indigenous subject headings that use more current terminology.

Interviews with authors

Over the past two years, my team and I interviewed 38 authors whose books were labelled in libraries with terms like “Indians of North America.”

Those authors told us these terms didn’t match the language in their books, nor what is acceptable in their professional communities. They shared how these terms created difficulty in findings works by or about Indigenous Peoples.

They explained how people using library search functions would have to use terms they disagreed with and wouldn’t use in their classes and writing. Ambiguous terms like “Indian cooking” and “Indian activism” create confusion as to whether an item pertains to Indigenous Peoples in North America or India.

As authors in our study suggested, the continued use of these terms imposes a colonial worldview on books that are often resisting, challenging or exposing the harms of colonialism.

Slow to change

Library systems tend to be slow to change because they prioritize consistency. Yet the Canadian and American systems undergo constant revision to add new terms and, less often, to replace old terms.

Since there are more than 1,000 terms relating to Indigenous Peoples in library lists, revisions to this topic will be monumental. In a typical month, around 200 new headings are added to the Library of Congress Subject Headings, across all topics.

Terminology for Indigenous Peoples from this continent varies as communities themselves are numerous and diverse. At the same time, terms like “Indians” persist in law in Canada and the United States.

Colonial borders

Changes of these terms, through consultation with and guidance from Indigenous communities and Indigenous library workers, can bring our library systems into alignment with language used in common conversation and academic research.

They cannot invalidate the terms that people use to refer to themselves. A library term list is for shared, government-supported systems to enable discovery and access and does not determine self-expression.

Even in that context, changing terms for Indigenous Peoples is unlikely to change the awkwardness of how these lists currently use Canadian and American colonial borders. For the time being, works about Coast Salish botany or art, for example, may still end up labelled redundantly with “Indigenous peoples — British Columbia” and “Indigenous peoples — Washington (State).”

Continued research will be needed as libraries consider how to update their practices.

Julia Bullard receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.