From Mahendra v. Winslow, decided today by Judge James Lorenz (S.D. Cal.):

Plaintiff is a medical doctor and works as an OB/GYN. {For purposes of this order, the Court accepts as true Plaintiff's factual allegations.} Plaintiff provided medical services to patients at the Irwin County Detention Center ("ICDC").

In September 2020, a nonprofit organization sent a letter to the Department of Homeland Security related to reports about high rates of hysterectomies at ICDC. The letter also expressed concern over COVID-19 measures. Plaintiff was not identified in the letter. The organization then shared the letter with several media outlets. In late September, there were various stories on Plaintiff related to medical procedures at ICDC.

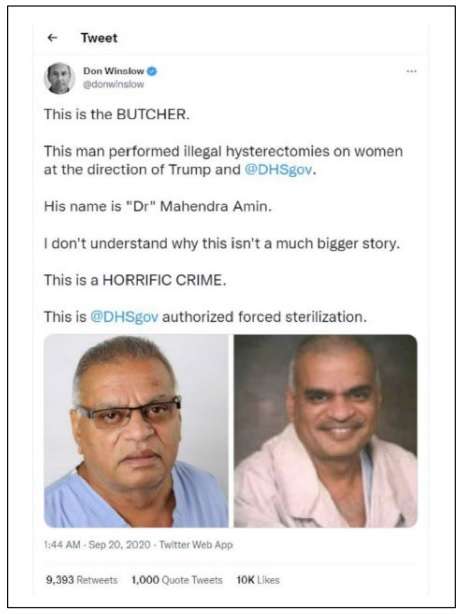

On September 20, 2020, Defendant Don Winslow—a New York Times bestselling author—published statements on his Twitter account about Plaintiff:

Defendant has over 600,000 followers on Twitter.

Plaintiff contends the statements are false. Plaintiff alleges he only performed two hysterectomies on patients at ICDC and the procedures were medically necessary. The patients provided their informed consent to the procedures. Moreover, the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement approved the procedures after it conducted an independent review of the treatment, including review from a nurse and an independent doctor. That review process takes about two weeks.

Five days before the Contested Tweet, it was revealed that the allegations about Plaintiff were not based on first-hand accounts, and ICDC (in addition to the hospital) confirmed Plaintiff only performed two hysterectomies on ICDC patients.

Plaintiff sued for libel, and the court allowed the claim to go forward. It concluded plaintiff wasn't a public official and thus didn't have to prove "actual malice":

Here, Plaintiff worked as a contractor at ICDC. He provided medical treatment after receiving informed consent from the detainees and approval from the Department of Homeland Security, which required review from a nurse and an independent doctor. There are no allegations to show Plaintiff had "substantial responsibility for or control over the conduct of governmental affairs," including control over the detainees or official policies (e.g., what treatments detainees were able to receive). There is also nothing in the pleadings to suggest Plaintiff enjoyed "significantly greater access to the channels of effective communication and hence [had] a more realistic opportunity to counteract false statements than private individuals normally enjoy." ….

The court held the plaintiff adequately alleged a statement of fact rather than opinion:

Defendant, in the Contested Tweet, asserted an objective fact: Plaintiff committed a crime. More specifically, Plaintiff "performed illegal hysterectomies" on women in detention centers and engaged in "forced sterilization." The arguably hyperbolic language in the Contested Tweet, "This is the BUTCHER," does not negate the assertion of fact. That language simply corresponds with the statement that Plaintiff performed illegal surgeries on detainees. This assertion may be proved true or false.

Defendant argues the Court should consider his earlier tweets. It is reasonable to infer the Contested Tweet, when appearing on Twitter users' feeds, would not have been presented at the same time as Defendant's earlier tweets. Therefore, even if it would be appropriate to consider the other tweets (which are not in the complaint or relied upon in it), they would not alter the above analysis at this stage. See Restatement Second of Torts, § 563(d) ("the context of a defamatory imputation includes all parts of the communication that are ordinarily heard or read with it."); Underwager v. Channel 9 Austl. (9th Cir. 1995) ("to determine whether a statement implies a factual assertion, we examine the totality of the circumstances in which it was made. First, we look at the statement in its broad context, which includes the general tenor of the entire work, the subject of the statements, the setting, and the format of the work."); Franklin v. Dynamic Details, Inc. (2004) ("courts look at the nature and full content of the communication and to the knowledge and understanding of the audience to whom the publication is directed.")

Defendant also relies on the assertion that his followers would have known any tweet of his was simply an opinion. But it is unclear from the record that only Defendant's followers saw the Contested Tweet. It is reasonable to infer, which the Court must do in Plaintiff's favor, that non-followers saw the Contested Tweet in their feed, based on the more than 9,000 retweets of the Contested Tweet.

Further, Defendant argues Twitter is known as a forum for expressing opinions about controversial issues, and therefore any reader would know Defendant's statements were only an opinion. This argument is rejected because it is reasonable to infer that, in addition to opinions, Twitter users may tweet verifiable, objective facts. Lastly, Defendant cites the heated public debate over immigration policy and treatment of detainees that was occurring when he posted the Contested Tweet. But that context does not alter Defendant's assertion of fact as to Plaintiff's criminal conduct.

And the court concluded that the tweet wasn't protected under the California statutory fair report privilege, which exempts from libel liability "a fair and true report in, or a communication to, a public journal … of [a] public official proceeding":

Based on the limited record, the Court is not persuaded Twitter reasonably fits within the term "public journal." Merriam-Webster defines "journal" as "a daily newspaper or a periodical dealing especially with matters of current interest." Twitter is a micro-blogging platform, not a newspaper or periodical. Regardless, the Contested Tweet does not discuss or cite any official proceeding. Instead, the statements concern Plaintiff's alleged conduct as a doctor at detention centers. Although Defendant contends other posts on Twitter referred to investigations, those posts are separate from the one at issue here. Based on the allegations, the privilege is not applicable.

Note that California's fair report privilege seems unusual in its limitation to a "report in, or a communication to, a public journal"; the Restatement (Second) of Torts § 611, which generally summarizes the common law, has no such limitation. Under the California statutory test, as interpreted by the court, Tweeting out a quote reporting what a witness said in a trial (or perhaps even what a court said a witness said in a trial) might well be libelous, under the Republication Rule; that strikes me as wrong. Perhaps some future case might consider whether the First Amendment mandates a stronger fair report privilege, applicable equally to people who aren't writing for or to "public journals." See Trainor v. The Standard Times (R.I. 2007) ("Although we need not and do not pass upon the issue in this case, we note that recognition of the fair report privilege may quite possibly be constitutionally required in light of the courts' continually evolving understanding of the implications of the First Amendment."); Liberty Lobby, Inc. v. Dow Jones & Co., Inc. (D.C. Cir. 1988) ("Federal constitutional concerns are implicated … when common law liability is asserted against a defendant for an accurate account of judicial proceedings."); Medico v. Time, Inc. (3d Cir. 1981) ("Although the Supreme Court has never explicitly recognized a constitutional privilege of fair report, several of its recent decisions point toward that result.")

Congratulations to plaintiff's counsel, Wynter Deagle, Anne-Marie Dao, and Yarazel Mejorado of Sheppard Mullin; Stacey Godfrey Evans, Tiffany Watkins, and John Amble Johnson of Stacey Evans Law; and Scott Grubman.

The post Libel Lawsuit Over Tweet by Prominent Novelist Don Winslow Can Go Forward appeared first on Reason.com.

.png?w=600)