The 2026 Census presented a crucial opportunity to count the LGBTQI+ population in Australia for the first time.

Instead, the Albanese government has opted to disregard important questions on gender and sexual identity. Once again, LGBTQI+ Australians will be invisible in population data, sparking outrage in the community.

Serious concerns were raised about the 2021 Census and its failure to ask questions about sexual orientation and gender identity. This included complaints to the Australian Human Rights Commission on the basis that the survey failed “to ask meaningful questions to properly count members of the LGBTIQA+ community”.

Following the backlash at the time, the Labor government pledged to gather relevant data in the upcoming 2026 Census. Yet, this has been abandoned. The Sex Discrimination Commissioner has now called for the government to reverse the call.

This decision has huge implications for public policy, but also leaves LGBTQI+ people feeling unheard and unseen.

Previous question problems

In 2021, the census limited the ability for LGBTQI+ people to be counted and considered. This included in data collection, analysis and distribution of the findings.

For example, despite giving respondents the option to select “non-binary sex”, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) abandoned these data. They said “the sex question did not yield meaningful data”.

This seemingly “garbage data” was inevitable because the term “non-binary” is far more commonly associated with gender identity, rather than sex, leading many to be unsure exactly what was being asked.

For the 43,220 people who exclusively selected non-binary sex, they were reorganised into male/female binary using “random allocation”.

Where an individual provided a male or female response alongside a non-binary sex response, the binary male/female response took precedence.

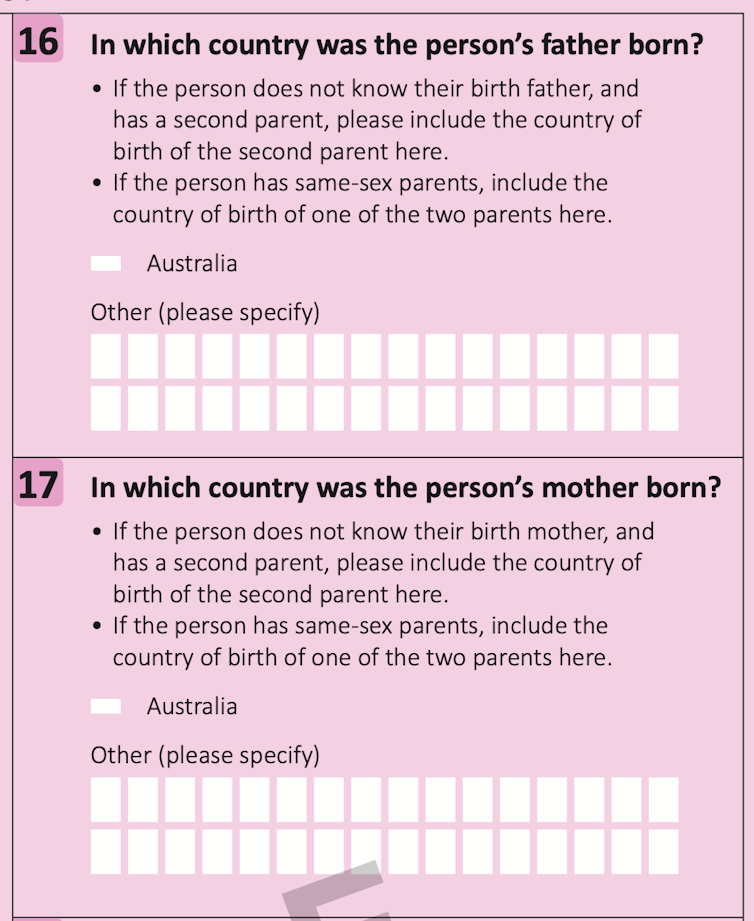

This “straight washing” of data also occurred in the design of the census forms. Respondents were asked “in which country was the person’s father born?” and “in which country was the person’s mother born?”.

Given the gendered language used in these questions, sufficient data is unable to be produced to specifically identify individuals with same-sex parents, leading many rainbow families to feel as though their presence had been erased.

There are also no specific questions included in the census designed to record sexual orientation, despite at least two government departments being on record at the time professing a need for such data to deliver appropriate and tailored services.

This decision to continue running the 2026 Census as is, without questions on gender identity and sexuality, have also been criticised by some crossbenchers. Independent MP Allegra Spender said the lack of data makes it “impossible to make policy for the LGBTQ+ community”.

The right to be counted

One line of argument that has emerged since the announcement about the 2026 Census is that the government simply dosn’t need to know about the sexuality of its people. This undermines the crucial role the census plays.

The United Nations advises that census data has a global impact. It contributes to:

funding allocation

urban planning

public health

infrastructure development

evidence-based policy formulation.

Census data has a concrete impact on the livelihood of Australians, contributing to social and economic policy. Decisions about transport, education and health, for example, can be derived from the data we gather in the census.

However, others have reminded us that without this critical information, we don’t know very basic things about our population.

As it stands, we don’t know how many people identify as LGBTIQ+ in Australia. We don’t know where they live or anything about their health, families and socioeconomic status, to name but a few.

What we do know is LGBTQI+ people are at higher risk of mental ill health and suicide and domestic violence. To craft policy responses to fix these things, we need more data.

In lieu of good quality information, decisions made about the LGBTQI+ community are uninformed at best. At worst, LGBTQI+ people are completely ignored.

Ignoring calls for change

The government remained silent on its decision for days.

This week, Deputy Prime Minister Richard Marles said:

we don’t want to open up a divisive debate in relation to this issue […] We’ve seen how divisive debates have played out across our country and the last thing we want to do is inflict that debate on a sector of our community right now.

The decision is clearly being framed as a measure to protect LGBTQI+ people from backlash.

Yet, omitting these questions goes against demands from many LGBTQI+ community organisations, such as Equality Australia, which has gathered roughly 16,000 signatures in their #CountUsIn2026 campaign.

Excluding LGBTQI+ people from the census also goes against the Bureau of Statistics’ best practice standards on collecting data on sex, gender, variations of sex characteristics and sexual orientation.

These standards were designed to be used by government bodies, academics and private organisations in their own “statistical collections to improve the comparability and quality of data”. According to the ABS, researchers should follow the standard for planning, implementing, monitoring and evaluating policies and programs.

The governments’ decision to abandon the LGBTQI+ community under the guise of “protection” goes against these guidelines, as well as requests from governmental organisations, activists and the LGBTQI+ community at large.

It will also likely embolden those who wish to further marginalise LGBTQI+ people and see them excluded from Australian life.

The census doesn’t just inform us about individuals, but tells us which groups the government wishes include and exclude from the population.

Leaving the 2026 Census unchanged sends a message to LGBTQI+ people that they don’t matter in the eyes of the state.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.