Leo Frobenius was a largely self-taught German ethnologist (someone who studies societies and cultures) who undertook numerous expeditions. One of them, from 1928 to 1930, was to southern Africa, where he recorded the rock art of the San people (indigenous hunter-gatherers and their descendants).

In the past few years there has been a revival in South Africa of interest in his legacy. This follows archival work and museum exhibitions in South Africa and several prominent exhibitions internationally.

His expedition to southern Africa was to document and copy local rock art. The expedition’s artists Elisabeth Mannsfeld, Maria Weyersberg, Agnes Schulz and Joachim Lutz made the copies, which were housed in various museums.

Commendably, Frobenius brought African art to the attention of people in the culturally western world (or global north). This influenced European artists such as Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró and Paul Klee. In raising the western profile of African rock art as something noteworthy and interesting, Frobenius built on the earlier efforts of the little-known South African teacher and rock art copyist Helen Tongue. An exhibition of her copies of San rock art in London in 1908 challenged the opinion that San rock art was “primitive”.

Recent media articles in South Africa have raised questions about Frobenius’s work – including why it “does not have much of a profile in South African rock art circles”.

This is true. Professional rock art researchers see flaws in Frobenius’ thinking and inadequacies in the copies created during his expedition.

Afrikaner nationalists and Nazis

Although the point is sometimes acknowledged in passing, it’s worth stating in no uncertain terms that Frobenius and his expeditions are tainted by association with cultural anthropological ideas that influenced Nazis in Germany and Afrikaner nationalists in South Africa.

DF Malan, who would become the first prime minister of apartheid South Africa, funded the like-minded Frobenius. Malan chose to fund him rather than the South African-born ethnographer and rock art researcher Dorothea Bleek. Her liberal, local efforts to publish the copies of rock art produced by the geologist and ethnologist George William Stow were deliberately passed over.

Frobenius thought that groups of people who shared inherited traditions were closed. This racist view saw cultures as largely unchanging. It attributed any changes that did occur to more “advanced” cultures.

Among his critics is the Nigerian writer and Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka, who points out that Frobenius thought the Nigerian Yoruba people had “degenerated” from an imagined, highly civilised “Atlantis” – a process he shockingly called “negrification”. To Frobenius, African achievements were the influence of foreign cultures:

Europe brings up to the surface what sank down with Atlantis.

Inaccurate copies

Unfortunately, the Frobenius copies, as interesting as they are, are unsuitable for anything other than art-historical research or museum exhibitions.

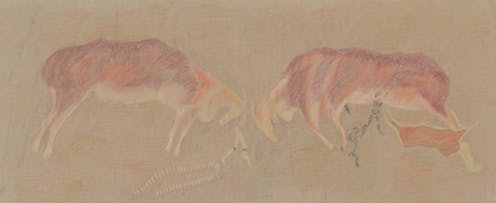

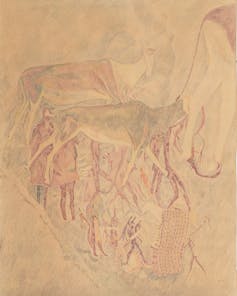

For one thing, the artists’ use of various media (watercolours, pencil crayons and black ink) produced mixed results. Impressionist pencil crayon copies sometimes misrepresented actual shapes, textures and colour patterns (Figure 1). Watercolours could reproduce the fine lines and solid colours seen in the rock paintings (Figure 2).

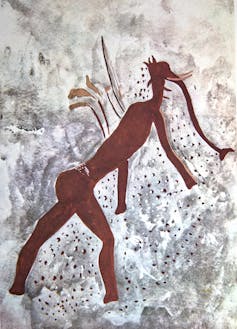

Compare, for example, the Frobenius copy of the “elephant-man” (Figure 2, now in the KwaZulu-Natal Museum) to a photograph (Figure 3, which appears in the second edition of Frobenius’s book).

The copy also differs significantly from the digital tracing by rock art researcher Jeremy Hollmann (Figure 4), and the detailed inked tracing (Figure 5) produced by the meticulous draughtsman and copyist Harald Pager.

More important than how the copies were made is that the Frobenius copyists did not understand the rock art. For example, we now know that the figure is a human partially transformed by elephant potency and that it is surrounded by bees (another San metaphor for potency). We also know that the string of triangular heart-like shapes emanating from the figure’s groin is a feature found repeatedly in San rock paintings.

Then and now

The question of accuracy brings us to an important distinction between western art history and anthropological archaeology. Art history deals with the aesthetic aspects of the images, their history and influence on other image-makers. The approach remains largely descriptive in terms of features derived from the copyists’ or viewers’ own, often culturally western, background.

By contrast, anthropological archaeologists seek to explain the imagery in terms of the image-makers’ beliefs, not their own. South African rock art researchers, including the authors of this article try by various means, especially recourse to San beliefs and long and profound familiarity with a wide range of rock art images, to decipher their meaning.

It’s interesting that Frobenius wrote of San rock art as being “shamanistic”. It is indeed, but Frobenius did not come to this conclusion via an intimate knowledge of San ethnography. He argued that San images, like those painted on the drums of Siberian shamans, perhaps represented the spirit world. Frobenius was right for the wrong reasons: similar “primitive cultures”, he thought, made and used images in similar ways.

Today, the Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd Collection is famous. Compiled by these two researchers in the 1870s, this collection is preserved in the Jagger Library at the University of Cape Town. Its value lies in its 12,000 manuscript pages of verbatim San text in the no-longer-spoken ǀXam language with line-by-line English translations.

It contains comments on copies of San rock art which may be followed in themes that run through the other manuscript pages to build a picture of what the San themselves believed was represented. In this way, and drawing on other sources of San belief, researchers formulate informed interpretations.

Ultimately, the difference between the Frobenius copies and the images produced today by anthropological archaeologists is a simple one: whereas Frobenius’s artists did their best to reproduce “unfamiliar imagery”, anthropological archaeologists endeavour to understand it through ever-increasing familiarity with the San idiom. Ethnographic sources help comprehend and perceive San rock art, not from the ill-fitting western gaze, but as the artists themselves would have done.

David M. Witelson is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of the Witwatersrand's Rock Art Research Institute.

Sam Challis receives funding from the National Research Foundation African Origins Platform (Grant no. AOP117735).

David Lewis-Williams and Paul den Hoed do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.