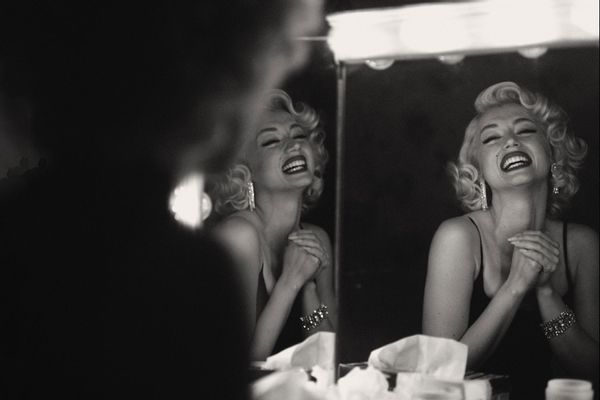

With the release of Andrew Dominik's controversial film "Blonde," an adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates' equally controversial novel fictionalizing the life of Marilyn Monroe, there's been an impassioned cultural outcry against what many people see as the reduction of Marilyn to pure victimhood. Never one to shy away from merrily dumping kerosene all over discourse and lighting her match, writer-director-cringe Tweeter Lena Dunham penned an essay for Vogue titled, "What Marilyn Monroe Means to Me." Unsurprisingly, the essay is more about what it means to be Lena Dunham at 36, the age Marilyn Monroe was when she died (though Dunham does take pains to remind readers that she is, in fact, "36 and a half").

Unlike Marilyn Monroe, I'm able to defend myself against Dunham's destructive, essentialist take on infertility and self-worth.

The only direct point in common for both women is severe endometriosis: The disease supposedly contributed to Monroe's difficulties conceiving and sustaining a pregnancy, and it compelled Dunham to get a hysterectomy for relief from years of debilitating pain. One might imagine that shared infertility would inspire loud and proud feminist Dunham — whose new Amazon film adaptation of "Catherine, Called Birdy" is receiving roundly positive reviews for its poppy, girl-power bent — to reclaim Monroe from the stereotype of the tragic barren woman. One would be wrong. Dunham is breathtakingly cruel about Monroe's infertility, offering the mean-spirited assertion that, "without her wished-for baby, Marilyn was just another lonely starlet with a few broken marriages under her belt . . . and a raft of people she paid to look out for her interests but continued to treat her as a disposable resource."

Taking it upon herself to imagine Monroe's inner anguish as "the most discussed woman in the world, both valued and cursed for your feminine power" who is "not . . . able to do what we think women should do," Dunham describes infertility as a contributor in the doomed beauty's decision to "roll over, say 'Fuck it,' and go back to sleep." An image she juxtaposes with Monroe's actual deathbed. Dunham's writing about infertility is swaddled in self-pity that she projects upon the bodies of any woman who can't have a biological child, like Marilyn — and like me. But unlike Marilyn Monroe, I'm able to defend myself against Dunham's destructive, essentialist take on infertility and self-worth.

Equating womanhood with carrying children isn't just wrong, it's profoundly dangerous.

Unable to knuckle through cramps that compelled me to learn Lamaze breathing and heavy bleeding that leeched the life force out of me, I opted for a hysterectomy. As I researched the procedure, searching for what my recovery might entail and what life could look like once my scars healed, I mostly found images of gray-haired women staring pensively over tea or advice for husbands and grown children who want to be supportive during "the change of life." Most of my friends were still young enough to become first-time parents and making the choice to never join them in the experience of watching a belly swell or feeling a flutter inside me — even if it was the right choice, the only choice against crushing pain and fatigue — made me feel old and alone.

Dunham's 2018 essay was one of the only hysterectomy stories from a woman under 40. Even if I rolled my eyes at the cringier scenes — like the men on the set of "Girls'" final season regarding her, clad in her character's fake baby bump, as some sacred vessel figure — I searched for some sense of kinship. Though I've never found Dunham compelling as "a voice of a generation," I related to her desperation to wrench herself out of that razor-wire ouroboros of pain that birth control and yoga and acupuncture and herbs couldn't touch: "I gave up on more treatment. I gave up on more pain. I gave up on more uncertainty."

Despite having a platform to address all aspects of life post-surgery, Dunham's post-hysterectomy output traffics in crassly maudlin sentiment about infertility, making it a crucible of personal brokenness. Over countless interviews and Instagram — including a nude shoot symbolically taken nine months post-surgery and even a feature film called "Sharp Stick," about a young woman after an early-in-life hysterectomy — Dunham ties her value to the organ she's lost, writing on Instagram that medical infertility brought "feelings that my worth and purpose were being taken from me." Even in her initial Vogue essay, she randomly observes that, "women are attached to their uteruses (for me, an almost blind, delusional loyalty, like I'd have to a bad boyfriend)."

One wonders who, exactly, Dunham is referring to by this monolithic word, "women"? Certainly not the people posting on Reddit forums and sites like Hyster Sisters happily counting down to "yeeterus" days and celebrating with special hysterectomy cakes and cookies frosted with slogans like, "Goodbye uterus, you were cramping my style," "Monthly subscription: canceled," and my personal favorite, "see you later, ovulator." Her essay "about" Monroe goes even further in dressing up gender essentialism in the sackcloth of personal grief: "Losing your fertility has a way of forcing questions about your womanhood — I spent a good two years asking myself what my purpose was . . ."

These words seem more suited to Ben "WAP sounds a like medical condition" Shapiro or any TikTok tradwife than a star who built her brand as an avatar of intellectually frothy, artisanal white millennial feminism. When fascistic forces across government and media have turned, "What is a woman?" into their scaremongering "gotcha" question du jour, holding its supposed answer like a knife to the throats of transgender people, equating womanhood with carrying children isn't just wrong, it's profoundly dangerous.

Though I never wanted a biological child with the same intensity she claims, watching a door click shut forever made me wonder what is on the other side of it. Leading up to surgery, my desperation to hold a thought in my head or sleep through the night overtook any concerns about my fertility. Only months post-op, as my hormones began to settle and I started re-gaining strength, did I seek out my pathology report. Clinical descriptions of fallopian tubes so laden with endometriosis that they warped in on themselves, a uterus bogged down with fibroids and polyps so large that it had to be peeled off my bladder overwhelmed me.

Dunham is entitled to her sorrow, but she is not entitled to a grand, unified thesis on infertility.

On the phone with a friend, I wept. Perhaps even hysterectomy hadn't made me infertile; my body had made its choice for me long before that morning I counted down from 10. Whatever fantasies I might have harbored about being liberated from my avowed spinsterhood, complete with "late in life" baby were already gone before I could fully acknowledge them. My infertility is like an old injury that bothers me on rainy days; a lingering soreness that makes me extra careful with myself, avoiding certain friends' Instagram feeds or steering clear of the baby clothes section of Target. Sometimes, something hard hits a tender spot, and a podcast ad with a small child chatting happily to his mother makes me cry. I may come away from these moments bruised, but I'm not broken.

The path of my life is so much broader than the road not taken. My purpose came to me after surgery and complete medical infertility; without the constant glaze of pain, I'm a more present friend. I swim. I sit through long movies, no anguished trips to the bathroom. I pick up old hobbies. Every day into recovery, even the hard days, I feel a brightness click behind my eyes. That brightness is my worth — the light of possibility filling the space where the dark star of my uterus had been.

Dunham is entitled to her sorrow, but she is not entitled to a grand, unified thesis on infertility. In her recent Vogue essay, she laments infertility as "a humiliation more ancient than any I had known," a turn of phrase that simultaneously signifies nothing while portraying herself, and Marilyn, and me — anyone who will never have a baby — as little more than the victim of some cosmic joke. Like Dunham, I chose to free myself from annihilating pain, even if that freedom came with the absolute inability to ever bear a child. But my worth and purpose were not lifted out of me by a surgeon's hands. Neither was my womanhood.

I am not disposable, or humiliated. There is purpose and potential beating through my veins right now, and it matters more than what could or could not have grown inside of me.