Classic film cameras are enjoying a revival, so what about a classic digital camera? For starters, is there such a thing? And, secondly, why would you bother when the current tech is so good? Well, if anything, the design of contemporary digital cameras has become quite conventional compared to the early days, so there is some fun to be had with models from the days when everybody was still feeling their way around. And, given nobody has really been taking much notice of older digital cameras, they can be very cheap indeed. The Leica Digilux 3 that we’ve chosen for our first classic digital camera test cost $2,500/£1,880/AU$4,300 when it was new back in 2006 (although it was definitely overpriced) and now you can pick one up for around £

$250/£200/AU$650 for the body only, or the region of $600/£450/AU$1,100 with its standard lens. That these aren’t exactly garage sale prices indicates this model still has some appeal nearly 17 years after it was launched. The Leica badge will certainly have something to do with this – even though the Digilux 3 was built in Japan by Panasonic – but there’s more to it than that… in reality, as you’ll see, this is still a very usable camera.

Check current offers on the Digilux 3 on eBay.com or on eBay.co.uk

So, is it worth taking a punt on a pre-loved digital camera? Well, the answer now is a qualified ‘yes’. As digital camera technology was going through its main growth spurt, superseded models were pretty much immediately obsolete, especially in terms of resolution. Now that maturity has been reached, the performance-related developments are less dramatic and the do-I-really-need-it test comes into play. This is certainly true of the super-fast shooting speeds now made possible by the mirrorless configuration and, if you’re a stills purist, then video remains a functionality you don’t really want… although it’s unavoidable these days.

Consequently, there are probably two major considerations when thinking about buying an older digital camera – resolution and recording media. In terms of the former, we reckon that around eight megapixels is the acceptable minimum res these days, assuming that you’d still like to be able to make decent-sized prints… well, at least up to the classic 8x10-inch. At a print resolution of 300dpi, you need around 7.2MP, so the 7.5MP Digilux 3 scrapes in here.

There were a number of memory card formats before we arrived at the near-universal SecureDigital (SD) format in 1999. So, for example, the SmartMedia card, which was favored by both Fujifilm and Olympus early on, has been obsolete since 2006. So if you particularly wanted one of these cameras, it would need to come with a card or you’d need to source one secondhand.

Likewise, the xD Picture Card format that followed it in 2002 that was jointly developed by Fujifilm and Olympus, but discontinued in 2009. While the earlier SD card cameras won’t support many later versions of the format – most notably SDXC which has a different contact configuration – at least you can still buy the original SD and SDHC variants, and quite cheaply too. With many DSLR users now transitioning to mirrorless cameras, there’s a growing supply of secondhand models and anything that’s five to 10 years old is likely to be a safe bet – although the younger the better – with the usual caveats regarding the overall wear and tear, pixel dropouts and the number of shutter activations.

Buying secondhand will allow you to step up a level or two, and so your budget may well stretch to a semi-pro full-frame model such as the Canon EOS 5D Mark III or the Nikon D800 with the advantage that models such as these were built to work. Consequently, they potentially may still have plenty of life left in them for you, and the standard feature sets – at least as far as stills photography is concerned – haven’t changed significantly, with the resolutions in the region of 20+ MP, which is more than adequate for a whole lot of applications.

Out of the mainstream

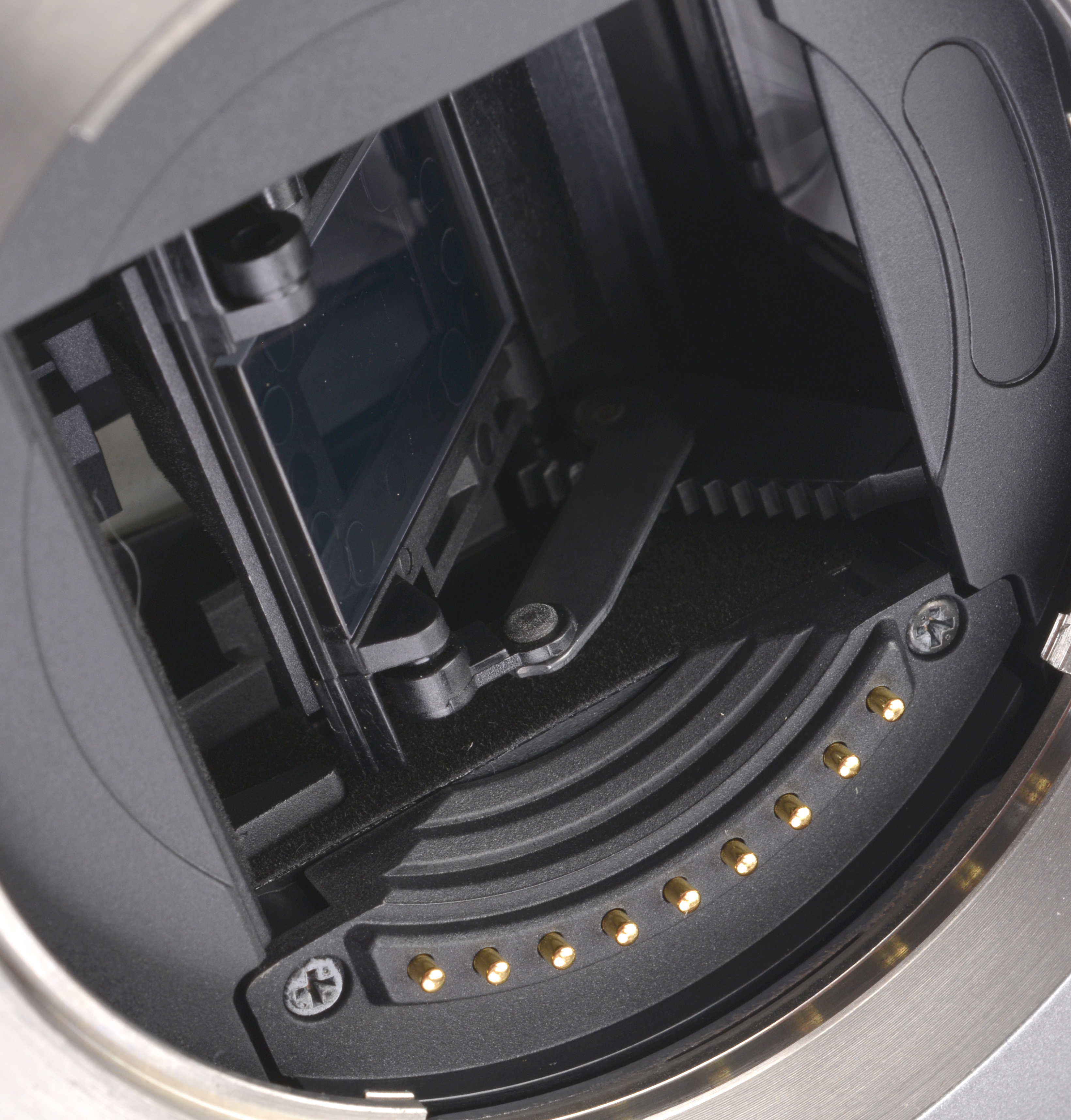

So what about going even older and less mainstream? Let’s see how our pre-loved Leica Digilux 3 stacks up against what we’ve come to expect from a higher-end digital camera… and even take for granted nowadays. Despite the way it looks, the Digilux 3 is also a DSLR and uses the Four Thirds Standard sensor size and lens mount fitting. It’s derived from the Olympus E-330, which also spawned the Panasonic Lumix L1 that’s the close cousin of the Digilux 3. All three employ a viewfinder assembly turned on its side, including the reflex mirror that flips to the left rather than up.

Olympus devised this arrangement – which it first used on the Pen F half-frame cameras in the 1960s – to allow for a separate sensor and image processor to deliver a live view stream to the monitor without hindering normal reflex viewing. Panasonic chose to adopt a simpler mirror lock-up procedure for obtaining a live view on the L1, but it kept the ‘side-on’ TTL optical finder. The Digilux 3 has the same arrangement, which means the external appearance is more rangefinder than SLR. Incidentally, the styling is by the legendary German designer Professor Achim Heine who also penned the C1, C2 and C3 compacts, the CM and CM Zoom, the D-Lux 1, the Digilux 1 (which had a fixed lens), various binoculars and, more recently, the Leica L1 and L2 luxury watches.

Live view was still a new feature in 2006 and the fixed monitor’s low resolution – just 207,000 pixels – is an immediate reminder of the Digilux 3’s vintage. It’s actually not as dreadful as you might expect and the color reproduction is pretty good, but the limited dynamic range means it really struggles in contrasty situations. The optical finder

is on the small side and initially feels a bit cramped, but it’s bright enough and, over time, feels quite comfortable to use. As per most DSLRs, the autofocusing sensor module is located in the mirror box and normally receives light from the subject via a sub-mirror. With the mirror locked up, this obviously isn’t possible, so autofocusing with live view involves the cumbersome process of the reflex mirror flipping back into the light path to facilitate distance measurement and then locking up again

(well, it actually locks to the left, but you know what we mean). At the same time, the shutter closes and then reopens to allow for live viewing. To complete the exposure, the mirror cycles right-left-right-left and the shutter cycles close-open-close-open, which is accompanied by plenty of whirring and clunking. No wonder Panasonic thought that there had to be a better way. It didn’t really do much with DSLRs and only one other model, the L10, followed the L1 in August 2007. Exactly a year later, in August 2008, Panasonic launched the mirrorless Lumix G1 and started a revolution in interchangeable lens cameras.

The Digilux 3’s AF only has three measuring points located in the centre of the frame – a central cross-type array flanked by two horizontal arrays – so it’s crude by today’s standards and, in fact, was already a bit behind the times when the camera was new. Nevertheless, it works well enough in terms of speed and overall reliability, but obviously is very limited in its effective area. Manual focusing is arguably the better bet in many situations, especially as there’s a magnified MF Assist function in live view which can be set to 4x or 10x.

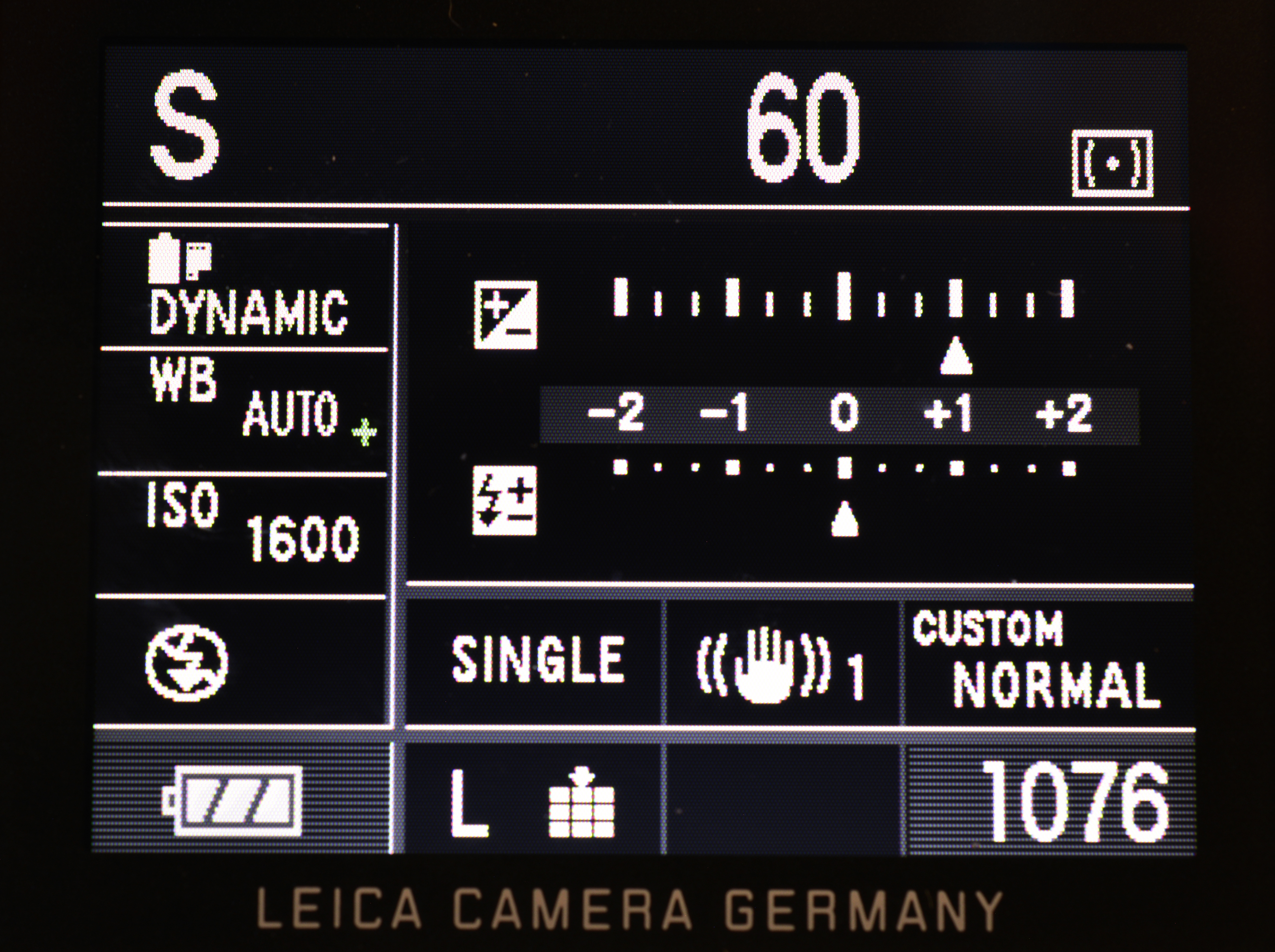

The live view screen can be configured with a grid guide (including the classic 3x3) and a ‘real time’ histogram, plus it’s possible to switch the framing between the three image aspect ratios that are available, namely 4:3, 3:2 and 16:9.

The Leica 'look'

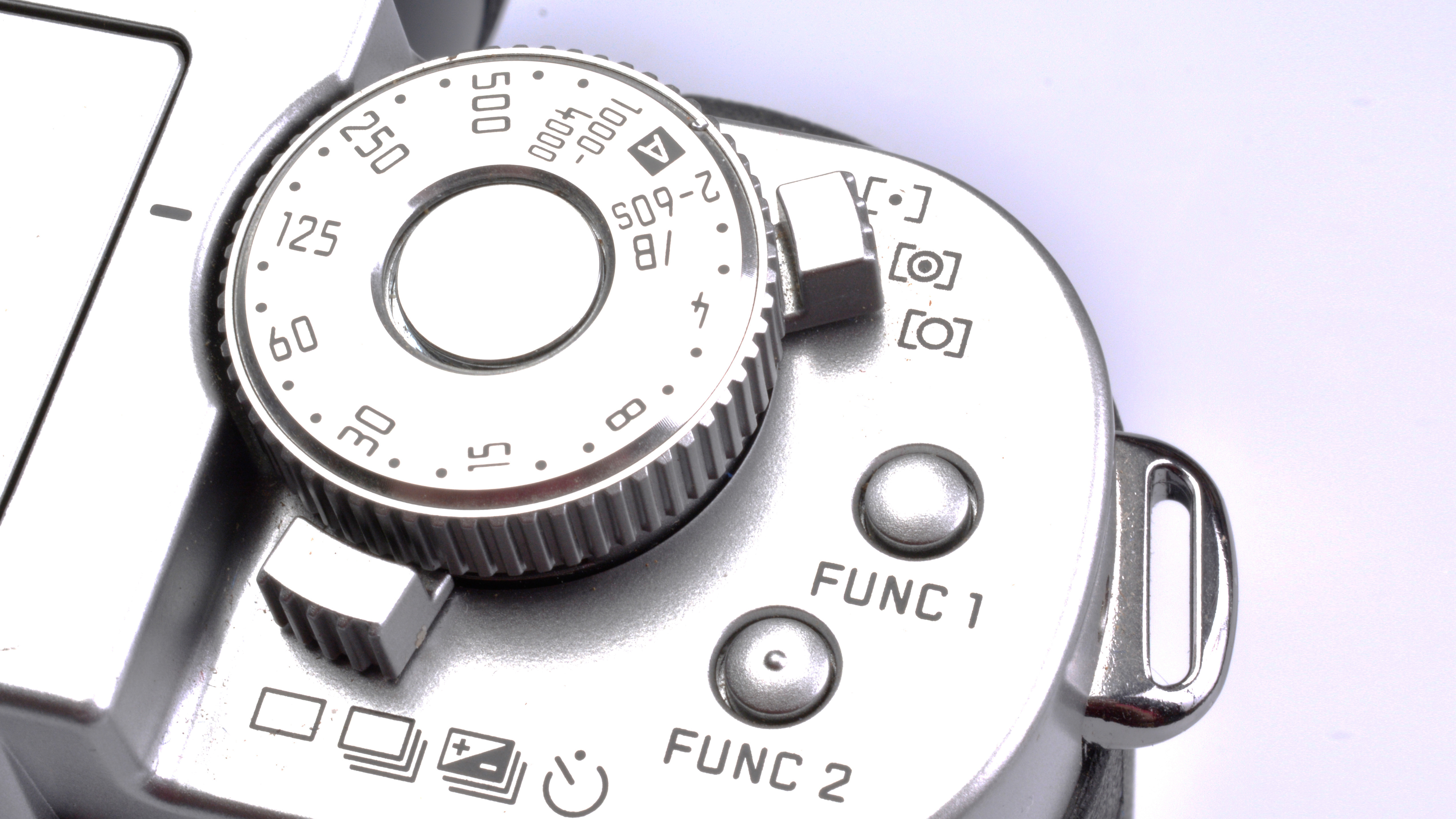

As noted earlier, the Leica’s Live MOS (CMOS) sensor has an effective resolution of 7.5 megapixels and a total count of 7.94 million, while the sensitivity range is equivalent to ISO 100 to 1600… this highest setting being another obvious indicator of the camera’s vintage. So is the maximum continuous shooting speed of just 3fps, but the burst lengths with JPEG shooting can be very long (depending on the memory card in use).

JPEGs can be captured in superfine, fine or standard quality settings with a maximum image size of 3136x2352 pixels. RAW+JPEG capture is available but, curiously, a RAW file can’t be recorded separately. There’s a single memory card slot for the SD format and it supports the higher-capacity SDHC types (which are also faster), but predates SDXC and UHS-II.

In addition to the styling, Leica’s input into the Digilux 3 was a tuning of the image processing which, at the time, it stated gave “picture characteristics that are well known to Leica System camera users”. There’s a choice of seven Film Modes – four for colour and three for B&W. The colour modes are tagged Standard, Dynamic, Nature and Smooth. The three beyond Standard deliver, respectively, increased saturation and contrast, brighter primary colours, and lower contrast. The B&W modes are labelled Standard, Dynamic and Smooth, and essentially vary the contrast. In addition, there are two user-defined My Film presets which have adjustments for contrast, sharpness, colur saturation and noise reduction. This is pretty much your lot for processing JPEGs in-camera, but then even the likes of the contemporary Q series Leicas still don’t offer a whole lot more.

Exposure control is based on one of three metering methods – multi-zone, centre-weighted average or spot. With the optical viewfinder, multi-zone metering is via a separate 49-segment sensor, but in live view, it’she playback modes include a slide show with adjustable display times, nine or 25 thumbnail pages, calendar thumbnails and a zoom function with magnification of up to 16x. Images can be tagged as favourites and the slide show function can be set to only replay these pictures.

The Leica D Vario-Elmarit 14-50mm f/2.8-3.5 ASPH zoom is equivalent to 28-100mm and has built-in optical image stabilization. It’s quite a big lens, but very sharp and well-corrected across its focal range.

As also previously mentioned, it has a Four Thirds mount which is different from the Micro Four Thirds lens fitting of the mirrorless era. There was only a total of four Leica-designed and Panasonic-built lenses (three zooms and a ‘fast fifty’), but Olympus eventually built up a system of 20 models, plus there were 14 in all from Sigma, although a number of these – such as the monster 300-800mm telezoom which is equivalent to 600-1600mm – were quite short-lived.

Olympus maintained production of its Four Thirds system lenses until early 2017, so many of them remain relatively easy to find secondhand and, as with the current Micro Four Thirds OM System lenses, the high-end optics – dubbed Super High Grade and the equivalent of today’s PRO level – are excellent.

The Digilux 3 is comfortable to handle and straightforward to use even if the plethora of buttons does look a bit daunting at first. In practice, everything is pretty obvious and you don’t ever have to go searching for something hidden away in a menu somewhere. Of course, there’s none of the numerous frills and frippery that load down today’s cameras – with, as it happens, the exception of most digital Leicas – but the Digilux 3 lacks nothing of any great importance, so the user experience is refreshingly pure. Aside from the small monitor screen’s low resolution and dynamic range, there’s not much else that betrays this camera’s vintage, but obviously the key question is whether the image quality stands up to today’s expectations. In fact, it’s surprisingly good from ISO 100 to 400, and still quite acceptable at ISO 800. The absence of any sensitivity settings beyond ISO 1600 isn’t especially restrictive unless you do a lot of low-light shooting.

The out-of-camera superfine JPEGs are nice and punchy with, again surprisingly, a fairly wide dynamic range mostly thanks to the 5.51 microns pixel size. However, the 7.5MP resolution is still enough to deliver plenty of well-defined detailing and nicely smooth tonal gradations

Verdict

With its classic rangefinder-type camera styling, the Digilux 3 looks like it could be a contemporary Leica – and, indeed, was mistaken for one by an interested bystander when we were out shooting – and it certainly handles much like a digital M… albeit with quite a few more external controls. Although it’s essentially the Panasonic L1 under its bespoke magnesium alloy bodyshell – which is no bad thing – the Digilux 3 feels a little more special and it’s certainly more intuitive in its operation than quite a number of contemporary mirrorless designs. In many ways, it’s actually quite film-like in its feature set and functions, but with all the key benefits of digital capture.

The main technical limitations are the three-point autofocusing, the limited high ISO options and the 3fps maximum continuous shooting speed, but none may be a big issue for some shooters. Of course, you go without any video capabilities, but again this probably won’t concern anybody who is primarily looking for a different photo camera experience. There’s no question the Digilux 3 is good fun to use, but it is also definitely more than just a plaything and could very easily serve as your ‘everyday’ digital camera.

Values are holding up well because it’s an inherently strong camera with no major reliability issues, but obvious too because – despite the mixed parentage – it wears the famous red dot badge.

Check current offers on the Digilux 3 on eBay.com or on eBay.co.uk

Check out the best Leica cameras you can buy new today