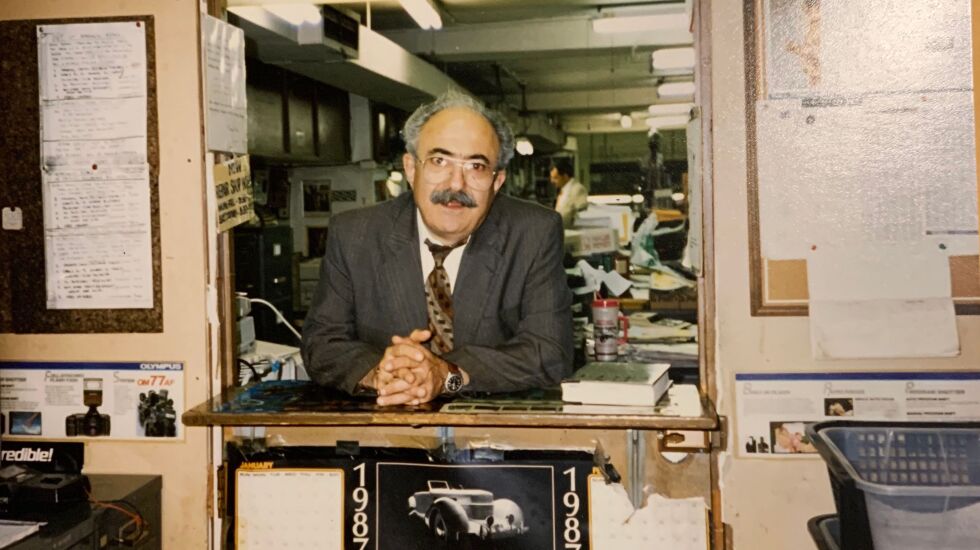

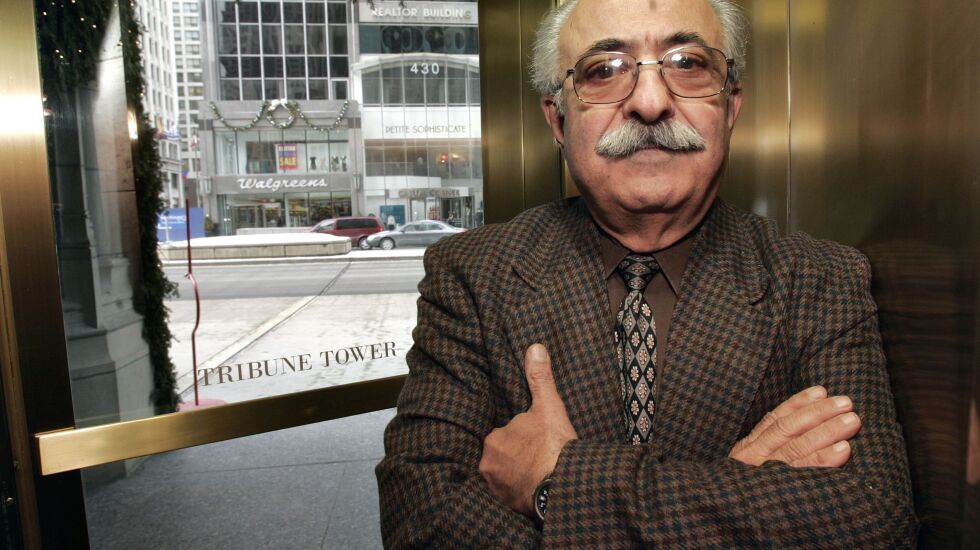

Paul Zimbrakos schooled generations of Chicago reporters with the arched eyebrows of a knowing, skeptical editor, but made fledgling journalists swell with pride when he bestowed them with his highest praise — “Attaboy” or “Attagirl.”

Mr. Zimbrakos, 86, died Tuesday at Loyola University Medical Center, according to his son, Vasily, and daughter Marianthe Zervas. He had been ill with liver disease and then “COVID stepped into the picture,” his daughter said.

He worked from 1958 to 2000 at the City News Bureau of Chicago, which over a 115-year-history produced esteemed reporters and writers including “Front Page” co-author Charles MacArthur, Mike Royko, Seymour Hersh and Kurt Vonnegut.

After a reorganization and new name–City News Service–Mr. Zimbrakos continued working there until its closure in 2005.

Seven days a week, 24 hours a day, “Zimbo’s” reporters used to fan out all over the city to police stations, O’Hare Airport, City Hall, the Cook County Building and state offices, where they’d pick up tips and break news stories that were chased by the city’s radio and TV stations and newspapers.

Its young journalists learned to ask if bodies were found face up or face down, what was on the menu for Thanksgiving dinner at Cook County Jail and the precise definition of a 5-alarm fire. They covered everything from dog shows to plane crashes to the crawlspace crowded with bodies at John Wayne Gacy’s house.

Mr. Zimbrakos coaxed them on questions they needed to ask and to go back — over and over — to a source if they overlooked a detail.

With his luxurious mustache and twinkling eyes, he had a quietly merry presence. “He was a very warm-hearted guy,” said CNB alum John Holden.

But he was no-nonsense too.

When his staffers wrote up holiday stories around December 25 and titled them “XMAS,” he’d cross out the X, saying: “Ah, let’s keep the Christ in Christmas.”

If a reporter forgot something, “He had very expressive eyes and eyebrows, and he could devastate you without saying a word just by arching an eyebrow and looking at you,” Holden said. “You certainly didn’t want to let Paul down.”

Many journalists across the country still “do” imitations of Mr. Zimbrakos saying, “Ah, ah, what about this detail?” And they never forgot the old CNB phone number: 782-8100.

Young reporters needed “honesty,” Mr. Zimbrakos once said, “the ability to talk to people and not to worry about your ego, especially since it’s going to take a battering when you’re learning.”

Mr. Zimbrakos “believed in being a good person,” his son said. “He never cussed, and he didn’t like it if we cussed. He wanted us to be good, but he wasn’t a totalitarian type.”

“He wanted you to be the best you can be,” his daughter said.

Mr. Zimbrakos welcomed everyone to his home for celebrations like Greek Orthodox Easter. He could talk about literature, Greek history, current events and City News Bureau tales.

“Everyone wanted to be around where he was,” his son said.

His parents were both from the Greek island of Crete. His father William worked as a milk dealer.

Young Paul went to Austin High School. “I always enjoyed writing, even term papers,” he said in a Sun-Times interview.

In the late 1950s, Mr. Zimbrakos served in the Army. He was in boot camp at Fort Hood, Texas, at the same time as Elvis Presley.

“He always would comment that Elvis had bought a jukebox for [Elvis’] barracks,” his son said.

He worked as a copyboy at the Chicago Daily News before joining the City News Bureau at 188 W. Randolph.

At the time, “We still had the pneumatic tubes that went down to the basement (and through the city’s underground tunnels around the Loop) for all the papers. Dispatches were tucked into metal canisters and whisked across town by air pressure,” he told the Sun-Times.

Mr. Zimbrakos earned a political science degree from Roosevelt University.

His River Forest home had a bounteous herb and vegetable garden once tended by his wife, the former Eleni Orfanoudakis. She died in 2005 while visiting Crete, where she’d been born in the village of Kalyves.

They married in the mid-1960s, four months after they met. She was en route to Chicago to join a sister who’d already immigrated. When their aunt sent her husband to pick up Miss Orfanoudakis in Windsor, Canada, he brought along his grand-nephew: Pavlos “Paul” Zimbrakos.

During his career Mr. Zimbrakos won many honors, including an induction into the Chicago Journalists Hall of Fame. He also taught journalism at Loyola University.

In addition to his daughter, Marianthe, and son Vasily, Mr. Zimbrakos is survived by his son, Kostas, brother George and four grandsons. Arrangements were pending.