The ending of the novel Yesuvin Tholargal (Comrades of Jesus) by noted Tamil writer Indira Parthasarathy would have been heartening to comrades of the time — “We are all waiting for the arrival of Jesus. But instead of a cross, he will hold a hammer and sickle,” says Asha, a character in the novel set in Poland.

Asked why the euphoria of the first half of the previous century only climaxed in despondency, Mr. Parthasarathy, sought to justify his red-tinted glasses, saying Poland, steeped in a happy blend of Christianity and Marxism could have ushered in a new era. “You must keep in mind that the Communist Party there not only built offices for itself, but also constructed the famous St. Paul Cathedral. Still, the system failed because of excessive police control and the failure of the Communist parties to adapt Marxism to the cultural needs of the varied countries where they had come to power,” said Mr. Parthasarathy, who had served as professor of Tamil at the Warsaw varsity for five years.

Not to forget he had been a member of the Communist Party of India (CPI) during his student days in Kumbakonam and later in Annamalai University in Chidambaram.

He said that even Karl Marx’s calendar for revolution failed. “He visualised it to happen in England, the most advanced industrialist country since he was sitting and reading in the British Library. It took place in an agrarian society in Russia,” said 92-year-old Parthasarathy, one of the few writers who closely follow the political developments in the country.

“Unless the Opposition parties in India sink their ego and come together with the single agenda of taking on the BJP, the party will come to power once again in 2024. The Congress party has become a laughing stock. If the BJP is re-elected with as much majority as it has now, the party will make India a Hindu rashtra and will make amendments to the Constitution to fulfil its agenda,” warned Prof. Parthasarathy, who had worked in Delhi University before his tenure in Warsaw. Later he joined the Department of Drama in Pondicherry University.

Indira is the name of his wife, who encouraged him to send his story Manitha Enthiram (Human Machine) to Tamil magazine Ananda Vikatan, which was published as a star story in 1962. His short stories have been published in two volumes. His play Ramanujar won the Saraswathi Samman award.

Fertile ground

Born in Chennai and brought up in Kumbakonam, Mr. Parthasarathy had the advantage of living, observing and participating in an environment of intense political and literary activities. Kumbakonam was the birthplace of some of the finest writers including Ku.Pa. Rajagopalan, Na. Pitchamurthy, Karichankunju and M.V. Venkatram. Another writer T. Janakirman lived there and taught Mr. Parthasarathy at school. Mr. Parthasarathy lived in Saranagapani Sannidhi Street where mathematical genius Ramanujan also lived.

The composite Thanjavur, in which Kumbakonam was a part, was a nerve centre of the Communist and Dravidian Movement, and Mr. Parthasarathy, known as ‘Epaa’ in the literary circle, was inevitably drawn by the political and literary currents of his time.

A massacre retold

He shocked his father, who was dreaming of his becoming an IAS officer, by joining for a masters in Tamil in Annamalai University. “It was an aspiration of every Brahmin father then. He thought I was studying English literature. But it was my desire to study Tholkappiyam with commentaries by Senavarayar. I have no regrets,” laughed Mr. Parthasarathy, who later wrote Kuruthipunal, a novel, based on the massacre at Keezhvenmani, in the then composite Thanjavur district, where 44 Dalits were burnt alive in 1968. It won him the Sahitya Akademi award in 1977 and was also made into a film.

“When the novel was published, the CPI(M) took objection saying that I have diverted the issue by portraying the landlord as impotent. I looked at the Keezhvenmani massacre from the Freudian angle because among those who were killed were 26 women and 12 children. Why women and children?,” he asked.

The title Kuruthipunal, he explained, was from a poem in Kambaramayanam in praise of Parasurama, and recalled the entire lines from his memory.

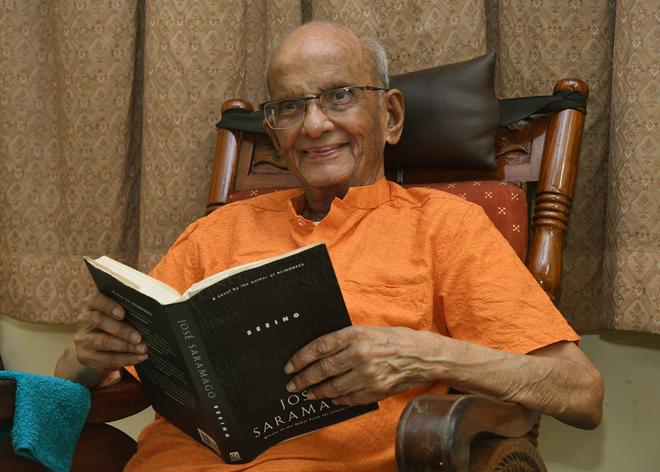

He also explained that he had suggested the title ‘Poisoned Root’ for the English translation of his novel Ver Patru, though it is slightly inaccurate and could even convey a negative meaning. “I got the idea from Eedu, the commentaries on Vaishnavite literature. If the root is poisoned, it will poison the tree. The root in my novel is the caste system, which is poisonous,” said Mr. Parthasarathy, who has an in-depth knowledge of classical Tamil literature and on his table nestling among Tirukkural and Kamba Ramayanam, is the novel of Portuguese Nobel laureate Jose Saramago.

But his literary works do not show off his scholarship. “Scholarship should be integrated with storytelling and should not prove difficult for the reader,” he said.

He also does not agree with the claim of some writers that they write primarily for themselves.

“A kite would emerge in the sky only when there is wind to sustain it. When an incident affects me, I react by writing. The plot develops when two characters start the conversation. I do not know how my story ends,” he said.