Runners had a seedy reputation in the mid-1970s. At least among old guard gatekeepers like Chicago Park District Supt. Ed Kelly, who wasn’t about to permit thousands of joggers to stampede through his parks.

“He apparently clung to the earlier view of runners as undesirables, a near-criminal element,” Andrew Suozzo writes in his history “The Chicago Marathon.”

So those passionate about creating a marathon in Chicago turned to Lee Flaherty, whose Flair Communications did marketing work for the city.

“Flaherty was politically connected and was able to get Mayor Daley interested in the marathon,” Suozzo writes.

Then, Daley died, and Daley’s successor Michael Bilandic, himself a runner, was even more interested. He green-lighted the marathon, first held in 1977.

Flaherty, who championed the Chicago Marathon in its early years, even paying for it himself for the first two years, until it found a corporate sponsor, died March 23 at his home in Flair Tower, the building he helped develop on Erie Street. He was 90.

He was a pioneer in redeveloping River North, opening Flair Communications on Erie Street in 1964 when the area was downtrodden.

He also helped create, in 1984, the World’s Largest Block Party, an outdoor festival that encouraged young people to linger downtown after work in an era when you could shoot a cannon down State Street at 6 p.m. and not hit anybody. The street party also provided a lifeline to Old St. Patrick’s Catholic Church at a time parish membership had dwindled.

“When I came in 1983, Lee was a fixture at St. Pat’s,” the Rev. Jack Wall said. “When I became pastor and we started the block party, Lee really put his arms around it and helped us.”

Flaherty claimed the block party was his idea, just as he insisted he was the founder of the Chicago Marathon, though hosting the 26.2-mile race wasn’t a particularly innovative idea: Detroit, Duluth, Minn., and San Francisco all started marathons the same year as Chicago.

Then again, Flaherty was a professional promoter, and that included polishing his own myth.

The Chicago Marathon, River North and the World’s Largest Block Party all were valuable contributions to the city. But, as someone who knew Lee Flaherty for almost 25 years, those achievements always seemed sidelights to the general splendor of the man: an exuberant bon vivant, old school “Mad Men”-style sharpie who rode around town in a chauffeur-driven Rolls Royce, had epic martini lunches and was always deeply tanned and immaculately dressed with his French cuffs and tailored Pucci suits.

I met Lee in 1997.

“I think you’re a genius!” he said then. “You’re going to work for me!”

And I did, freelance, briefly, writing for the first website for Brown & Williamson Tobacco. So, to some, I could be seen as too compromised to assess the man’s life. But I knew him, which also puts me in a position to tell his story without pulling punches.

Though chronicling his life raises the classic publicity conundrum: Are you getting to read this because it’s intrinsically worth writing? Or because somebody is doing a favor for a friend? You’ll have to decide that for yourself.

Lee Flaherty was a good friend to have.

“If he was a friend of yours, he was the best friend you ever had,” said Peter Rogers, former CEO of Brach’s and of Nabisco Brands. “Flamboyant, extravagant, he was just so full of life. But don’t get on his wrong side. If he didn’t like you, watch out.”

Le Grand Francis Flaherty was born in Indianola, Nebraska — a drugstore owner he worked for at 13 found that name awkward and dubbed him “Lee.”

His father John deserted the family. His mother Frances, a seamstress, moved Lee and his older brothers Dennis and Russell to Richmond, California, across the bay from San Francisco, where he grew up.

Flaherty enlisted in the Army in 1951, a paratrooper with the 11th Airborne. He spent three years in the service, then attended the University of California at Berkeley on the GI Bill, graduating in 1957.

After college, Flaherty came to Chicago to work for the marketing group of the Schmidt Lithograph Company. At the time, printers created marketing materials directly for product manufacturers — point-of-purchase displays, flyers and such.

After five years, Flaherty decided to go into business for himself, producing the creative end of that business — basically serving as an ad agency for direct mail, contests and in-store branding.

His mother offered to mortgage her home to help him. He told her not to. But she did that anyway, mailing him a check for $8,500 and earning a lifetime of gratitude that impressed his friends.

“He was a man who loved his mother more than any man I’ve ever known,” Rogers said.

Flaherty rented a dilapidated brownstone at 214 W. Erie St. for $85 a month, and, on Nov. 1, 1964 — Flaherty had a head for dates — he opened Flair Merchandising, “Flair” having been his nickname in the Army.

Flair started with three clients: Morton Salt, Accent International and Alberto-Culver. In 1966, the company grossed more than $1 million. The next year, revenues doubled.

He also did marketing for Rolls Royce and was given a car in lieu of payment. Eventually, he was given three, with the most recent usually parked in front of Flair House.

At one point, Flair had over 100 employees, with offices in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Detroit and New York.

Flaherty was followed to Chicago by Sharron Lee Gleason, a pinup model named “Miss San Francisco,” whom he met when she graced a boat pulled by Jack LaLanne, a lifelong friend, as he swam under the Golden Gate Bridge, a birthday tradition for the famed fitness guru. Gleason was 17. Flaherty was 25. She followed him to Chicago. They got married in 1960 and had a daughter, Shannon. The couple divorced in 1966 but kept close.

“Mom lived a block away from him,” said Shannon Flaherty Micheletto, 59. “She just loved him. She called herself Mrs. Flaherty as if they never got divorced.”

Flaherty was athletic his entire life.

“He’s always been Mr. Fit. He weighed 168 pounds,” his daughter said. “I’ve got pictures of him just finished from the Army, all oiled up, and a picture of him 40 or 50 years later. His body is exactly the same. It’s crazy.”

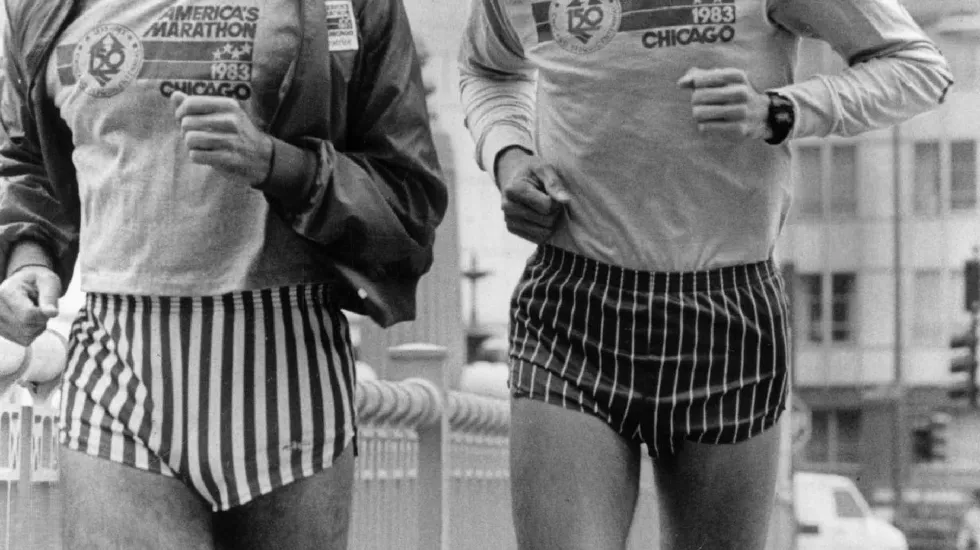

In the mid-1970s, he embraced running.

“The ultimate of the work ethic is running; that’s why I love it,” Flaherty told the Sun-Times in 1977.

He first ran the Boston Marathon in honor of the American bicentennial in 1976. The Chicago version that he helped create was first called “The Mayor Daley Marathon.” Meant as a one-time tribute to the late mayor, it was held on Sept. 25, 1977.

But then came a second year, and complaints flooded in about what one critic called “The Lee Flaherty Marathon” — from the doubled entry fee, later starting time (more spectators that way, Flaherty reasoned) and general commercialization and dubious quality of the merchandise.

“It’s becoming like the Indy 500,” parks advocate Erma Tranter complained.

In 1979, Flaherty invited Beatrice Foods to become the exclusive sponsor, and the race became America’s Marathon Chicago.

As the marathon grew, its sponsorship passing from Beatrice to LaSalle Bank to Bank of America, Flaherty increasingly grew bitter about the race, feeling he wasn’t getting the credit he deserved.

“He wanted his marathon back,” his daughter said. “We all wanted him to stop, and he couldn’t. He was just so obsessed about getting it back. He burned a lot of bridges.”

“He could not get over they didn’t attribute the marathon to him,” Rogers said. “He thought it was one of his big contributions to the city of Chicago. Toward the end, he got very bitter about it.”

“Some of the demons of his life took over,” Wall said. “It was very sad to see.”

Over the past decade, Flaherty mellowed, having closed his business and helping develop Flair Tower at 222 W. Erie St., which features 150 artworks from his collection in its hallways on each of its 26 floors.

Among the honors that Flaherty and Flair Communications won, he was most proud of being named a Knight of Malta in 1984 and receiving the Horatio Alger Award in 1979.

In 2010, the Illinois Landmarks Commission honored Flaherty as a “Chicago Legend,” along with Ernie Banks and Harold Ramis.

“He adopted Chicago,” Rogers said. “He was a great promoter of Chicago. He really loved Chicago and did everything he could for the city.”

“He was very unique, a one-of-a-kind kind of guy,” Wall said. “He really was. He came from pretty humble origins and certainly made his mark. His dream for the Chicago marathon was really ahead of his time.”

“He loved to party, he loved to take people out,” said Micheletto, who survives him along with her daughters Carley and Mia. “He said to me, ‘I don’t have any regrets. I’ve had such a good life, I’ve been so blessed. I don’t want anyone to be sad that I’m gone. I really had it all.’”