One of Hong Kong’s most reputable sources of public opinion data will stop releasing its poll results on a series of sensitive questions to the public, including on China’s Tiananmen Square crackdown in 1989 and Taiwan independence, in another example of the city's shrinking freedoms.

The Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute said last month it was planning to limit its survey scope, sparking concerns over the availability of information about the opinions of Hong Kong residents.

On Thursday, the institute announced that the survey results of some 50 questions, or about a quarter of its existing questions, will be limited to internal use, academic research and commissioned services starting this month.

They included ones asking respondents whether they thought Beijing students and the central government “did the right thing” during the 1989 crackdown, in which hundreds and possibly thousands of people including many students were killed, and if they support Taiwan becoming independent.

About a quarter of its existing questions will be completely removed after its operation review, he added.

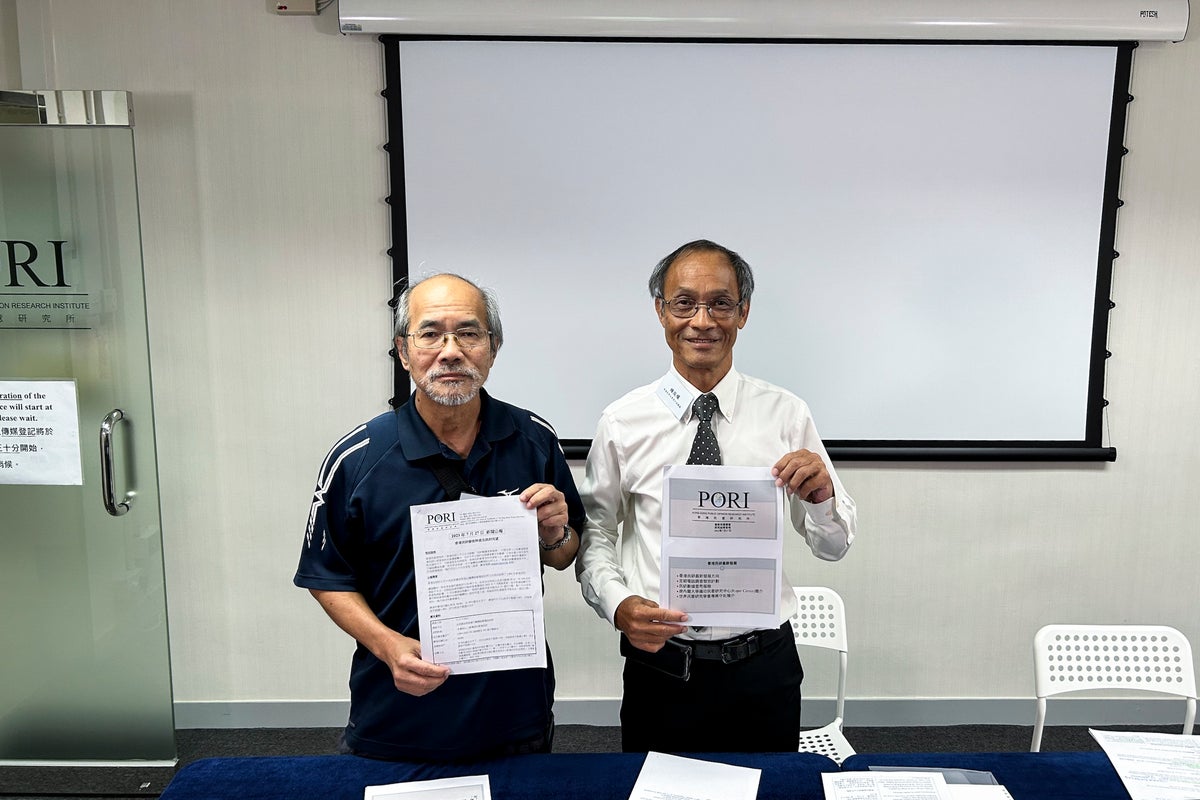

“We need to ‘dance’ with the times," its president, Robert Chung, said at a news conference.

Supporters said the survey restrictions will cause a great loss for Hong Kong. Freedom of expression was once a hallmark of the Chinese-ruled former British colony.

When the city returned to Chinese control in 1997, it was promised it could retain its Western-style civil liberties for 50 years after the handover. But critics say its freedoms eroded with the enactment of a Beijing-imposed National Security Law and other political restrictions following massive 2019 pro-democracy protests. Large numbers of democracy supporters and a portion of the educated middle class have left the city.

Chung said his team considered factors such as public demand for its data, how widely their results have been used and previous government risk assessments on their work before making the revisions. Their conclusion was that the institute needs to conserve its resources, he said.

“In a way some of those questions might have generated some unwarranted political disputes, which we did not intend to do,” he said.

The veteran pollster said “the risk factor is important" during its deliberation. But he denied his team was practicing self-censorship, insisting that they were not ceasing certain survey work due to fear.

The institute, nevertheless, canceled its planned release of a survey conducted on the anniversary of the crackdown on the 1989 pro-democracy protests at the advice of a government agency in June. The institute did not identify the government agency at that time.

For decades, the institute’s survey questions have been a valuable gauge of public sentiment in the city on various issues, including people’s sense of identity. One of its polls asked residents if they identify themselves as Hong Kongers, Chinese, Chinese in Hong Kong or Hong Kongera in China since 1997.

After the passage of the tough security law, the institute continued to conduct politically sensitive surveys, including asking about residents’ satisfaction with police performance. But the questions that tracked people's sense of identity and the police's rating will be moved into the private category.

Chung said future survey results planned for internal use under the changes will be available on a data inquiry platform in which users will have to declare that the data will not be used illegally.

Before Chung launched the independent institute, he was the director of the public opinion program at the University of Hong Kong, the city’s oldest university. Over the years, his work has drawn criticism from pro-Beijing media and organizations.

In January 2021, when more than 50 pro-democracy activists were arrested on subversion charges over an unofficial primary election in the city’s biggest national security crackdown, police also raided his institute, which was involved in organizing the voting.