When he was a high school student in the 1980s at Marmion Military Academy in Aurora, a former suburban man says he was assigned to collect athletic equipment after intramural sporting events at the Catholic boarding school and take it to a secluded “basement area.”

The former student says that’s where a monk named Jerome Skaja — a member of the Benedictine religious order that still runs the nearly century-old school — sexually assaulted him more than a “half dozen times” his sophomore year.

“I was prepubescent at the time of this; I was a little kid,” the former student, a lawyer who worked for years as a prosecutor, tells the Chicago Sun-Times.

Asking to be identified only by his initials, J.K., the attorney says he was something of a troubled kid and didn’t have a great family life: For Skaja, a physically imposing man who died in 2016, “I was easy pickings.”

He says he eventually went to the Rev. Vincent Bataille, then the dean of students, to report what happened.

“He told me to treat it as a dead subject — not to tell my classmates, not to tell my parents,” the attorney says.

No records could be found to indicate Bataille ever notified the police, though Illinois law then, as now, requires school officials to report suspected child abuse.

J.K. says he wasn’t offered counseling or an apology and that no one from the school ever contacted his family.

Skaja — who oversaw intramurals and was involved in fundraising for the school, which has since dropped its boarding and mandatory military programs — remained at Marmion.

That was even though the mother of one of the teenager’s classmates confronted the Rev. David Cyr, who was the abbot in charge, after hearing from her son about the accusations.

“He treated my mother as a hysterical woman,” the former classmate says.

Another former classmate also says J.K. told him at the time he’d been sexually assaulted.

A school yearbook from what would have been the attorney’s senior year shows Skaja was at Marmion then. But J.K. was gone, kicked out between his junior and senior years, accused of vandalizing his dorm room.

It isn’t clear when Skaja left the order or why. His death notice called him a “former teaching Brother in the Order of Saint Benedict at Marmion Abbey.”

J.K. says of the monk: “He was a very well-liked guy, very social. It occurs to me now that he probably brought a lot of money into the school” through his fund-raising role.

The man says: “It was a 14, 15-year-old kid against this institution, sequestered away.”

A policy of secrecy

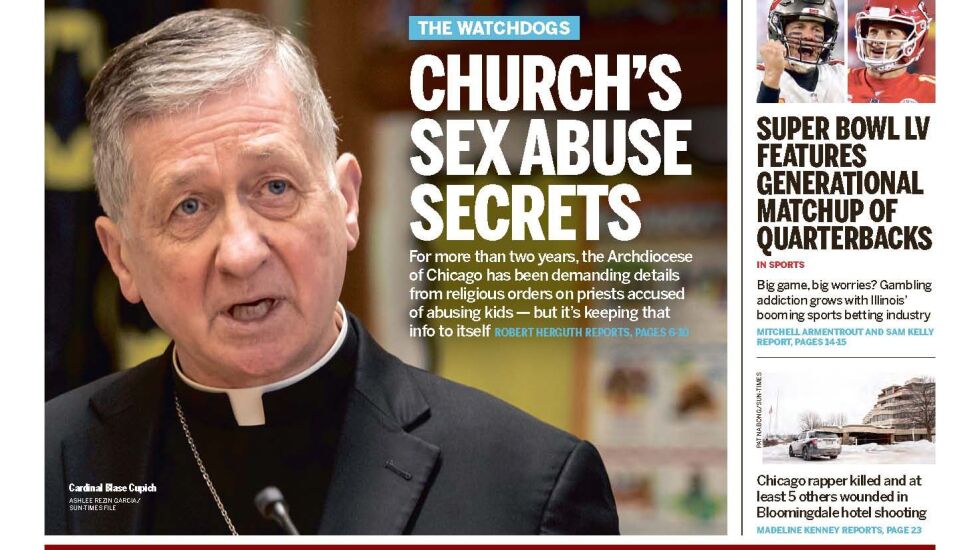

In a series of stories since last year, the Sun-Times has reported that numerous Catholic religious orders operating in the city and suburbs continue to keep secrets regarding sexual abuse of minors by their clergy.

No Benedictine abbey in the Chicago region posts a public list of clergy members who have been deemed to have been credibly accused of sexual abuse. Some other orders that operate in the Chicago area similarly provide no such public accounting, the Sun-Times has reported.

But others, including some of the better-known orders such as the Jesuits, have done so. And so have many Catholic dioceses — some following lawsuits, some to promote healing and greater transparency in the wake of abuse scandals that have emerged in waves since the 1980s.

According to BishopAccountability.org, a nonprofit church watchdog, more than 130 Benedictine brothers and priests have been accused of sexual misconduct around the country, with the accusations largely involving children. Based on court records and news accounts, five served in or near Chicago.

Among them, Brother Joseph Charron, a member of the Benedictine order who taught at Marmion and was charged earlier this year with sexually abusing a student for years, as recently as 2015.

Patrick Wall, a former Benedictine monk, now works for a law firm that has filed numerous lawsuits against church authorities over sex abuse. He says the number of Benedictine clergy to have sexually abused minors is likely to be higher than what’s become publicly known. He cites the order’s practice of quickly and quietly settling claims before they go to court.

“I’ve been aware of Benedictine child abuse cases since 1991 in the United States, and I do not know of a monastery that has willfully come clean,” Wall says. “They’ve only come clean at the end of a barrel of a legal gun.”

Sources who spoke with the Sun-Times identified other Chicago-area Benedictines they say molested them when they were minors, were otherwise sexually inappropriate with them or covered up sex abuse.

Skaja is among them. The accusations against him are now being investigated by his order, according to a spokeswoman for the Diocese of Rockford, the arm of the church covering Aurora. She won’t say whether that investigation began before the Sun-Times asked about J.K.’s accusations or why it’s happening now, given that Marmion leaders were told of the allegations 30 years ago.

The Sun-Times learned that J.K. reached an out-of-court settlement with the order after he was out of high school and that it included a confidentiality clause — a strategy sources say the Benedictines have used in other cases involving accusations of sexual misconduct.

Bataille, the former Marmion dean, remains affiliated with the Marmion Abbey, though in an elevated role. He is the abbot overseeing a consortium of Benedictine monasteries with nearly 500 monks across North America and beyond. He didn’t respond to calls and emails seeking comment.

Founded in the 6th century, the Benedictines’ St. Peter Damian once railed against child sexual abuse, complaining to Pope Leo IX around 1049 that children were being forced into sex acts by priests and bishops.

Benedictine abbeys who keep secrets on child sexual abuse today “have to own the fact that some of their own raped and tortured and committed crimes against children,” says the Rev. Gerard McGlone, a Jesuit priest who studies clergy sex abuse and who was sexually abused by a priest as a minor.

“The essence of being penitent” is “you admit your sin and be accountable for it and seek penance,” he says.

The Rev. John Brahill, the abbot of the Marmion Abbey that still runs the Aurora school, “made the decision not to participate in an interview” but says in a written statement:

“Our most important priority at Marmion is the safety and well-being of our students. We follow the strictest protocols to protect those entrusted to us. This includes immediately reporting any allegations of abuse to relevant child protection or law enforcement authorities, as well as immediately removing any accused person from the school pending an investigation.”

‘He got touchy-feely’

Christopher Kohler, a Michigan attorney, says that while a freshman at Marmion in the 1980s, he was sitting on the floor in the library building doing school work when a priest who worked in the administrative offices asked what he was doing. Kohler says he told him he was working on a paper and that the priest said he could use the computer and printer in his office.

Kohler says that, “on more than one occasion” while he was a student there, the cleric sat next to him and placed his hand on the boy’s inner thigh, making him uncomfortable.

“He got touchy-feely with me,” he says.

Kohler says another priest who lived in the student dormitory later told him that the priest who’d allowed him to use his computer had staked a claim on the teenager as his sexual “property” and was engaged in a tug-of-war with another Marmion priest over him.

Kohler says he was stunned and that he owes a lot to the dorm priest who “warned” him away from the two clerics — both now dead.

He says the dorm priest told him, “Keep your distance” from them, though “he was super-conflicted when he told me,” saying, “God, I hope I’m doing the right thing.”

‘Don’t worry about sinning’

Another man who attended Marmion years ago — as a day student, not a boarder — was an altar boy at his home parish, St. Therese Church in Aurora, when he was molested by a priest, according to court records and interviews that provide this narrative of what happened:

In 1990, the Rev. Augustine Jones, a Benedictine who was a visiting priest from Marmion, was the officiant. When Jones discovered his altar server was a Marmion student, he asked him to stay after mass to talk. While taking off his vestments in the sacristy, the priest grabbed the boy’s hand and placed it onto the cleric’s erect penis and grabbed the boy’s private area.

Then, while driving the boy home, Jones told him: “Don’t worry about sinning. The juices gotta flow.”

Before the boy got out of the car, the priest gave him a $20 bill.

The student later went to confession and told the priest there, the Rev. Michael Burrows, what happened. Burrows, a priest still at Marmion, asked the teenager to return later to talk more.

When he did, Burrows asked the teen to tell him again what happened — with the boy not realizing right away that another Benedictine, the school’s headmaster, was in an adjacent room, listening.

Soon after, Cyr, the abbot, called the boy to his office and asked: “Are you sure this is true? Are you positive?”

The boy told him, “Yeah, it happened.”

Cyr, who died in 2018, said of the accused priest: “If he needs therapy, we’ll get him help . . . You keep your head in your studies, and don’t talk of this because we don’t want scandal,” according to a source.

The Benedictines didn’t call the police or offer the victim counseling, the source says, but assured the boy, “You’ll never have to worry about him again,” and moved Jones away.

‘A late-night swim’

A year or two later, the boy spotted Jones in a building on campus.

As a military school, Marmion students routinely dressed in military garb and sometimes carried sabers. The teenager considered driving his blade through Jones, the source says. But another monk saw the boy was upset, asked why and ushered him into the headmaster’s office.

The boy told him he’d been promised he’d never see Jones again, and the headmaster offered to cover the student’s tuition and other expenses from then on, the source says.

After graduation, the victim went to the police to file a complaint against Jones, who was charged in 1993 with aggravated criminal sexual abuse.

Burrows was among witnesses subpoenaed in the case, court records show.

Jones, who died in 2007, pleaded guilty and was sentenced to six months in jail and ordered to register as a sex offender.

The victim sued the Benedictines, settling for under $100,000 and agreeing to keep the settlement confidential, according to interviews and records.

Jones’ lawyers asked the judge in the criminal case to block prosecutors from bringing up that, years earlier, the priest had been convicted of taking “indecent liberties” with another Marmion student. That charge was the result of Jones groping a boy during a late-night swim in 1968, records show.

In that 1968 case, several Benedictines wrote to push for probation for Jones.

The Rev. Mario Pedi, who died in 2015, said in one of those letters that Jones was “very kind and considerate of others, giving of himself both in the teaching field and in the ministry.”

“He does have a problem with homosexuality, and this has been a cause of worry both for himself and for our community,” Pedi wrote. “Because of this problem, he had been removed from teaching, hoping that this would prevent contact.

“For several years there has been no problem,” Pedi wrote. “In all the years I have known him, I believe that he never forced himself upon anyone. He almost seems to be begging for affection, rather than seeking a sex act. If I felt that he were a danger to society, I would recommend some kind of restriction.

“I feel, though, that he can be controlled, and that probation is wise. He can continue to do a great deal of good as a useful citizen, and at the same time not corrupt young boys. . . . He is definitely not a danger to society.”

The probation office recommended against prison in that case, writing, “We have been assured by his superiors that he is kept under constant supervision and that whenever he leaves the abbey on business he is accompanied by another priest.”

How and when he was allowed back into public ministry isn’t clear. Brahill won’t comment.

Protecting a predatory priest

While Jones’ case was pending, he moved to St. Benedict’s Abbey in Kenosha County, Wisconsin, records show.

Among the Benedictine monks who’d lived there for decades was Brother Thomas Chmura, who was arrested by the Antioch police in 2013 for attempting to abduct a girl walking in the far northwest suburb. Driving a car from the abbey, Chmura pulled alongside the high-schooler and offered a ride, according to a police report.

After she said no, the report said, he told her, “Come on, you’re so beautiful, let me drive you home.”

When she refused, Chmura said, “Get in the car,” and the girl “ran from the vehicle,” police records show.

After he was arrested, he admitted he’d tried to entice other girls as well into his car for weeks.

His abbey posted bail so he could stay out of jail pending his trial, with a condition that he stay away from minors while back at the abbey.

But the abbey allowed young people on the grounds, violating the terms of his release, and Chmura was sent to jail.

He later pleaded guilty to a felony abduction charge and was sentenced to probation and required to register as a sex offender. He now lives in Missouri at a church-run facility for troubled clergy and couldn’t be reached.

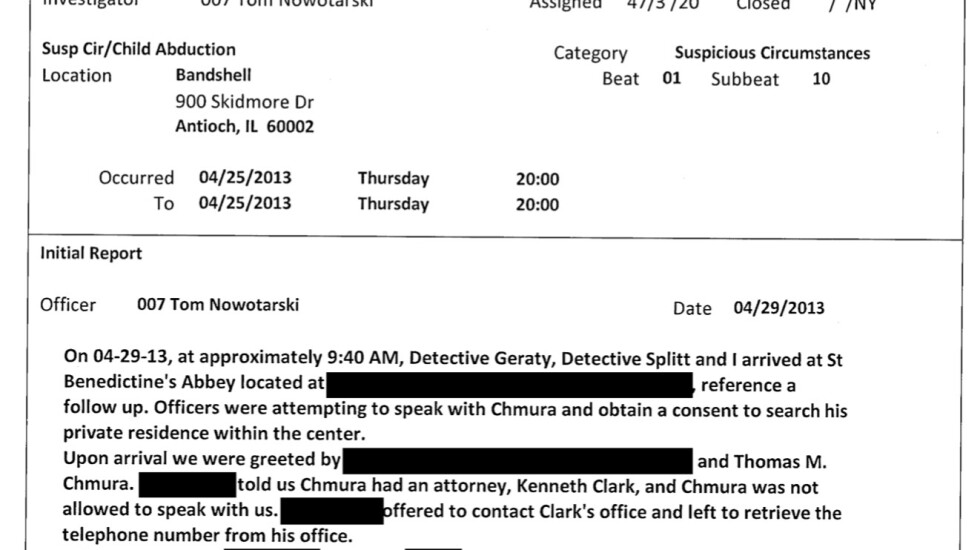

Three days after Chmura confessed, Antioch detectives went to his abbey “to speak with Chmura and obtain a consent to search his private residence within the center,” police records show.

Someone at the monastery — the names on the reports are blacked-out — told police Chmura had an attorney and “was not allowed to speak with us.”

The monk “was upset that Chmura spoke with officers on the night he was arrested” and said Chmura “already said too much.”

The cleric was “upset that information was in the newspapers about the incident” and that police were “on nothing more than a crusade to go after Chmura.”

Benedictine abbeys are self-governing. But St. Benedict’s falls within the geographic boundaries of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee and, as such, operates with the permission of Milwaukee Archbishop Jerome Listecki.

Records show the police contacted Listecki’s office after the unfriendly encounter at the abbey and were told by an aide to the archbishop “that members of St. Benedict’s Abbey should be fully cooperating.”

Soon after, a top official at the abbey spoke with police, telling them Chmura previously was sent to Saint Luke Institute in Maryland “for an issue Chmura had with viewing Internet pornography.”

The official “stated he did not know what type of pornography . . . meaning adult pornography or child pornography,” according to records.

The Sun-Times contacted the Rev. Donald Gibbs — a leader at St. Benedict’s at the time who records show was going to be called as a witness had the case gone to trial — who says he’s been having health problems and wasn’t able to answer questions.

After Chmura’s arrest, police records show, the abbey got a letter from a New York woman whose adult son was receiving letters from Chmura, asking for photos of “your young friends.”

More secrecy

Somebody came forward in 2019 to accuse a Benedictine priest at St. Procopius Abbey, which founded Benet Academy in Lisle, of molesting a Benet student decades earlier.

The Rev. Austin Murphy, the abbot, said recently, “An investigation was completed, and the allegation was found not to be substantiated,” declining to elaborate or identify any police agency that was contacted.

The Lisle police and other agencies say it wasn’t them.

Nor would Murphy provide the names of current or past Benedictines credibly accused of sexual abuse, including at its now-closed St. Joseph Bohemian Orphanage in Lisle that was the subject of a 2011 federal lawsuit by a man who says he was molested by a priest there as a boy.

And Murphy won’t say whether the order found accusations contained in lawsuits against the Rev. Terence Fitzmaurice credible. Fitzmaurice, a Benedictine who served at St. Procopius Church in Pilsen for many years, died in 2009. He’d been accused of impregnating a girl, beating children, making them masturbate in front of him.

“Yes, there were allegations dating back to the 1970s” against Fitzmaurice, Murphy says. “However, when the accused member is deceased, and the abuse is said to have happened decades ago, there is a challenge in doing an investigation that is adequate for determining whether or not the allegation is substantiated.”

Other Catholic orders and dioceses have done so, though, under similar circumstances.

Checks are made on current Benedictine members, Murphy says: “The abbey does perform an internal review of the files of current members to ensure those in ministry are fit for ministry.”

He also says, “We will be updating our website within the next couple of weeks to include our policy that, when an allegation has been substantiated against a monk, his name will be published on the website.”

The Marmion Abbey won’t provide information on accused members, past or present.

That includes Charron, the monk charged earlier this year with sexually abusing a student.

After his arrest, the abbey posted Charron’s $30,000 bail.

Marmion maintains no public list of credibly accused clergy members.

Nor does St. Benedict’s, though one is in the works. It’s expected to include fewer than 10 names, with Chmura the only one living, according to the Rev. Benedict Neenan, the abbot of the Conception Abbey in Missouri, which now oversees St. Benedict’s.

In the past few years, Neenan also created a public list for Conception.

“I agreed, when I became abbot about six years ago, that transparency was better for us than stonewalling,” Neenan says. “Even though you take the blows at the beginning, in the long haul, it’d be better for everybody.”

Prayer first, then perhaps transparency

The Benedictine abbey running St. Bede’s Academy, about 90 minutes south of Chicago, offers no such public accounting.

A monk there, the Rev. Samuel Pusateri, was convicted in the 1990s of molesting a student and sentenced to six years in prison, records show.

After he completed his sentence, church records show he was a chaplain for a group of nuns in Wheaton from 1995 to 2004.

At some point, he also lived in a Benedictine community in Italy. The order won’t say where he’s now living except that it “is in a highly supervised setting with a safety plan in place.”

The Rev. Michael Calhoun, the St. Bede’s abbot, says, “St. Bede Abbey and Academy takes very seriously our commitment to safeguarding all entrusted to our care” and has “a policy of zero tolerance for sexual misconduct of any sort.”

Recently named abbot, he says he has “not yet had the opportunity to consider publishing a list. I would need to take additional time to pray and reflect before making the decision.”

READ MORE