Kiwi carpet-maker Bremworth will today announce new 10-year supply contracts to provide its farmers with certainty – and the agriculture minister is calling on government agencies to look favourably on NZ wool carpets

It was Toby Williams' great-great-grandfather who first ran sheep on their rugged East Coast hills – and if it's what they want, Williams would love his two sons to follow in the family footsteps.

But it costs more to shear sheep than farmers can make from selling the wool. Many sheep farmers are already turning over their farms to plantation forestry, for the carbon credits. Others are using short-wool Wiltshire rams to breed the wool off their Romney flocks, to farm only for meat – though even that price has plummeted from last year's peak of nearly $10/kg to just $6.75/kg.

The flock number has fallen from more than 70 million in the 1980s to just 25 million today. Farmers are asking whether they're seeing the death of the industry that once made New Zealand famous. "That's codswallop," the agriculture minister retorted angrily to one robust inquisitor, yesterday.

READ MORE: * The Detail podcast: The woes of wool * Farmers look to ride on the sheep's back again * Heat on agriculture over $150m in mandatory levies

But Williams, the chair of the Meat and Wool Council for Federated Farmers, is pessimistic: "I think within 12 months, unless we get long-term meaningful contracts for our wool from customers, then we're going to struggle to have an industry that is viable at scale."

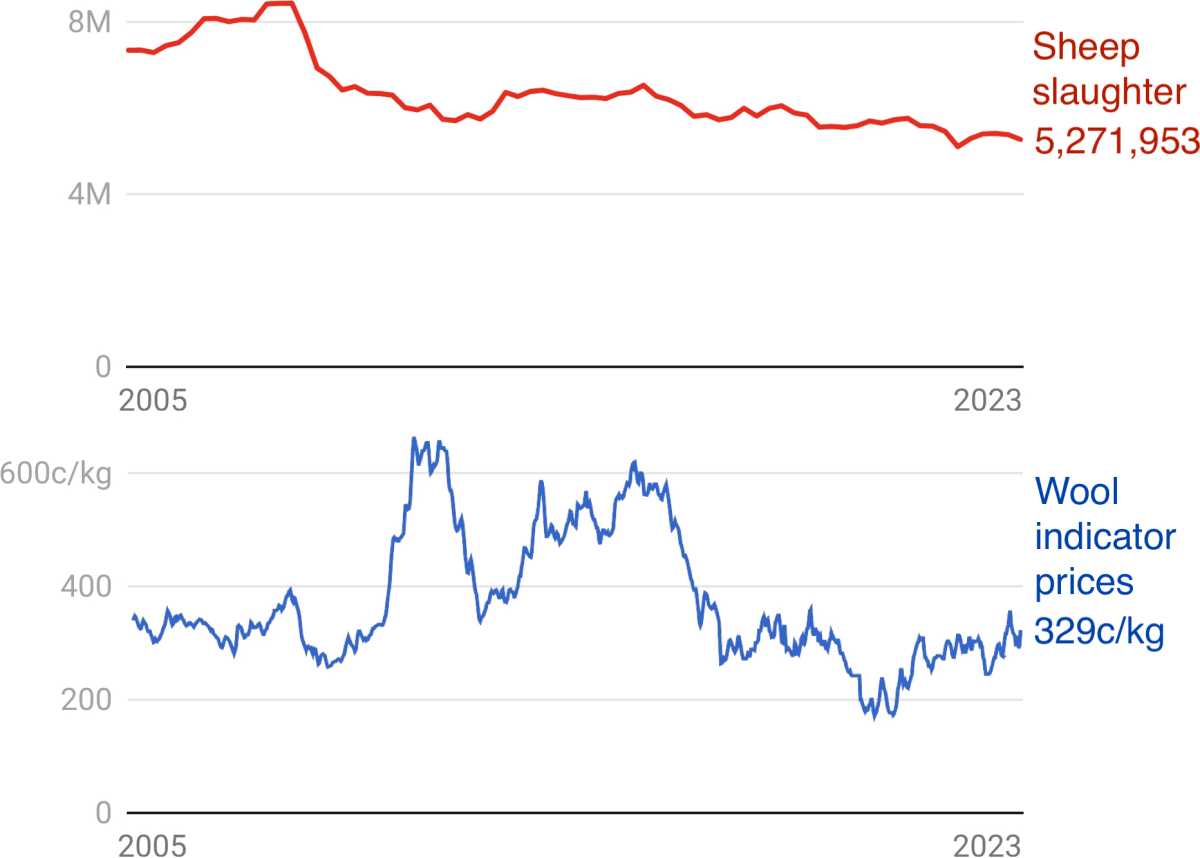

This week, Stats NZ published grim figures showing the rapid decline in numbers of sheep sent to slaughter: from 40 million a year in the late 1980s, to 21 million this past year.

And Beef + Lamb NZ published its annual report, documenting a "disappointing" decline in lamb and hogget prices, and continuing poor returns from wool. "Uncertainty around government policy decisions and their impact on the sheep and beef industry continued to influence farmer decisions and farmer morale was at very low levels," it said.

"The pace of change in the regulatory area has not slowed as the general election approaches. Farmers were wearied by the continuing deluge of bureaucracy," the report says.

The fightback starts today. Speaking to Newsroom, Agriculture Minister Damien O'Connor is calling on government agencies to factor in New Zealand-sourcing and sustainability to their procurement decisions.

He cites the Ministry of Education's decision to carpet nearly 800 schools with synthetic US carpet, instead of New Zealand wool carpet.

It should be "a basic requirement" that government departments place greater weight on the sustainable attributes of natural fibres like wool and wood, and the fact that it's farmed in New Zealand. "This is an indigenous, homegrown, biodegradable, renewable product that has arguably better value in a classroom than its nylon alternative," he says.

And Auckland-based Bremworth NZ, which buys about 3 percent of New Zealand farmers' wool, will today announce new 10-year supply contracts, to provide its farmers with certainty of income.

The company, which makes exclusively woollen carpets from yarn-spinning plants in Napier and Whanganui, and a carpet-tufting factory in Auckland, is headed by Greg Smith. He was previously chief executive of merino outdoor attire company Icebreaker, when it offered its fine wool suppliers 10-year contracts in 2017.

Now, he tells Newsroom he'll be offering a similar deal to rough wool farmers, so long as they comply with quality specifications and certifications such as the New Zealand Farm Assurance Programme.

The moves are welcomed by Toby Williams. He doesn't blame the Government for the woes of sheep and wool farming – he says that's on the industry, for its own dearth of leadership since abolishing its representative wool levy body in 2009.

He's glad of the Government's investment in the wool sector, but says it needs to be better targeted. At present, he says, organisations like Wools of NZ show few results and little accountability for how they're spending public money.

As for Bremworth's long-term contracts, he says it's the best step forward for wool farmers in years.

"I'm glad of the leadership they're showing, and we need other wool-buyers to follow that lead. What they are doing is they're securing their supply, into the future."

Other organisations tasked with commercialising wool, like Wools of New Zealand and Wool Impact Ltd, have failed or refused to offer contracts, he says.

"Bremworth have looked and gone, crikey, for us to survive and be a business we need surety of supply. The only way to get surety of supply is to offer farmers a contract."

Williams sees others turning over their hill-country farms to pine plantations, but he's adamant he won't follow their lead. He's done the numbers: he reckons he will makes $4.5m over the next 16 years from farming sheep and beef; conservatively, he would make $40m from farming carbon credits.

"The potential returns you can get as an investor far and away outstrip anything you could get from a sheep and beef farmer perspective," he says.

"I'd have got 40 million bucks in the bank, and I'd be sitting on a beach in Fiji somewhere. But my staff and their jobs would be gone, the million dollars a year I spend in town would be gone, the businesses that I support in town would have less jobs, and they'd be hiring less people.

"Forestry destroys communities. Have a look at the East Coast where I live. In the 1980s when we put in all this forestry, that was the death knell of all these communities. It really was the straw that broke the camel's back.

"Banks, post offices, bike shops, saddleries, all those things, there's lots of things gone. The wholesale planting of forestry – I'm not saying it was the wrong thing, but we don't see the jobs that are associated with sheep and beef farming."

He describes carbon farming as "a government-backed ponzi scheme", that will eventually collapse when industry has made sufficient emissions reductions that it no longer needs to buy carbon units.

And he's not tempted by the cash. "It could be $100 million, and I wouldn't do it. I love what I do. I've got an incredible property that I love, our family have been here for 130 years, and I just don't trust the carbon farming scheme.

"We've got an incredible legacy on this property. It's a very special piece of dirt and they don't make more dirt. Yes, we could put pine trees all over it. We've already seen what the after-effects of that has been with the cyclones in our region. Planting trees is a knee-jerk reaction – what we really need to do is stop pulling fossil fuels out of the ground and burning them.

"If somebody funded me to put more natives into my property, then we'd be all over it. We'd put in another couple of 100 hectares of natives, easy."