Baldur's Gate 3 is an exceptional game: a grognardy CRPG with complex and barely-explained D&D rules and a massive mainstream success, even before its console releases. With Diablo 4's always-online grind providing the perfect contrast, it's come across to some as a victory over malignant modern videogame trends: Where other companies build cosmetics stores and battle passes, Larian Studios has succeeded through good old fashioned respect for player freedom, ambition, and quality craftwork, or so go some popular posts and articles.

A handful of game developers, meanwhile, have cautioned against oversimplifying the lesson, arguing that Baldur's Gate 3 is an anomaly that even big studios won't be able to replicate. Online arguing has ensued.

In an interview with PC Gamer earlier this week, Larian founder Swen Vincke weighed in on the debate, which he finds somewhat perplexing. It's a given that not any studio could make Baldur's Gate 3, he said, but he questions the importance of videogame "standards," which he says "die every day" as new ideas emerge and old one are reinvented.

Backing up to the start, this conversation coalesced in large part around a Twitter thread by game designer (and former PC Gamer contributor) Xalavier Nelson Jr, who sought to "gently, pre-emptively push back against players" who would use their excitement for Baldur's Gate 3 to "apply criticism or a 'raised standard' to RPGs going forward." His argument was that Baldur's Gate 3 isn't a schema that any RPG developer can work to, but the product of a particular developer taking a huge risk under a particular set of circumstances.

"In an era of megagames, Baldur's Gate 3 is one of the largest attempted, built by a specialized group of people using mature tech specially built to make *this specific game*, reinforced by invaluable mass player feedback AND market validation ahead of its launch," wrote Nelson. "This is not a new baseline for RPGs—this is an anomaly. Trying to do the same thing in the same way, especially without the same advantages, could kill an entire GROUP of studios."

Responding to the thread, Obsidian designer Josh Sawyer agreed that "the conditions under which BG3 was made are atypical," as did Diablo 4 senior designer Chris Balser, who said that "people too often only look at the fruits of labour and not the labour itself." On the flipside, a lot of gamers read these cautions against rising expectations as defensive. Why not expect more from RPGs after a developer has successfully pushed the genre's boundaries in a direction we like?

Asked about the debate, Vincke agreed that Baldur's Gate 3 could only have come about under certain circumstances—"obviously, yeah, if you're a 50 man studio or 10 man studio, you shouldn't try to make a game like BG3," he said—but he questioned the reality of the "standards" being argued over.

There's always been innovation, but at the same time, it doesn't require massive technological evolution to do something crazy, and cool, and different than what anybody else has done before.

Swen Vincke

"The problem I have is with the use of the word 'standards,'" Vincke said. "This is videogames, standards just die every day. Things get reinvented. New things appear all the time. When I was starting out in the industry, Assassin's Creed set the new standard. It was over—nobody could make games like Assassin's Creed, there was too much budget behind it, that was going to be the future, everybody had to consolidate, blah blah blah. That didn't materialize. In videogames there's so much free space to explore, still, in the creative tree."

To the extent that standards do exist, Vincke found it "strange" that developers from larger studios would be concerned about boundary-pushing, pointing specifically to the new creative possibilities that technological advancements can enable. As for RPGs in particular, he noted that it doesn't take an enormous game like Baldur's Gate 3 to change the genre.

"Disco Elysium changed standards on the fly with a small team, right?" said Vincke. "That's a completely different standard now. There are so many games that change standards, to the point that there's no standards, was my thing. But I think you should always strive to evolve, especially in this medium which is different than other media in the sense that technological evolution has always been a big part of it. There's always been innovation, but at the same time, it doesn't require massive technological evolution to do something crazy, and cool, and different than what anybody else has done before."

The disagreements here may come down to mismatched premises. Audience expectations obviously evolve as games evolve, and any argument that gamers shouldn't want or expect high quality games is easy to reject. "I'm not saying that at all," said Nelson in a video follow-up to his Twitter thread. Rather, the designer meant that no amount of investment can guarantee a good, hit game, which made Baldur's Gate 3 a tremendous risk to develop, and attempts to replicate it under different circumstances very likely to fail. We have seen that kind of thing happen in the past, like when EA set a very successful developer, BioWare, on building an answer to Destiny 2, and it totally flopped.

A lot of folks had questions and concerns as a result of my earlier Baldur’s Gate 3 thread……So, I’m happy to keep talking about the really complex, interesting realities of megagame development today and clarify some points via video! 😁 pic.twitter.com/NKktawOGuVJuly 15, 2023

But if the best aspects of Larian's approach do rub off on other RPG projects, even in small ways, I certainly won't be disappointed. And if studios with lots of money are going to invest it in big risky projects, I can think of worse things for them to fail at than intricate, systems-driven RPGs, especially if those RPGs store my save files on my damn PC instead of a server somewhere to keep me from bypassing a cosmetics shop—so I only follow the argument so far myself. Gamers aren't speaking as industry executives when they say that Baldur's Gate 3 raises the bar, just as people who'd like to see more of this kind of thing. I don't think anyone means that every future RPG ought to surpass Baldur's Gate 3's size and complexity.

The rallying cries that tend to rise to the top of social media do leave out a lot of reality, though. For one thing, I'm not sure the games industry has been proven wrong in any meaningful way here in the first place. People do like live service games—unless we pretend everyone who plays Destiny 2 is being manipulated by mind flayer tadpoles—and you don't even have to look away from the mainstream to find that big singleplayer RPGs never went away. Starfield releases next month! And when we do turn just one degree towards smaller publishers and developers, I can start naming excellent, non-live servicey games until I run out of breath, even if I stick to recent releases: Wartales, Tchia, Remnant 2, Dave the Diver, Amnesia: The Bunker…

Hell, ultra-nerdy CRPGs didn't even go away: If the success of Baldur's Gate 3 is just down to an old-school philosophy, then where's the 800,000 concurrents for the Pillars of Eternity and Wasteland games? So of course there's more to it than 'Larian just went and made a good game.' Vincke himself was afraid the launch would be a bust right up until it wasn't.

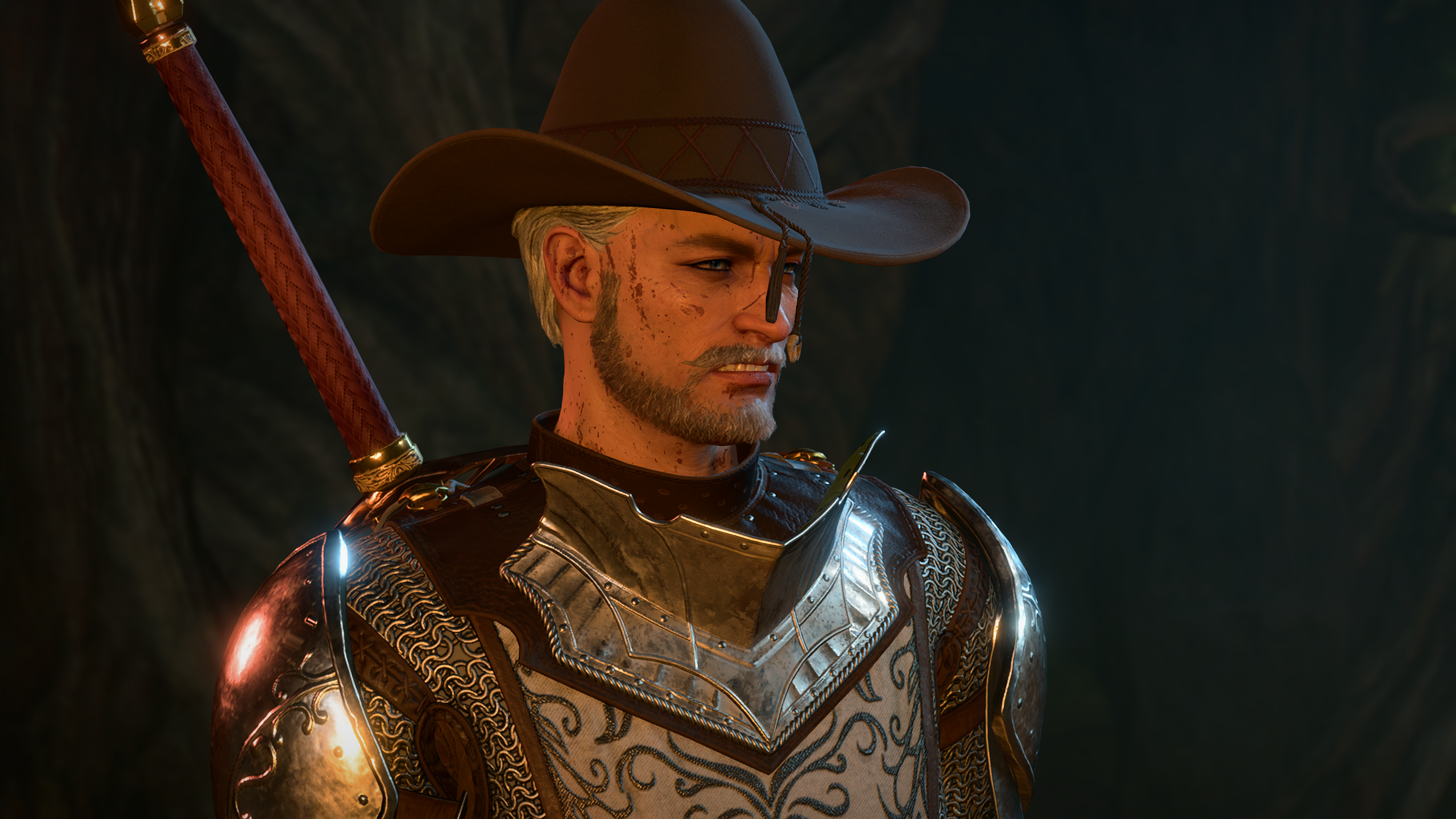

It also isn't true that Larian totally rejected modern trends: The tone of Baldur's Gate 3 is contemporary, reminiscent of the extremely popular Critical Role D&D streamers and other tabletop broadcasters (and to a lesser extent the recent D&D movie), it's indulgent with its sex and romance, and the technical quality of its graphics is a few bars higher than that of Larian's last big RPG, Divinity: Original Sin 2. That game was our 2017 Game of the Year, but not quite the mainstream hit that Baldur's Gate 3 has been, and I feel pretty confident in saying that the sexier, nuder companion rendering has had some part to play in that.

Not that I'm against sexy, nude RPG characters, but if you want to argue about that, allow me to direct you to my brave pals Fraser and Robin.