Scientists may finally know what made the largest explosion in the universe ever seen by humankind so powerful.

Astronomers have discovered that the brightest gamma-ray burst (GRB) ever seen had a unique jet structure and was dragging an unusually large amount of stellar material along with it.

This might explain the extreme properties of the burst, believed to have been launched when a massive star located around 2.4 billion light-years from Earth in the direction of the constellation Sagitta underwent total gravitational collapse to birth a black hole, as well as why its afterglow persisted for so long.

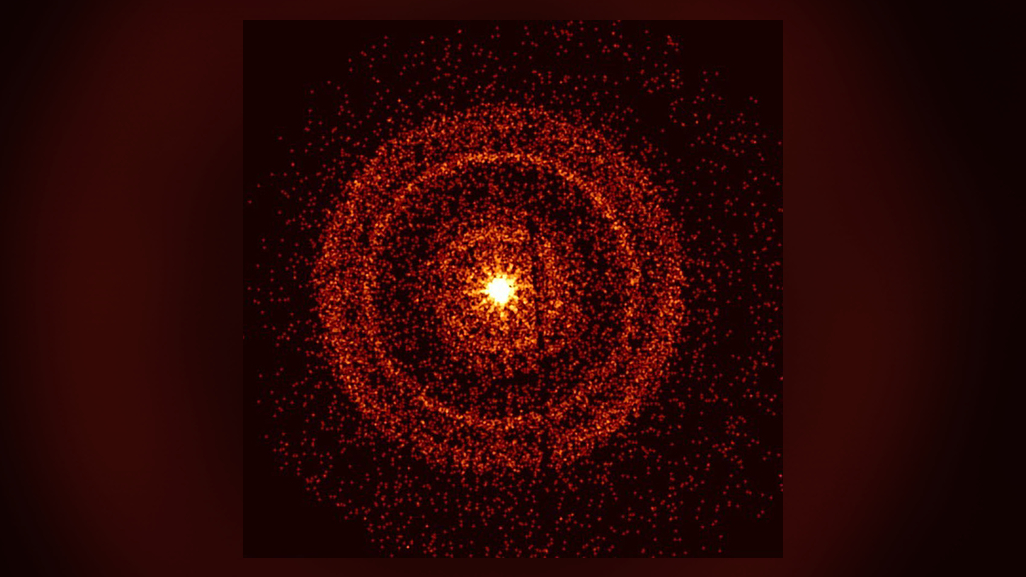

The GRB officially designated GRB 221009A but nicknamed the BOAT, or the brightest of all time, was spotted on October 9, 2022, and stood out from other GRBs due to its extreme nature. It was seen as an immensely bright flash of high-energy gamma-rays, followed by a low-fading afterglow across many wavelengths of light.

Related: Brightest gamma-ray burst ever detected defies explanation

"GRB 221009A represents a massive step forward in our understanding of gamma-ray bursts and demonstrates that the most extreme explosions do not obey the standard physics assumed for garden variety gamma-ray bursts," George Washington University researcher and study lead author Brendan O'Connor said in a statement. O'Connor led a team that continued to monitor the BOAT GRB with the Gemini South Telescope in Chile following its initial discovery in Oct 2023.

Northwestern University doctoral candidate Jillian Rastinejad, who was also part of a team that observed the BOAT on Oct. 14 after its initial discovery, told Live Science that GRB 221009A is thought to be brighter than other highly energetic GRBs by a factor of at least 10.

"Photons have been detected from this GRB that has more energy than the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) produces," she said.

Even before the BOAT was spotted, GRBs were already considered the most powerful, violent, and energetic explosions in the universe, capable of blasting out as much energy in a matter of seconds as the sun will produce over its entire around ten billion-year lifetime. There are two types of these blasts, long-duration, and short-duration, which might have different launch mechanisms, both resulting in the creation of a black hole.

Further examination of the powerful GRB has revealed that it is unique for its structure as well as its brightness. The GRB was surprisingly wide. So wide, in fact, that astronomers were initially unable to see its edges.

"Our work clearly shows that the GRB had a unique structure, with observations gradually revealing a narrow jet embedded within a wider gas outflow where an isolated jet would normally be expected," co-author and Department of Physics at the University of Bath scientist Hendrik Van Eerten said in a statement.

Thus, the jet of GRB 221009A appears to possess both wide and narrow "wings" that differentiate it from the jets of other GRBs. This could explain why the afterglow of the BOAT continued to be seen by astronomers in multiple wavelengths for months after its initial discovery.

Van Eerten and the team have a theory as to what gives the jet of the BOAT its unique structure.

"GRB jets need to go through the collapsing star in which they are formed," he said. "What we think made the difference in this case was the amount of mixing that happened between the stellar material and the jet, such that shock-heated gas kept appearing in our line of sight all the way up to the point that any characteristic jet signature would have been lost in the overall emission from the afterglow."

Van Eerten also points out the findings could help understand not just the BOAT but also other incredibly bright GRBs.

"GRB 221009A might be the equivalent of the Rosetta stone of long GRBs, forcing us to revise our standard theories of how relativistic outflows are formed in collapsing massive stars," O'Connor added.

The discovery will potentially lay the foundation for future research into GRBs as scientists attempt to unlock the mysteries still surrounding these powerful bursts of energy. The findings could also help physicists better model the structure of GRB jets.

"For a long time, we have thought about jets as being shaped like ice cream cones," study co-author and George Washington University associate professor of physics Alexander van der Horst said. "However, some gamma-ray bursts in recent years, and in particular the work presented here, show that we need more complex models and detailed computer simulations of gamma-ray burst jets."

The team's research is detailed in a paper published in the journal Science Advances.

Originally posted on Space.com.