The case for Martian volcanoes soaring above ancient, vanished oceans keeps getting stronger.

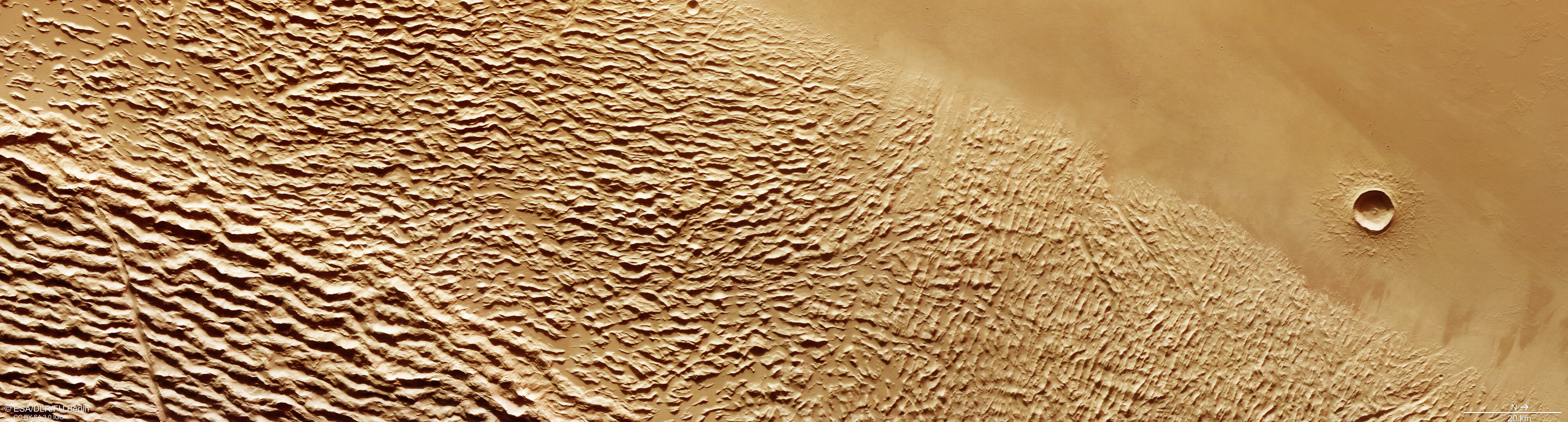

Researchers analyzing images of Mars' Olympus Mons, the tallest volcano in our solar system, say a wrinkled patch of land near the mountain's northern region likely formed when blisteringly hot lava oozed out of the summit millions of years ago. That lava is thought to have run into ice and water at the mountain's base, resulting in landslides. At least a few of these landslides must have stretched about 621 miles (1000 km) from the volcano and wrinkled as they hardened across eons, scientists say.

While such streaked features on Mars have been long-studied, however, the role of water in their formation has remained an open question. The new findings add evidence to the prevailing theory that liquid water once flowed freely on the Red Planet, which is now a frigid desert world except for remnant ice largely locked within its poles.

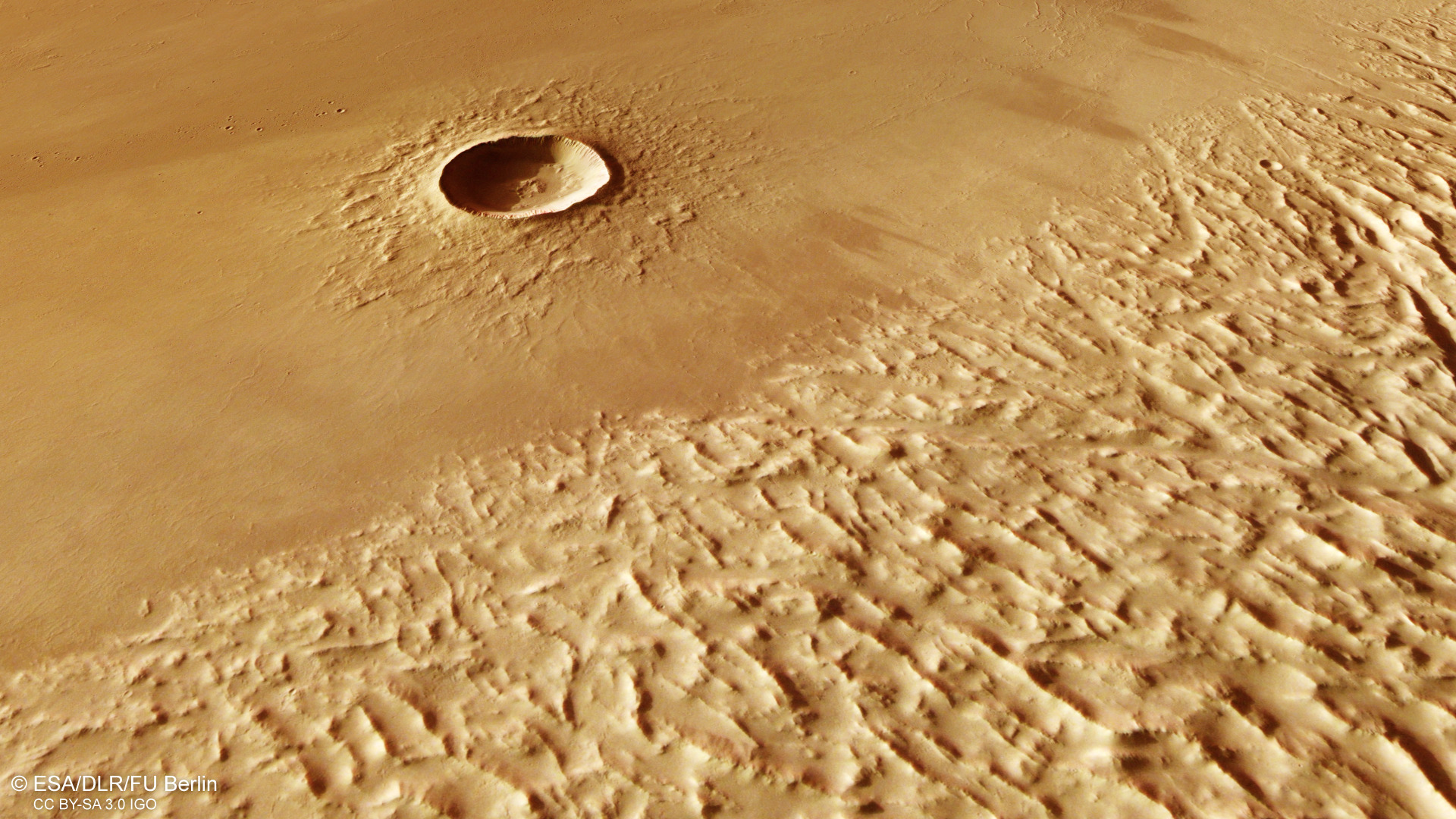

The crumpled patch of land featured in the new images is known as Lycus Sulci (Sulci is a geologic term; Latin for parallel grooves). It was snapped in January of this year by the European Space Agency's Mars Express orbiter, which celebrated two decades of circling Mars while searching for signs of underground water.

Related: We could start a settlement on Mars with just 22 people, scientists say

These new insights arrive on the heels of similar geological evidence found in July regarding gigantic cliffs surrounding Olympus Mons. Researchers believe those cliffs, or escarpments as they're called, mark an ancient shoreline inside of which lies a large depression where liquid water once swirled. The latest results support that idea, suggesting the lower part of the mountain crumbled when ice and water at its base became unstable upon encountering lava exuded from its insides.

"This collapse came in the form of huge rockfalls and landslides, which slipped downwards and spread widely across the surrounding plains," researchers wrote in a statement.

Lycus Sulci, featured in the new images, stretches for 621 miles (1,000 km) from Olympus Mons and stops just short of reaching the Yelwa Crater, a 4.9 mile (8 km) Martian bowl named after a town in Nigeria.

The grooves that mark lava flows near the Yelwa Crater show "just how far the destructive landslides traveled from the volcano's flanks before settling," researchers said in the same statement.

Although a tantalizing possibility, the new results do not conclude whether the Lycus Sulci region was friendly toward life on Mars. On Earth, however, a first-of-its-kind research study from 2019 showed that "lava crickets" in Hawaii are skilled at thriving in the scorching, unforgiving heat of the lava that follows volcanic eruptions.

While the presence of liquid water in Mars' past is good news for life in general, scientists think any living organisms that may have thrived on a once watery Mars perished along with the oceans. Few others suggest single-celled organisms may have managed to hibernate deep inside the planet's ice caps, although if they're still around today is anybody's guess.