Notes on the best illustrated coffee-table book of the year by miles

I was moping around the Auckland Art Gallery a few months ago, stuck in the galleries of the colonial past, bored to sobs with the densely oiled landscapes with no one in them (that old message of white rule: we can take this land because it's empty), even more bored by the dark and serious portraits of the stuffed shirts who filled important civic posts - I wasn't feeling it, everything and everyone looked remote, distant, stiff. I hate the past. The past is another cemetery, everyone's dead in it. But then I came across a portrait of a 19th Century Māori chief - never heard of him, or the artist - and the guy looked completely alive, which is to say he looked completely present. It was a wonderfully dislocating moment. I don't know what it was about him, an expression maybe, a kind of vitality, perhaps it was the strength of his straight-up mana, but his portrait did that thing we use a cliché to describe but is actually thrilling to experience: he stepped out of the past. He was recognisable, intimate.

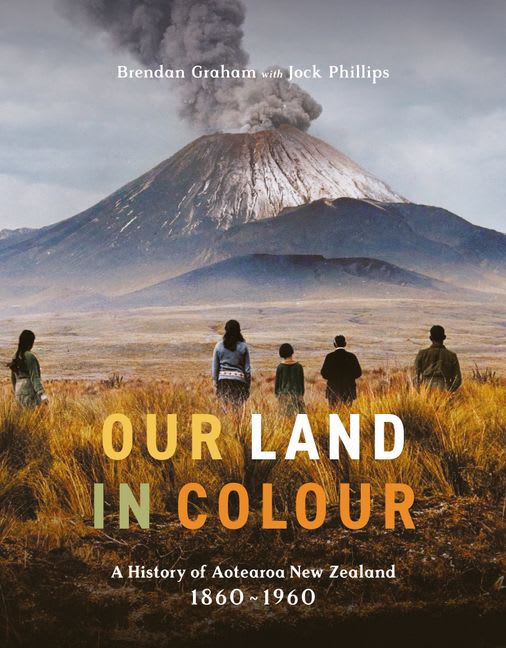

There's a similar very pleasing sensation in the pages of a new illustrated coffee-table book Our Land in Colour: A history of Aotearoa New Zealand 1860-1960, a collection of more than 200 old black and white photographs colourised by Wellington digital colourist Brendan Graham. It's the past, but a lot of it looks as fresh as the present. It's one of the best-selling books of the year and I'm pretty sure it's also the best illustrated coffee-table book of the year.

Jock Phillips writes in the Introduction, "It [colourising] makes immediate the very different ways New Zealanders experienced life for a century." But the only difference, the only signs of ancient experience, in the photo (below) of workers harvesting kūmara over 100 years ago, in Northland, are the clothes and the use of a horse-drawn plough. A whole section in Our Land in Colour is devoted to work (other sections include the suburbs, leisure, and war). Good idea. The daily chore is one of life's constants. You can feel the Northland dirt, sense the sweat and labour and long hours - but you can also sense a family, a togetherness. The baby on the girl's lap, the other teenager leaning into her spade - I'm guessing sisters, or cousins, not sure about the guy in the hat, though. It's been a good day's work - the girl with the baby is sitting on a full sack of kūmara - but what's the bigger picture, of land and colonisation and subsistence poverty? The hills are bare with logging and my guess is that the Māori harvesters aren't going to see a cent of it.

I suppose my life as a bookman kind of began when I was 24 and met the founding publisher at Victoria University Press, Pamela Tomlinson, and offered to chop her firewood in return for free books. I liked chopping wood anyway and I liked Pamela, too, who died young, and was replaced by her assistant, an amiable young fellow in sandals called Fergus Barrowman. The books she gave me included the short story collection The Shirt Factory by Ian Wedde, which I loved, and also an illustrated study of Rua Kenana, Rua and the Maori Millennium by Peter Webster, which blew my mind. "In the heart of the Urewera ranges, there is a great clearing in the forest, and scattered over it the empty houses of a departed people ... these are remains of the once thriving settlement of Maungapohatu. Here, at the beginning of this century, the prophet Rua Kenana led his people to found a New Jerusalem in the wildnerness. In the shadow of a sacred mountain, over a thousand of Rua's followers sought to escape the European settlers and live free from the domination of an alien race." I'd never heard of Rua, never knew his amazing story; and yet, only now, in the pages of Our Land of Colour, can I see him (below). He looks as mesmerising now as he surely was then, just as fervent, just as really quite beautiful.

1/2C008873F, James McDonald

"That's a great photo," said Vincent O'Sullivan, when I sent him the picture of a guard and prisoner at the POW camp in Featherston, in 1943 (below). That same year, 48 prisoners were shot dead. O'Sullivan wrote a play, Shuriken, which examined the tragedy. "When I was getting background stuff for Shuriken it was still in time to meet several of the guards, as well as some of the Japanese prisoners who were on a kind of 'old boys' tour to Featherston. Some great stories from both sides. It seems the Māori guards and the Japanese got on particularly well. One story I liked was one February day, very hot, a few guards and a consignment of prisoners were down at the river, detailed to pack sandbags. One guard said too hot for this caper, the soldiers propped their rifles on the bank, and then all of them swam in the river together for a break. I love it that it could even happen, with clearly a sense of trust on both sides."

"Colourising," writes the book's author, Wellington digital colourist Brendan Graham, "helps to transport us back in time and give us a sense of what life may have been like in the past." This is 100 percent correct but the sense you get in the 1930s photo below is something kind of excruciating. It's like a parable of race relations, of blindness and good intentions, of weakness and privilege. Look at the distance the Māori are keeping from the do-gooders. Look at their clothes! Everyone in the family are barefoot, while the Pākehā wear leather shoes and look trim, tucked-in, belted, in their sensible and likely not inexpensive woollens. The look on the little kid's face at right speaks to a century of the New Zealand experience.

There are pictures of gum diggers, of trams, of auto assembly lines, of ballroom dancing, of the public bar, of free milk in schools....The target market is old people but Our Land in Colour is a hit for any age. Great book, recommended.

Our Land in Colour: A History of Aotearoa New Zealand 1860-1960 by Brendan Graham with Jock Phillips (HarperCollins, $55) is available in bookstores nationwide.