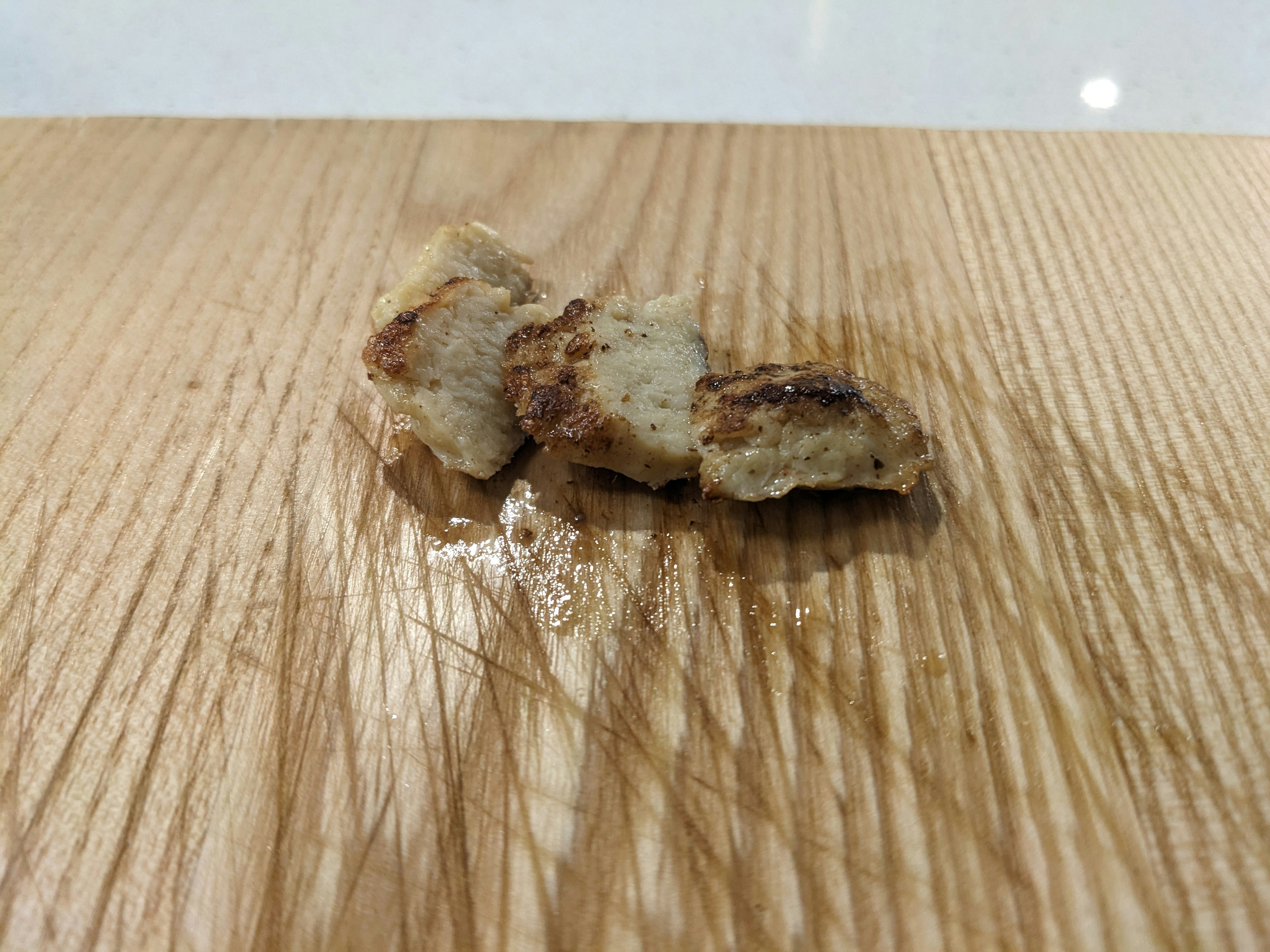

I’m in the kitchen of a tech lab munching on a morsel of chicken around the size of a Frosted Mini-Wheat. The small chunks of meat sit among plum tomatoes, thinly-sliced onions, a few capers, and a butter-based sauce.

I take a bite and the flavor is savory and somewhat familiar. It tastes like chicken, to use an old cliche, but it doesn’t necessarily feel like chicken. The meat has a texture that can be categorized somewhere between fish and dark meat poultry.

But here’s the thing — it is chicken. Just not the kind you’re used to.

I sampled meat made out of chicken cells grown in a vat that resembles the machinery at a dairy factory. The outcome: chicken meat that never actually clucked as a fully grown chicken.

This futuristic morsel of a meal was prepared for me by Daniel Davila, a chef-turned-senior food scientist at UPSIDE Foods, a company that’s producing cell-cultured meats (which are also referred to as cultivated or lab-grown).

As the name implies, there’s no slaughterhouse involved. Instead, the company takes cells from an animal and replicates them in a controlled environment with the help of a nutritive slurry. The outcome: a cut of, well, meat?

“I can have that delicious meat experience in a way that is more sustainable for the planet.”

It’s a middle step between industrial meat production — which comes with a host of issues, namely environmental and ethical — and the fleet of fake meats peddled by companies like Impossible Burger.

“Our vision of having impact is that we create a product that is as versatile and flexible as the conventional meat analog,” Amy Chen, chief operating officer of UPSIDE Foods, tells me just before my tasting, referring to the faux, often soy-based chickens and beefs (and even crabcakes) of the vegan and vegetarian world.

“That I believe is what's going to unlock the impact that we want to have — when consumers say … I can have that delicious meat experience in a way that is more sustainable for the planet and that doesn't require animals to be slaughtered in the process.”

Cruelty-free flesh?

It’s a noble goal shared by a few dozen companies working on similar projects. Some, like Good MEAT, even operate a few miles from UPSIDE’s production facility in California’s Bay Area.

Finless Foods also operates nearby, with the goal of hawking lab-grown fish. It isn’t the only fake-fish grower — there’s also Wildtype, based in nearby San Francisco, and BlueNalu, based in San Diego.

But UPSIDE currently has a crucial upper hand: In November, the company became the first of its kind to receive a “pre-market consultation” from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. This means the agency had “no further questions” about the safety of UPSIDE’s process. But this lab-grown meat isn’t quite shelf-ready. It still faces a few more regulatory hurdles: The Department of Agriculture needs to inspect UPSIDE’s facilities, along with the product itself.

The meat-printing process

The precise methods UPSIDE uses to turn cells into appetizing meat is proprietary, but a document submitted to the FDA reveals some key details.

First, the company extracts and analyzes cells from parts of chickens that we already eat, including muscle and skin tissue. These cells come from animals bred for meat production. The cells are then analyzed to make sure they’re stable enough to reproduce over and over and produce quality tissue. The winners are banked for use and engineered to delay further growth.

The cells then receive a nutritive slurry that “consists of common compounds found in animal feed and human food including amino acids, fatty acids, sugars, trace elements, salts, and vitamins,” according to the company’s filings.

In a sealed steel vessel, cells divide similarly to those in an animal embryo. The result is “integral tissue” — the mysterious lab-grown meat. The grub is then washed and dried out “to render them most suitable for consumer product formulation.” Yum!

Battle of the proteins

Should we ditch the real thing for lab-grown chicken and beef? The faux morsels could offer some distinct advantages.

For example, cultured meat could prove safer because it’s less likely to be contaminated by potentially dangerous substances like E. coli bacteria, which comes from improper exposure to intestinal pathogens, according to a 2020 review paper published in Frontiers in Nutrition. These high-tech facilities also won’t have to deal with risks like the avian flu outbreak that swept multiple facilities in the United States, infected 57 million birds, and drove up poultry costs.

But when it comes to environmental impacts, it’s hard to declare a winner. For instance, livestock contribute around 14 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. Cows burp out lots of methane, which has more than 80 times the warming effect of carbon dioxide. In fact, global methane emissions could increase by around 40 percent by 2050 due to rising food production.

Meanwhile, cultured meat production may produce a comparatively larger share of carbon dioxide, which lingers in the atmosphere longer than methane — depending on the type of energy used to power the facilities.

There’s also the matter of consumer preference.

The review paper also mentions possible economic devastation to rural communities if livestock production shut down, as well as unintended land consequences. “Livestock plays a key role in maintaining soil carbon content and soil fertility, as manure from livestock is a source of organic matter, nitrogen, and phosphorus,” the authors write.

Plus, companies will need to pay close attention to their cells in the lab, the paper notes. Rapid cell growth could have unforeseen impacts on muscle structure and potentially on the health of consumers. And it isn’t guaranteed that the mix of nutrients put into lab-grown meat will be as comprehensive as those in the real thing.

There’s also the matter of consumer preference. A paper published last year in Food Quality and Preference signaled that 50 percent of respondents in Australia wouldn’t eat lab-grown chicken and 49 percent would decline to taste lab-grown beef.

Two-thirds of American consumers surveyed in a 2017 PLoS One study showed a willingness to try it, but only one-third said they’d make it a dietary staple.

So the market may be there, but it likely won’t become a massive hit — of course, it needs to reach store shelves first.

My verdict

So how was this near-mythical chicken? It was … decent. Davila prepared it well, and the texture was close but slightly uncanny. To ensure journalistic rigor, I also tried a grilled chicken breast sandwich at a nearby diner after my tour.

One last thing: I was weirdly gassy the rest of the day. While this isn't abnormal for me, and it's impossible to draw a direct connection between my bloating and the lab-grown meat without further tastings, I had to mention it.

Would I be willing to try it again? Probably. As a conflicted omnivore, it might be good to have a nearly guilt-free alternative, even if you can’t grow an entire chicken wing in a lab quite yet.

This product, along with the range of cellular protein creations now in the works, has plenty of testing ahead of it. But all in all, it sure could make In-N-Out trips or celebratory steak dinners feel less conflicting.