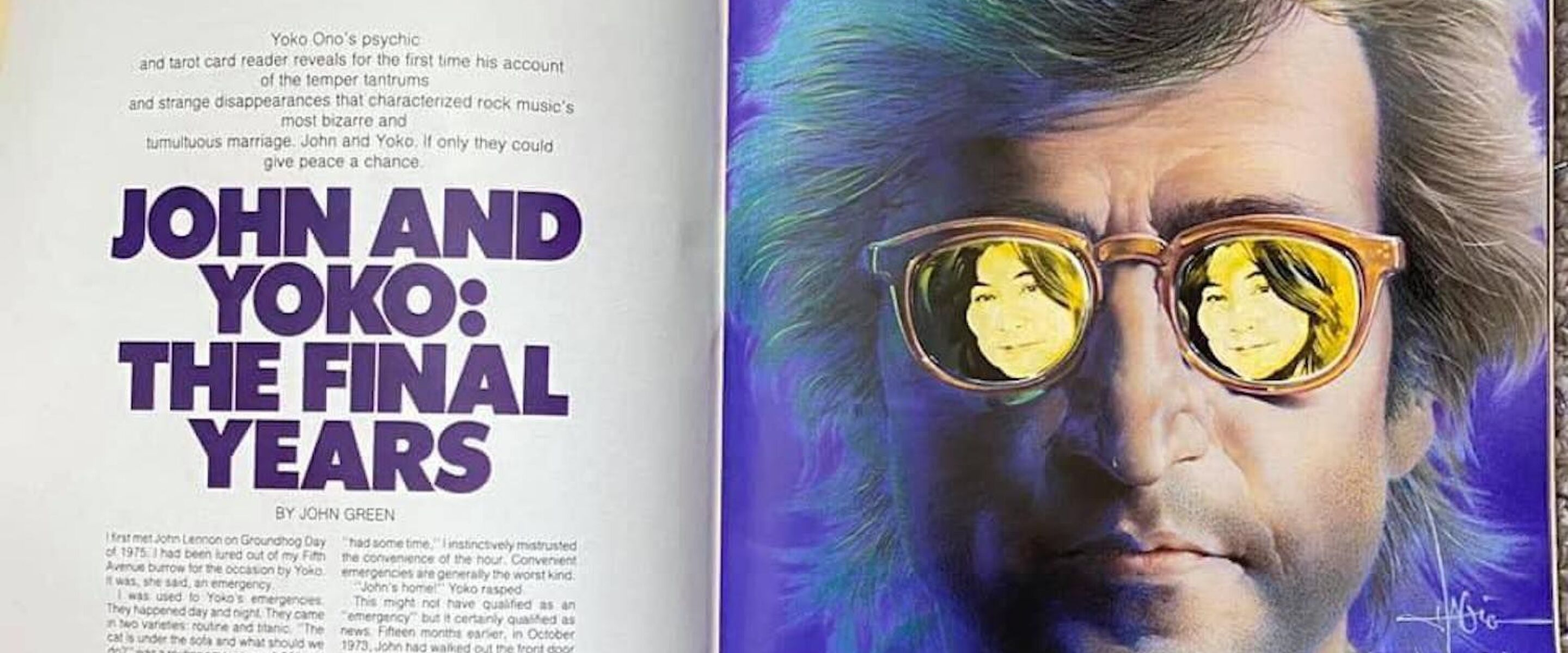

Kunio Hagio’s poster art for “Raging Bull” smolders with a ferocity that could make a boxer facing such an opponent want to flee the ring.

Using oil paint, pencils and an airbrush, he created a sweat-drenched, bruised, hyper-realistic portrait of Robert De Niro as boxer Jake LaMotta that conveys a battered pugilist stalking his prey.

His painting for the 1980 Martin Scorsese film became one of the most recognized images in cinematic history.

Mr. Hagio, 74, who had heart and lung problems, died in his sleep May 8 in Arizona, where the Skokie native moved years ago.

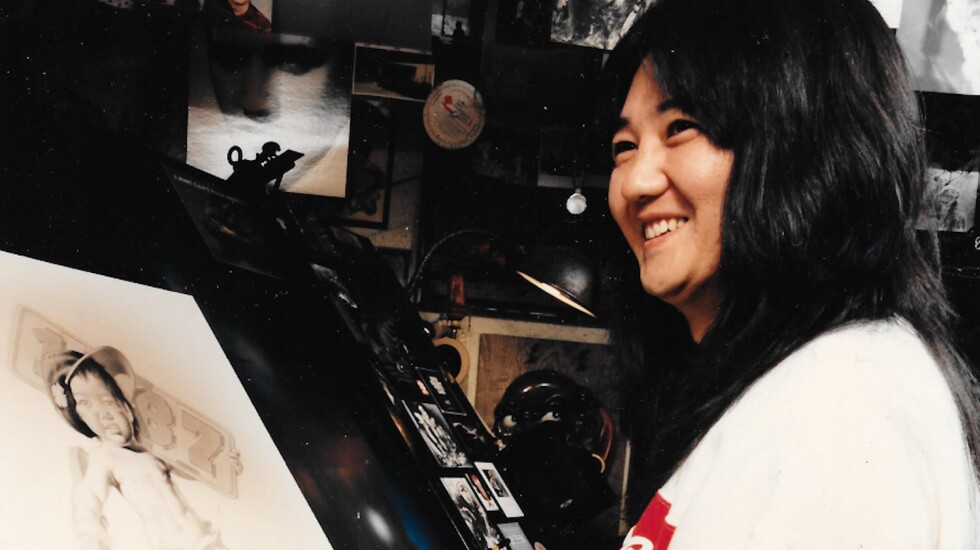

He thought the warm weather improved the flexibility of his right hand, his drawing hand, which he’d injured in his youth when a window at school slammed down on his ring and middle fingers, according to his daughter Allison Hagio-Conwell, who is also an artist.

Dawn Baillie calls his “Raging Bull” illustration a “masterpiece.”

“This is a case where the painting puts more intensity and emotion than I imagine the reference photo was able to do,” said Baillie, who has designed many movie posters, including the one for “The Silence of the Lambs” that shows star Jodie Foster with her mouth hidden by a death’s-head hawkmoth. “Dots of highlights, veins, bruising. The design of the sweat, the staredown, the hair — everything comes together to give you a taste of what the experience of this film will be like. We strive for this when we make a poster for a film: to encapsulate the experience in one striking image. Kunio Hagio’s masterpiece is a classic cultural icon. You cannot remember the film without first remembering the poster.”

Christie’s described Mr. Hagio’s portrait of De Niro as “uncannily lifelike” when it was offered at auction in 2000. It sold for $35,250.

“Kunio was probably the greatest ‘face man’ that ever picked up a brush or pencil,” said Jim Costello, his friend and agent. “He did faces like no other.”

His true-to-life images of currency once drew the attention of federal agents, according to his daughter: “He made six paintings in a row that had money in it that looked so realistic, he got flagged.”

His parents were held as prisoners of the U.S. government during World War II, incarcerated for being Japanese American. His father Allan was imprisoned at Rohwer Japanese American Relocation Center in Arkansas and his mother Toyoka Miyata at the Poston Internment Camp in Arizona. Eventually, they settled in Skokie, where young Kunio grew up on Main Street.

His father owned and operated Graphic Finishing, a printing and bookbinding firm, Allison Hagio-Conwell said.

One reason he was named Kunio was for a kindness shown to his father, according to Costello. Being Japanese American in the post-war United States, “The only job his father could get was at Cuneo Press,” he said. “Kunio told me that.”

Mr. Hagio credited his mother for his ability to keep his focus for long hours at a stretch.

“She could sit for hours on end, concentrating on precision sewing, whatever the distraction, making every stitch perfect,” he said in a 1988 interview with Communication Arts magazine. “I’m sure that it is her example that still inspires me to sit for hours and hours at a drawing board.”

Young Kunio used to go dancing at the Way Out, a teen club on Dempster Street in Skokie.

Even as a student at Niles East High School, “He could draw almost like a photograph,” said Dale Wickum, a friend and fellow alum of the long-since-closed school in Skokie.

He took classes at the School of the Art Institute but left. He told Communication Arts he found the place too “cliquish. My only friends there were two nuns.”

His favorite artists included Norman Rockwell and Frank Frazetta.

Early in his career, he drew furniture ads for Sears.

He went on to do illustrations for Playboy, Penthouse and other magazines and for clients including United Airlines. He also created cards for Magic: the Gathering.

“He started illustrating fiction articles for Playboy while all the rest of us were struggling with crummy jobs or going to school or hanging around,” Wickum said.

Mr. Hagio credited Art Paul, the designer who created the famed Playboy bunny logo, for giving him work at the magazine.

“He was immensely talented,” said photojournalist Suzanne Seed, Paul’s widow.

His detailed illustration of the tattooed face of a carnival worker was “exquisite,” Seed said.

He produced art to promote “Star Wars” and “Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.” His image of “Conan the Barbarian” decorated its VHS boxes and DVDs, Costello said.

Merv Bloch said he and his ad agency, Rosebud, which specialized in movie advertising and trailers, designed and developed the “Raging Bull” poster from a photo of De Niro, then hired Mr. Hagio to bring the image to life. Bloch said the artist’s work caught his eye while he was leafing through a design magazine.

“I came across a piece of artwork, a face that I thought was outstanding,” said Bloch, who also worked on ads for movies including “Chinatown,” “Heaven Can Wait,” “Lawrence of Arabia,” “2001: A Space Odyssey” and “Saturday Night Fever.” “I thought: ‘This would be wonderful for ‘Raging Bull.’ We did not want to sell it as another ‘Rocky’ movie.”

When Mr. Hagio completed the portrait, though, the film studio producing the movie “didn’t really respond that favorably,” Bloch said. “It was very important to enlist the enthusiasm of Scorsese and De Niro.”

“Scorsese loved the art, and so basically it was his approval and De Niro’s. They basically convinced United Artists to go with that campaign — which was a very stark campaign — and, as you know, it became an iconic movie poster.

“It’s a very hard-edged piece of art,” Bloch said. “It’s black-and-blue. It’s really tough.”

Mr. Hagio loved riding his Harley, his long hair flowing behind him, and spending time with his dog Muffin. He took her in after a grocery store employee told him she needed to find a new home for the dog.

When Communication Arts magazine asked Mr. Hagio what his favorite things to do were, he said, “Playing with my family and riding my motorcycle.”

“He was just the sweetest, most giving man,” said Rich Bleiweiss of Bleiweiss Design, former executive art director of Penthouse magazine. “If you were with Kunio, he always took out his wallet and paid for the meal.”

One time, Bleiweiss said, “He bought me a motorcycle.”

Long before the time you could send art electronically, getting a crate in the mail that contained Mr. Hagio’s work “was like Christmas morning,” Bleiweiss said.

Mr. Hagio deeply missed his wife Paulette, who died 17 years ago. He had her face tattooed on his arm.

When their kids were growing up, he would ask them every day to write down one thing they had done to help around the house and one thing they’d learned.

“He let us be who we wanted to be,” his daughter said. “The only thing he wanted for us was for us to be happy.”

“My whole family,” he once said, “roots for me.”

In addition to his daughter Allison Hagio-Conwell, Mr. Hagio is survived by his children Kitty Pesetsky, Erich Hagio-Nelson, Tina Hagio-Fuller, Jenifer Hagio Woolstenhulme and three grandchildren.

A memorial for Mr. Hagio is planned for 1 p.m. July 31 at the Midwest Buddhist Temple in Chicago. His family asked anyone attending to wear masks and consult the temple’s website regarding its COVID-19 protocol.