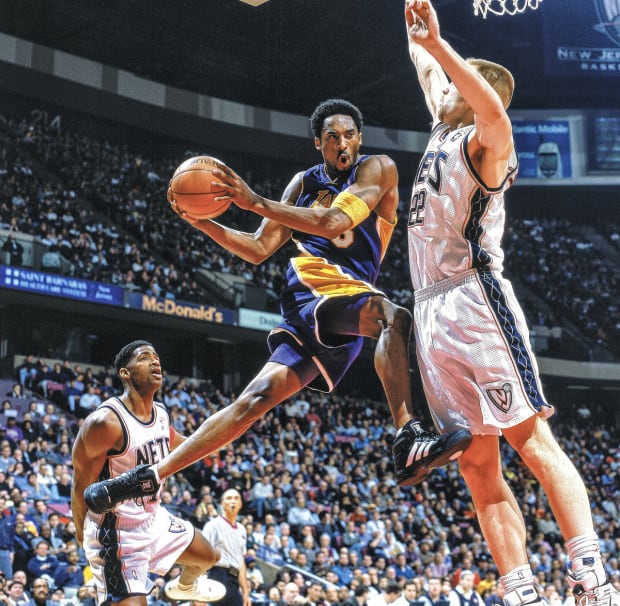

The August 2023 issue of Sports Illustrated features The Power List, the definitive index of the 50 most influential figures and forces who drive the sports world, on and off the field and court. For more on The Power List’s Icons and Leaders, like Kobe Bryant, click here.

Skylar Diggins-Smith first met him, her mentor/inspiration/idol turned most improbable friend, at a commercial shoot. They filmed in 2013, after her star turn at Notre Dame, before she became a WNBA mainstay, because Nike sponsored her and him.

Diggins-Smith had grown up in Indiana, which hit her on that afternoon, eyes widening into frisbees. We’re not in Kansas anymore, she told a friend. Eventually, she mustered the courage to approach him, this basketball deity, beloved across the NBA, the world. She asked for a photo, starstruck, and uploaded it to Instagram; her favorite picture, even now. But while her hero appeared to understand what he meant to other people, he didn’t act like he knew his presence filled hearts and weakened knees. That combination, famous and authentic, separated him. Because it was him, a star as distinct and otherworldly as any to ever play professional sports. Where fame often changes souls or vice versa, for him, those notions intersected, each improving the other, making him unrelatable and relatable, touchable and not.

Kate Frese/NBAE/Getty Images; Barry Gossage/NBAE/Getty Images

“He was Kobe and he was just Kobe, if that makes sense,” she says. “He didn’t try to be anybody else. He was real, genuine. Him.”

That Diggins-Smith refers to Kobe Bryant the same as the rest of the world, by his first name, no additional identifiers necessary, speaks to his impact, its depth. She’ll never forget that day. Nor will she forget Jan. 26, 2020, a Sunday, the worst day, when Bryant, his 13-year-old daughter Gianna, and seven others died in a helicopter crash. It took Diggins-Smith years to understand, let alone explain, the significance, to her and his family and everyone else.

She knows where she was exactly—doing interviews for USA Basketball, a passion she shared with Kobe. Knows her reaction ranged from shock to paralyzation to disbelief. Knows she frantically searched online for confirmation. Weeks became months. She couldn’t accept the truth. Favorite foods tasted terribly. If the sun came up, she saw clouds. Kobe wasn’t just a five-time NBA champion, Hall of Famer and all-time great; he was all that and way more.

Kobe spread basketball. But he also, specifically, spread women’s basketball. He called Breanna Stewart after she ruptured an Achilles tendon offering guidance on an injury he understood too well. He wore WNBA gear, proudly and publicly. He supported his daughters at the youth level. He founded the Mamba Sports Academy, a training center dedicated to access in sports. “No one had more impact,” Diggins-Smith says. Each female player saw in him the title of his book, The Mamba Mentality. Each also saw that mentality in themselves.

They weren’t alone. Kobe wrote television and commercial scripts. Kobe produced documentaries. Kobe read Harry Potter. Kobe befriended strangers, colleagues, writers, directors and celebrities. Kobe challenged himself, in basketball and outside it. Kobe invested in BodyArmor, the sports drink, then recruited other athletes (like her, Rob Gronkowski, Mike Trout, Andrew Luck) to endorse it. He pushed for an equity stake, then pushed to enlarge it, writing all the scripts and convincing proud athletes with egos and management teams to film uncomfortable spots. (Diggins-Smith led a Jazzercise class, in full neon! James Harden dressed as a pirate!) His initial $6 million brand investment grew into a valuation of around $400 million, or more than he made in his NBA career ($323 million).“That was the Mamba mentality, his mentality,” he says. “To find and nurture the best version of yourself.”

She sees his death as a propulsion of sorts, an accelerant for followers of his famous mentality and its ongoing, ever-widening spread. No one will ever be like Kobe. But Emmy, Grammy and Oscar winners can all borrow from his approach, as can athletes, in all sports, actors, Harry Potter aficionados, Guitar Hero video game designers, Italian basketball coaches, auctioneers, graffiti artists, even Beyoncé’s dad. The tired cliché of many things to many people was Kobe and limited Kobe, who he was and what he meant. He was all things, to all sorts of people, and Diggins-Smith believes that stems from the rare duality baked into him.

“Kobe is everywhere,” she says. For his life, his death and everything in between. Forever. Maybe, because it’s Kobe, far beyond forever, even.

In 1999, Destiny’s Child hit No. 1 on the Billboard Top 100 for the first time with “Bills, Bills, Bills.” The same year, Bryant began his fourth NBA season, which would culminate in his first title. The group and the athlete shared everything from burgeoning celebrity to mutual appreciation, along with a smidge of fate that brought them all together.

Mathew Knowles was Destiny’s manager. He knew all about Kobe, even that the phenom had a crush on one group member. (Knowles declines to say who, citing his book on PR strategy, noting one particular tip: You Don’t Have to Answer Every Question.) Back then, Destiny’s Child booked Kobe to guest star in a music video.

“Bug a Boo” peaked at No. 33 on the Top 100. It’s filmed on the street, with group members waving off advances from dudes in a nearby convertible, before dashing inside a door marked “MEN’S LOCKER ROOM,” passing lockers and athletes, before a young Beyoncé spies a young Kobe lacing up his sneakers. Bryant’s spot lasts for only a handful of seconds, but it wasn’t his cameo that stood out.

There’s another clip from the shoot available on YouTube. It lasts for 23 seconds and features famous people when they’re young. The camera pans across the group, starting with Knowles’s daughter, Beyoncé, who yells out, “I’m ready, Daddy! Come on! Come on, Daddy!”

The camera pans away, revealing a basketball court. Bryant is dressed in all white—tank top, shorts, socks and sneakers. He dribbles a ball, as Knowles walks toward him in long, black pants and a red shirt. He’s dressed for work, and this counts, because he played basketball in college, winning two titles at Fisk University, a private, historically Black college in Nashville.

Kobe fakes, jab steps with his right leg and fires, the exact move he perpetually deployed for 20 seasons. His attempt clangs off the front rim, before ricocheting off the backboard. Next, Kobe lazily assumes a defensive stance. Knowles wiggles left, speeds by and scores. The crowd on set goes wild. Kobe would later tell TMZ Sports he didn’t think Mr. Knowles “made a basket after that.” Incorrect, Knowles says. He made one more, a jumper. After that, he admits, it was a wrap.

Knowles saw the man Kobe would become, was becoming. His ethos—that mentality he’d turn into a book title—stood out, even then. Kobe came across as smart and versatile and driven. And not just driven to do one thing exceptionally well but several, 6-6-6 applied all over, all at once. His book wouldn’t be published for nearly two decades. But he already spent each offseason workout completing two hours of running, two of hoops and two of weightlifting. He did all three for six hours a day, six days a week, six offseason months a year. No exceptions. This resonated with Knowles, who thought, “That’s the work required for greatness.”

Kobe confirmed as much as his interests stretched and impact soared. Knowles saw Kobe as an elite father and one of the best players to ever pick up a basketball. He loved Kobe’s documentary work. He witnessed Kobe’s process obsession up close, when Kobe asked for tickets to a Beyoncé concert but showed up as both a fan and someone who considered her an athlete. Nobody had ever called Beyoncé that before, her father says. Kobe saw what others missed. How did she maintain that pace for three hours with one short break? And move like that, with grace, power, purpose?

Knowles sensed the influence Kobe would eventually hold, and in so many places that had nothing to do with sports. He can only think of one thing Kobe did not do well. Evidence is another Destiny’s Child song, the “Say My Name” remix. Kobe rapped on that song, proving that Shaq wasn’t the only musically challenged member of their Lakers dynasty. His verse, the third, comes in over the chorus. His voice is soft, slow at first, but rises in tempo and volume. The tenor falls between spurned lover and tsk-tsking narcissist.

Kobe influenced every space he entered, touched or immersed in. Except that one. “If I were his manager, I’d tell him to stick to basketball,” the music mogul says.

Before the 2018 college football season at Alabama, Kobe popped by campus for a visit. This was August, only months removed from The Benching—when Nick Saban swapped Jalen Hurts for Tua Tagovailoa at halftime of the national championship game. Tagovailoa would remain the starter. But Kobe’s message was intended to resonate with both, with all.

Hurts sat up front as Bryant told the Crimson Tide to edit your life. Everyone always asked for his secrets, for the edge he gleaned and how he gleaned it. There really wasn’t a secret at all. Just editing. “I learned at an early age, I have to edit my life,” he said. “If there’s s--- that’s bad for me, if there are people that are bad for me, I have to edit them out of my life.”

The message resonated, especially with Hurts, who’s built similarly, every action and word precise. Hurts had crafted a plan for the rest of his career—serve as an elite backup if he never regained the starting role; make the most of any spot duty, or spell Tagovailoa due to injury; graduate, in part to open up transfer options; NFL; domination.

Kobe’s message marked one more motivational push. Hurts stuck to his plan. He played some but not much, supported and concentrated on what he could directly impact. When Tua hurt both ankles in the SEC championship game against Georgia, Hurts came in and sparked a comeback despite an injury of his own. Same field as the benching. Same opponent. An edited life … won.

Hurts transferred to Oklahoma, made the NFL, forced the Eagles to reconsider their plans at quarterback, continued to improve, continued editing and, amid an MVP campaign last season, pushed Philadelphia back into the Super Bowl. His sports performance director in Philly, Ted Rath, had visited Alabama’s campus before the draft in 2020. He learned about the speech then and huddled with Hurts as Super Bowl LVII approached. Both decided they would use it.

The Eagles flew to Arizona, where on Day 1 of Super Bowl week, Rath stood before the team inside a weight room. He hit play on his laptop, and Kobe’s speech from Bama boomed across the room.

Hadn’t that been the point of their last month together? Rath asked Hurts later. Not listening to agents, relatives nor friends on when he should return. Missing two games he desperately wanted to play. Looking deeply inward. Focusing on recovery, nothing else. Editing his story and, by extension, the Eagles’ season.

“I see a lot of Kobe in Jalen,” Rath says. The quarterback led his fired-up team out of the weight room on that afternoon in Arizona, everyone floating onto the practice field. The Eagles conducted their best practice of the season.

As if intent on proving Rath correct, Hurts made Kobe the subject of his offseason study last spring. He watched how Kobe’s leadership evolved, how much he said when he didn’t say anything, how his words, when used sparingly and combined with his daily example, lifted teams beyond where they should have gone.

Hurts is still editing. Rath looks at his mentality and sees Kobe. How many other trainers could look at their superstar and say exactly the same thing?

What’s in a name? A lot, Coby Bryant learned—from Day 1. For him, the answer was more than most, more than anyone he knew. Try playing basketball, even in youth leagues, when your name is Coby Bryant, and you never met a shot you didn’t hoist. Try watching clips of the NBA superstar you’re named after when you’re 7, to understand the standard you must meet. Try buying school lunch and having the clerk ask for your ID, because they don’t believe that name is your name.

Kyle Terada/USA TODAY Sports

This started with a baby born in Ohio and into a family of NBA fans. His father, Ronnie Bryant, made a family in Cleveland. But it wasn’t LeBron James who most inspired him. Kobe did. In naming his youngest son, Ronnie paid homage to his favorite player. (A mild family dispute lingers: Coby says his older brother, Christian, claims he came up with the name. At age 7! “Older brothers always want to take credit,” Coby says, laughing.) Regardless, the family changed the spelling intentionally, so that Coby could shape a distinct legacy in Kobe’s image. In a world now filled with so many Kobes, Cobis and Cobys, hundreds, even thousands, of other families, took the same approach.

The significance seeped into this young Coby’s soul. He embraced the Mamba Mentality and took that approach into football and toiled toward stardom (at powerhouse Glenville, at the University of Cincinnati and in Seattle, with the Seahawks). As a college senior, he won the Jim Thorpe Award, as the nation’s top defensive back. Before Cincinnati competed in the kind of game it never reached—a College Football Playoff semifinal against Alabama—Coby switched his jersey number from 7 to 8. More homage.

When Seattle selected him in the 2022 draft’s fourth round, the Seahawks didn’t wait to draw the obvious connection. They asked whether he would wear No. 8 in the NFL. Coby didn’t hesitate, while slotting into a defense (and team) that far exceeded reasonable expectations. His four forced fumbles tied for third in the NFL.

“It’s no pressure,” Coby says. “It’s a privilege. That’s the best way to represent.”

Coby says Kobe came up all the time, like whenever someone pointed out those expectations and how they might overcome them. The Seahawks’ surprise season hinged on that mentality. How many teams, in how many sports, at how many age levels, could say the same?

After the Super Bowl 50 triumph for Von Miller and the Broncos, the high life morphed into struggle city. Denver never found another quarterback and sunk back toward the bottom of the AFC West, while Miller endured two serious injuries. His mental performance coach, Trevor Moawad, died suddenly from cancer. The Broncos moved on.

Miller moved to Los Angeles, carrying Kobe with him, in the literal sense, inking a Kobe-Lakers tattoo on the same left leg he injured. He also created a file on one of his 393 iPhones to store inspirational clips. Kobe was in more than half of them.

As Miller showed off the tat and the folder before Super Bowl LVI, he said, “That’s the Mamba Mentality. Trying to be the best version of yourself.”

Miller paused, then plunged, mind drifting to the worst stretch, the beginning of 2020. Kobe was dead. Miller was hurt, sitting around. His stock had never been lower; his 8 sacks in ’19 marked the second-lowest tally of his career. Doubt crept in, as he wondered whether he would ever become the force who willed Denver to a championship. Miller set up in his Denver basement, searched for anything he could find on Kobe—docs, clips, interviews—and hit play.

After leaving Denver, Miller rented a house near the Rams facility in Thousand Oaks. He soon realized that Kobe’s helicopter crashed right down the street. Every day, he saw strangers park and walk toward the spot where Kobe died. All types of people. From all types of lives. Some of his neighbors sat in their yards and just stared toward the crash site. Driving past, Miller said it “is really like a movie, all these things and people connecting from the mentality he set.”

Kobe carved a legacy. Miller wanted the same. He won another Super Bowl with the Rams, left for Buffalo, and set the Bills on a championship track. Another injury ended his 2022 season. Another rehab loomed, at age 34.

Miller already knew where to look for inspiration. Same person. Same place. Same expectation, even, for the upcoming NFL season. A Super Bowl that owes, in part, to Kobe, who Miller says taught him to never relax, continue striving and—the twist—stay likable. “Sometimes, you just gotta be a good dude,” Miller says. “Sometimes, in life, relationships go further than performance. I got that from Kobe.”

Why not both, though, for the rare human capable of such things? Kobe’s death, Miller adds, “forced me to create this monster, to take full advantage of the opportunity that I got.” He got that from Kobe, too.

Pau Gasol played with Kobe for nearly seven seasons and spent two decades in the NBA. Point blank, Gasol says, he never had a more competitive teammate. No one else comes close. Kobe imprinted that mentality on every player he ever played with. But few felt his impact as deeply as Gasol, who admired Kobe’s edge and killer instinct.

They bonded, in part, due to what they shared: long and decorated NBA careers; both stars; both close to the end, with growing families and young children and aims beyond basketball. Gasol says he had reached the point in middle age where he understood he needed to grow in maturity and readiness for life after hoops. Nobody had done that like Kobe, either.

Jayne Kamin-Oncea/USA TODAY Sports

Kobe pushed him, because Kobe pushed everyone. But Kobe pushed no one harder than himself, and his example, more than anything he said, more than anything he shared, pushed those in his orbit the hardest. His daily routine, Gasol says, spoke for him. “Hey, if you want to be the best at something, this is how you do it.”

Gasol admired Kobe, and the decision to care for the family Kobe left behind wasn’t much of a decision at all. Gasol had watched Kobe become perhaps the world’s most famous #girldad, loving and involved. Family members came with Kobe to the Olympics, so he could multitask, implementing his mentality in two places at once. He saw Kobe at dinners around his children, his doting nature. “There was a lot more to him than [most] could see,” Gasol says.

So he keeps up the relationships. He checks in on the kids, offers to help Vanessa with anything and assists with continuing Kobe’s incomplete vision. Kobe had one, of course. Had several. But the natural evolution, how he would have adapted for himself and his family, was cut short. Gasol must replace what never can be, to bring some of Kobe to Kobe’s family, because Kobe himself cannot.

Gasol learned of Kobe’s death while driving home from a basketball game. Maybe Kobe would have liked that. Who knows? Gasol doesn’t fully agree with those who think Kobe’s influence elevated in death. It has, of course, he says. But it would have anyway, maybe even higher, as Kobe pushed his family upward, dived into more obsessions, changed more lives.

How much? How many? Gasol will never know. For now, he says, “I miss him, his presence, his influence, spending time together, on a daily basis.”

Is that enough? It has to be. For now and forever. They’re all trying to do the same thing, to bring Kobe with them, to influence as he influenced. If only Kobe hadn’t lifted the bar so high. At least he taught them, like Gasol, preparing them unknowingly for the immense task of being him, as much as anyone can be Kobe.

“That’s what I carry with me,” Gasol says.

They all carry him. Diggins-Smith knew the perfect way to honor Kobe. Hence the jersey—No. 33 from Lower Merion High—she wore to a game last July. She found the replica online, while searching with a friend, and purchased it immediately. But she also knew, “You gotta be careful,” when wearing one of Kobe’s jerseys to the office, especially when that office is a basketball court. Not to worry. Playing for the Phoenix Mercury, she dropped 35 points, six rebounds and six assists.

“You put that jersey on, and you feel like you’re in Space Jam,” she says. “Everything comes to life. It’s like, O.K., I got that power. Whoever got me, got problems.”

Even on that day, memorable as it was, Diggins-Smith understood something else, something even more powerful. Simply honoring Kobe on the basketball court wasn’t nearly enough. Kobe’s influence made her a better mother. A better teammate. A more empathetic person. A more well-rounded one.

Months passed. Then years. She watched his Hall of Fame induction in May 2021, her screen yet more proof of how many Kobe impacted and how deeply. There were young women in the crowd. Old men. Vanessa. Basketball luminaries. Hollywood big shots. She wished only that the one person who tethered so many unconnected people, could have spoken.

“He was bigger in person,” she says. “Tall, big personality, that presence.”

He might be bigger now, in death, the sad but powerful fate of worldwide icons. Gone too soon. But still filling the sports world, the world, with deep purpose. Still Kobe. Still influencing.

The call that Diggins-Smith made in June, to discuss Kobe’s lasting and spreading impact, is proof. It took place shortly after the start of the WNBA season, but she wasn’t with the Mercury. She was at home, having given birth to her second child (her first, a boy named Seven, was born in 2019).

Because of Kobe, in part, she produced a documentary series for Nickelodeon. Because of Kobe, she continued to refine her professional basketball career. Because of Kobe, she pursued more Olympic glory. And because of Kobe, her decision to step away from part of a WNBA season, her 10th, closer to the end than the beginning, was easy.

She had a baby girl, although she hasn’t released the name publicly yet. That girl may play basketball. Kobe taught Diggins-Smith many things, but if he only taught her one thing, it was this: to embrace life, all of it, in search of balance and greatness and passions. “He forced everyone to look deeply inward,” she says. “To ask: how can we do our part?”

This is how. By loving basketball and family. And by supporting that baby girl, in whatever she decides to do, as long as a certain mentality is the benchmark, the standard, the soul.