Depression is a leading cause of disability worldwide, but an erstwhile party drug is projected to flip the narrative and improve the lives of those in desperate need. Over the last several years, ketamine has emerged as a vanquisher of depression — especially forms impervious to conventional treatment, known as treatment-resistant depression — by rewiring the brain, encouraging a phenomenon known as neuroplasticity.

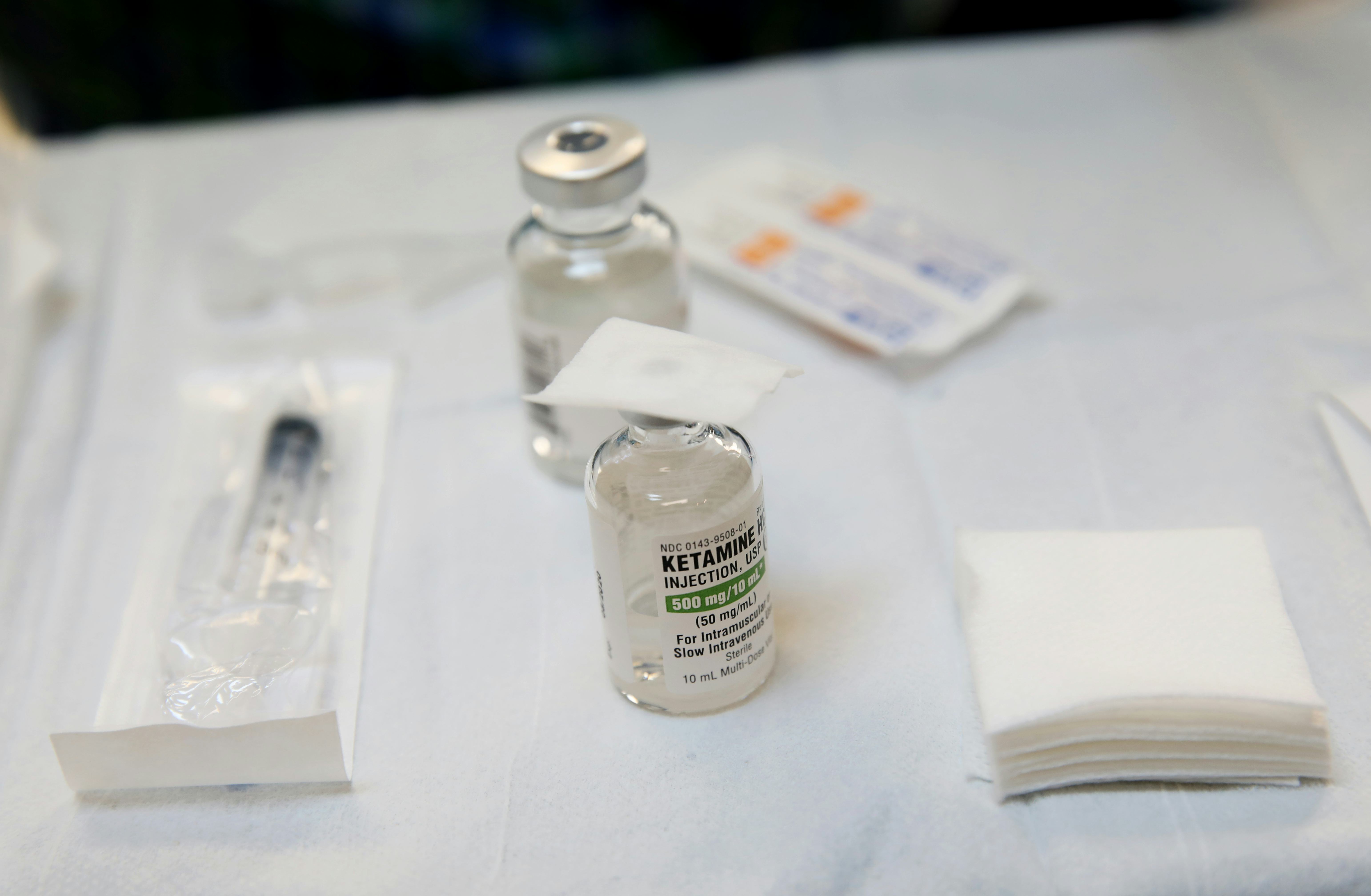

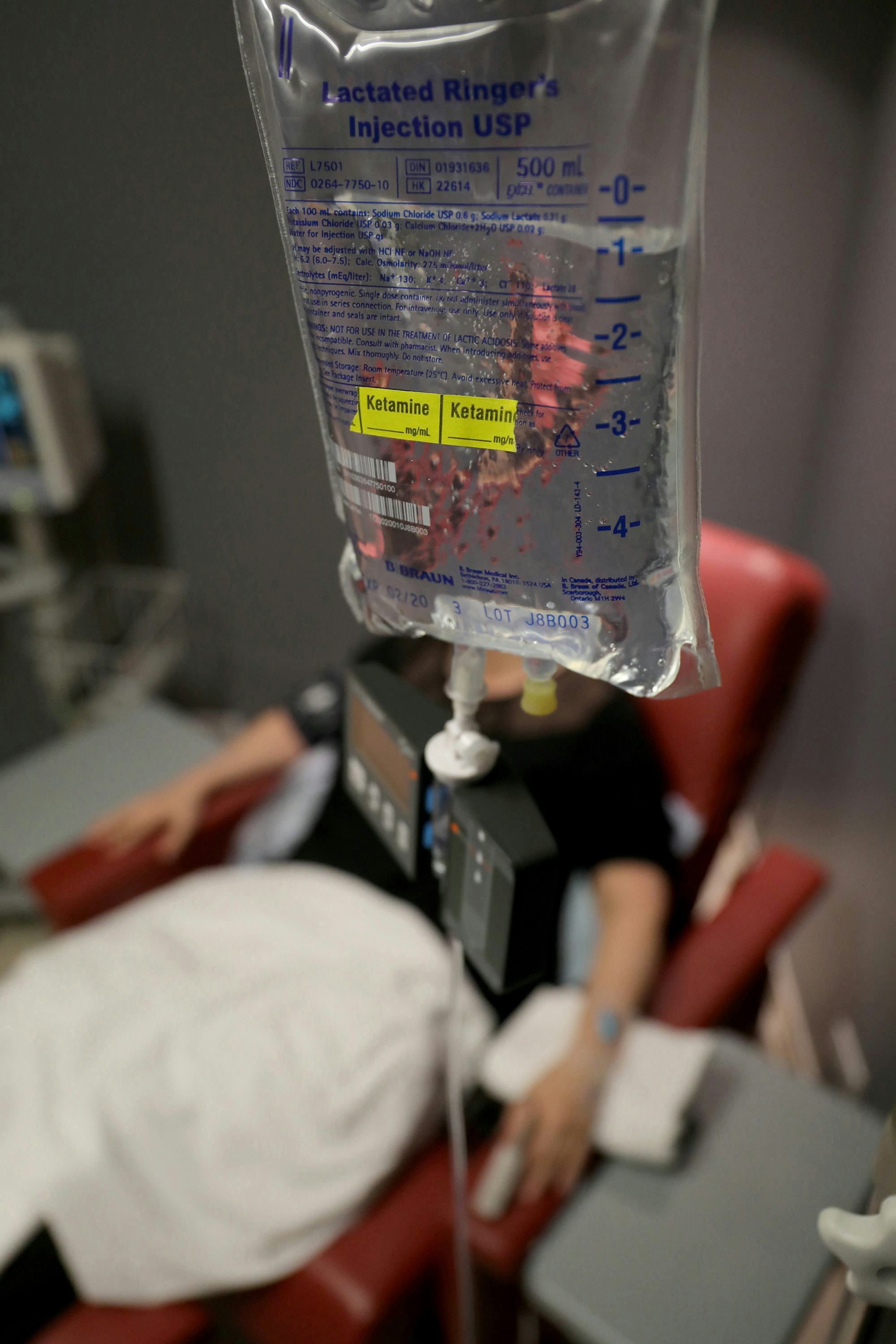

Currently, ketamine is only approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as an anesthetic; it isn’t approved to treat any mental health conditions. But it’s seeing off-label use in clinics offering intravenous infusions (often at a hefty price), through teletherapy, and more recently, through nasal sprays. In 2019, the FDA approved Spravato, an intranasal nasal spray containing esketamine, a molecule derived from the drug, based on clinical trials demonstrating its potency in not only treating but keeping treatment-resistant depression at bay.

Now, a new study is offering more evidence in support of esketamine, positioning the nasal spray as even more effective than antidepressant medications like quetiapine, also known as Seroquel. In a clinical trial spanning 24 countries, among 336 participants already on an antidepressant, 28 percent saw remission of their symptoms after eight weeks on the esketamine nasal spray versus 18 percent of a similar-sized group taking quetiapine in addition to their usual antidepressants. After about 32 weeks, 22 percent of the esketamine remained in remission as opposed to 14 percent in the quetiapine group.

Medical experts say these results are promising for patients with treatment-resistant depression, but more research is needed to see how truly effective the esketamine nasal spray is compared to other antidepressants — not just quetiapine — and whether the former party drug is safe for patients to take long-term.

The findings were published Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Lasting remission

While a majority of individuals with depression will get better with conventional antidepressant medications, 10 to 30 percent don’t respond to treatment at all. According to a large-scale clinical trial called the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (or STAR*D) study, those getting treatment for depression will generally enter remission (or return to normal levels of functioning) in a step-wise fashion: 30 percent after the first treatment, 50 percent after two treatments, 60 percent after three, and 70 percent after four.

Studies show esketamine does seem to work pretty well when compared against a placebo for individuals with hard-to-treat depression, Allan Young, director of the Center for Affective Disorders at King’s College London, who co-led the study, tells Inverse. However, there hasn’t been much data on how the esketamine nasal spray stacks up against other recognized, more affordable treatment options like quetiapine.

To suss out how well it works against other treatments, 676 adults between 18 and 74 were recruited and screened from August 2020 to November 2021 across 24 countries. These were individuals with treatment-resistant depression already on an antidepressant — either a selective serotonin or serotonin-norepinephrine inhibitor. Participants were randomly put into two groups, but knew what they were getting: the esketamine sprayed up the nose twice a week in a health care setting or quetiapine taken daily.

“A very important thing of this study was to look at not only the people who got better but also stayed better over the course of 32 weeks,” says Young.

And that’s what the researchers saw. After eight weeks of treatment, 28 percent of the esketamine group saw remission of their treatment-resistant depression, and 24 weeks after the initial treatment, 22 percent didn’t relapse. (Whether someone was functioning back to normal was determined by the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, a 10-item clinician-rated scale used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms in those with mood disorders.) This is compared to 18 percent in the quetiapine group, 14 percent of whom didn’t relapse after the same time period.

Therapeutic potential with many questions

Maurizio Fava, chief of psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, who wasn’t involved in the study, told Inverse in an email that the findings were in line with what many clinicians have come to expect with the efficacy of nasal esketamine for people with treatment-resistant depression. However, because the study was limited to comparing esketamine to quetiapine, it’s hard to say how much better the nasal spray is compared to other drugs used for treatment-resistant depression.

For Amit Anand, professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, who was also not involved in the study, there are concerns about how much the placebo effect may be at play during the course of the entire clinical trial, given participants knew what they were getting and the fact esketamine can only be administered in-person by a health care professional.

“There’s a big placebo effect of giving that much attention to a patient,” he tells Inverse. He also mentions other factors at play, separate from the placebo effect. “People get a little bit of high when they get [the esketamine nasal spray].”

While giving short-term doses of esketamine appears to be safe for patients, Anand says there’s the issue of potential addiction associated with esketamine with prolonged use, which needs to be further investigated. Right now, it’s not entirely clear how long esketamine can keep depressive symptoms at bay. Young says when treating severe or recurrent depression with conventional antidepressants, a patient would need to remain on medication for about six months although this can be as long as two years. He believes this could be the same for nasal esketamine.

Like ketamine infusions, esketamine nasal sprays aren’t cheap, but they may be more cost-effective, according to some studies. As millions of people around the world suffer from depression, the hope remains for esketamine to revolutionize the way we approach mental health care.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this story incorrectly referred to the nasal spray used in the clinical trial as ketamine nasal spray when, in fact, it is esketamine nasal spray. Esketamine is a derivative of the ketamine molecule. Additionally, a previous version of this story had an incorrect spelling of Spravato, a brand name of the esketamine nasal spray. We are glad to correct the errors.