It was all going great until it wasn’t.

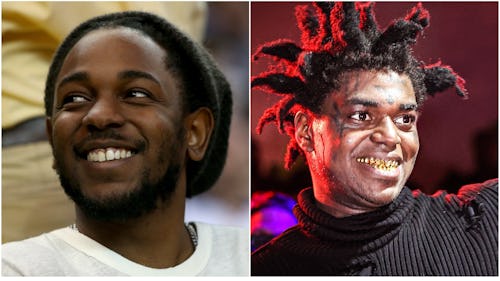

Friday’s drop of Kendrick Lamar’s long-awaited Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers was supposed to be the grand finale of a month of big hip-hop album releases. It’s safe to say that every other rap release was set up strategically (Billboard chart-topping wise) to come before K. Dot’s to avoid competing with the superstar.

With five years since his Pulitzer-winning DAMN, I was curious to see who would be featured on this album. Many on Twitter hoped for guest appearances by Andre 3000 and J. Cole, with some even predicting more underground talent. When the album finally dropped, there was a well-received feature by his signee Baby Keem, along with cameos by Sampha, Summer Walker, and even Beth Gibbons, of the band Portishead. But the one guest act that continues to be talked about is one that really didn’t contribute anything notable at all.

Meet Kodak Black, again.

When I saw the controversial rapper featured on Lamar’s album, my eyes instantly rolled. Like what are we doing right now? Future had already featured Kodak two weeks ago on his latest release – but were we expecting anything less toxic from a man who still works with Kanye? For Kendrick to be doing the same thing felt like a misguided betrayal on a project that feels like his most self-reflective endeavor yet.

For those who don’t already know, Kodak Black (legally named Bill Kapri) is a problem.

The 24-year-old rapper has a penchant for getting into legal problems, but more notoriously being involved in incidents pertaining to the abuse of women. Last year, he took a plea deal that involved him pleading guilty to a lesser charge of first-degree assault and battery after being charged for sexually assaulting a high school girl following a concert in 2016. In April 2017, he was accused of punching and kicking a woman at a Miami-Dade strip club. Although no formal charges were made, the situation did result in him violating his probation.

When not being in legal hot water, Kodak is constantly perpetuating misogyny elsewhere. In 2017, he shared a live Instagram filming of his friends receiving oral sex from a young naked woman for the world to see. He’s constantly made it a point to make colorist remarks about dark-skinned women, once saying: “I love African American women, but I just don’t like my skin complexion. We too gutter, light-skinned women more sensitive. … Light-skinned women, we can break them down easy.” And for all of Kendrick’s admiration for slain rapper Nipsey Hustle, it’s hard for him not to have forgotten the blowback Kodak received for once saying that “I’ll give her a whole year” referring to Nipsey’s grieving fiance Lauren London, before he’d try to sleep with her. “She might need a whole year to be crying and shit for [Nipsey].”

So why would Kendrick put this man on the most highly-anticipated album of the year?

Because like many before him, K. Dot thinks he’s a redeemer saying something more than just perpetuating the same cycle of apologists before him.

For starters, Kodak isn’t doing anything remarkably different and special on the album’s track “Silent Hill” or with his interlude appearance on “Rich” – but that’s beside the point. If music is more than just the art of sound and lyrics, then the politics of its curators should also be discussed. For all of the consciousness that Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers attempts to convey around the topics of sexual abuse and trauma, it undermines it by giving a platform to a known abuser. Kendrick talks about breaking the “generational trauma” of his family on the powerful “Mother I Sober,” but seems to not recognize such pain in the culture of the genre he’s often rapping about elsewhere throughout the album.

We can’t act like we haven’t seen this from K. Dot before.

In 2018, Kendrick reportedly used his star power to try to influence Spotify to reverse their decision on banning slain rapper XXXTentacion for a history of violence towards women. Lamar’s camp reportedly went as far as threatening to pull his own music off the streaming app in protest if they kept the ban up. To see him four years later still caping for problematic men in music is an unshakable letdown.

But again, none of this is new, forward, or progressive. Artists like Kendrick, Kanye West, Future, and others who think they are making a revolutionary statement by still embracing their harmful peers (such as Kodak, Tory Lanez, DaBaby, Marilyn Manson, and the ilk) in this way are doing quite the opposite. To them, it’s probably a shock-jock, oh-no-he-didn’t moment meant to push back on how the public seeks to cancel, condemn, and shame people. It could also be because hip-hop has often been the genre that embraced people who have been accused (and been convicted of) crimes – allowing them to pride themselves in not being as judgmental as others. But in reality, it’s actually doubling down on divorcing these toxic individuals from accountability and reinforcing the all-too-familiar trend of victim-blaming.

What’s much harder for cishet men in hip-hop is to actually distance themselves from the chains of misogynoir, anti-queerness, and all of the hate we hope “conscious” rappers shun. Instead, they continue to relish in this ambiguity of saying contraction positioned as creative nuance. Kendrick’s latest album is filled with them. One that embraces queer and transgender family members, while dropping f-slurs and deadnaming them. One that speaks on therapy and healing, while giving unchecked abusers the mic. One that continues to center him as hip-hop’s current leader, while excluding features from female rappers, or the LGBTQIA voices he acts as though he’s more aware of.

At 30 years old, I’ve come to accept that maybe the rapper that I once embraced while in college isn’t as self-aware as I would have hoped he would be by now – and perhaps it’s time for us to consider growing up and moving on.