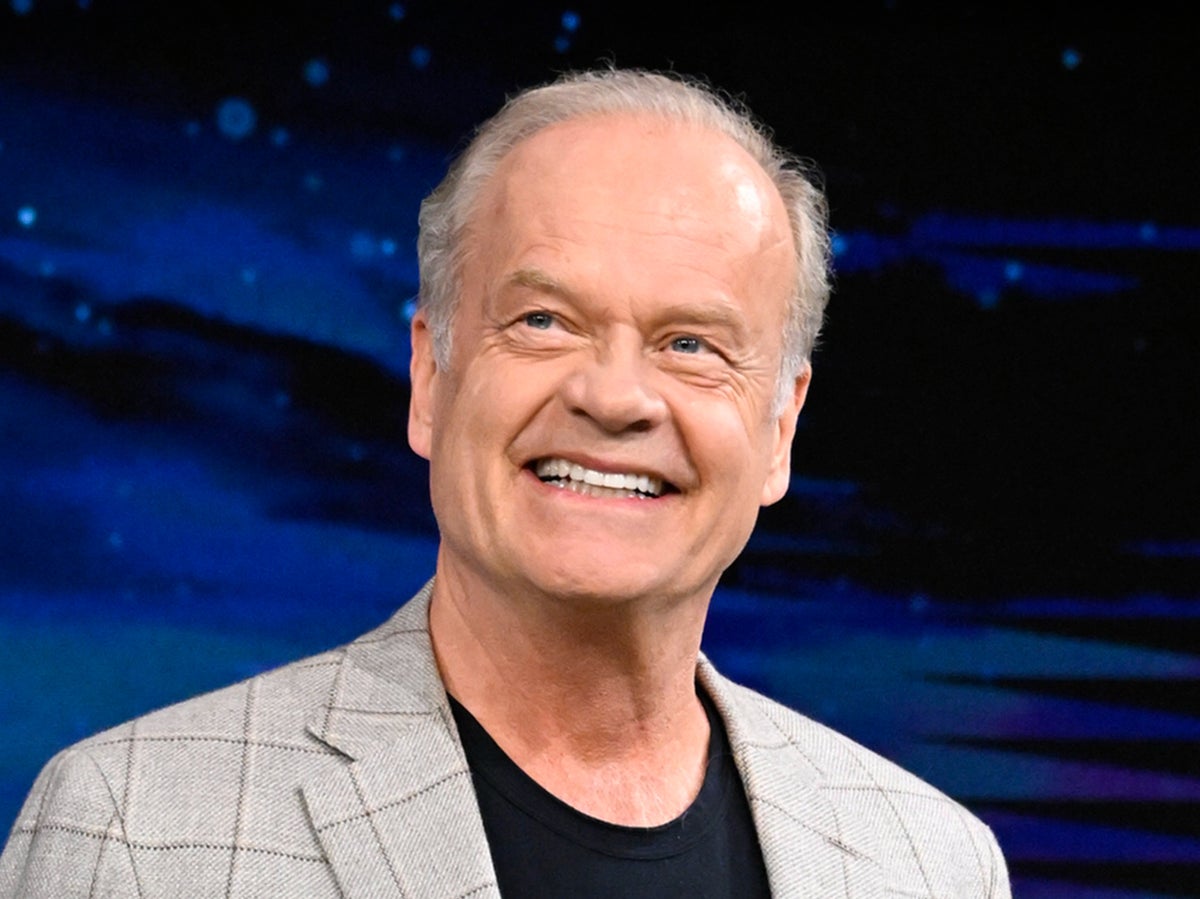

It’s not such a horrible thing, a life of faith,” says Kelsey Grammer, with the soft, faintly amused cadence of a parent reading a picture book to a child. The 68-year-old actor, best known for his multi-Emmy-winning two-decade stint as psychiatrist Frasier Crane in Cheers (1984-1993) and its spin-off Frasier (1993-2004), can certainly testify to that. He’s bringing the good doctor back to life later this year, of course, in a hotly (and anxiously) anticipated revival series. But today he is mostly here to talk to me about faith – about being “reborn” as a devout Christian, and his new religious biopic, Jesus Revolution.

Grammer speaks to me over video from a sparsely decorated room “in the bowels of ITV” (he’s appearing on This Morning shortly after our interview). From the moment he starts talking, I find it almost impossible not to hear the voice of Frasier Crane emanating from Grammer’s formidably square jaw – the mix of honeyed warmth and baritonal gravitas that rendered him so thoroughly convincing as a lovelorn headshrinker.

Like Frasier, Grammer makes for eloquent and erudite company, quoting Shakespeare and the New Testament. It may be just this intellectual ease that Cheers producers were able to sense during his first guest appearance, as the assertive boyfriend of Shelley Long’s bar waitress Diane Chambers. His role – initially meant to last a few episodes – ended up becoming the part of a lifetime, and established Grammer as one of the finest comic actors in the history of television.

But for now, let’s stick to Jesus Revolution. In the film, Grammer plays Chuck Smith, a real-life pastor who founded the Calvary Chapel church in Orange County, California, in the 1960s. Chuck starts the film as a fusty non-denominational minister (“the very definition of a square”, his daughter, played by Ally Ioannides, says), before the arrival of hippie evangelist Lonnie Frisbee (Jonathan Roumie) opens him up to a new congregation of disaffected youths.

Joel Courtney plays evangelist Greg Laurie, the film’s protagonist. Jesus Revolution has impressively slick production for a Christian movie; the project is clearly one that is close to Grammer’s heart. Or perhaps his soul. “We’ve done a lot of different Jesus movies, haven’t we?” he muses. “There was The Greatest Story Ever Told. Passion of the Christ. The Scorsese one as well [The Last Temptation of Christ]. But it’s a story that remains relevant, because this Jesus character does seem to have an eternal ability to heal people.”

Grammer was raised as a Christian Scientist. What’s special about Jesus Revolution, Grammer argues, is that it takes a recognisable 20th-century moment as a “historical reference point – an inflection point, if you will”, and uses it to explore how perceptions of Jesus were changed in a contemporary society. “People are scared to talk about their faith,” he adds. “I hope that maybe people will talk a little bit more about faith as a result of this film.”

During production, Grammer visited California’s Corona del Mar beach, where Smith carried out mass baptisms; he was approached by several people who said that they had been baptised by Smith, or married by him. “It was wonderful to see that evidence of what a life of faith can be in a person,” he says. “And being in California and hearing people say that... you know, you don’t hear it too much in California.” There’s a hint of loaded meaning to this last remark.

As one might expect from a film made with an explicitly religious agenda, Jesus Revolution presents a somewhat tilted version of history. The real Pastor Smith was criticised throughout his lifetime for his church’s stance on LGBT+ people; he once described homosexuality as “the final affront against God”. Smith’s eventual split from Frisbee has often been attributed to conflicts over Frisbee’s own homosexuality. Watching Jesus Revolution, you wouldn’t know this. Grammer seems sceptical of this version of events, claiming that he is “not sure [Frisbee] left the church because he was gay... It may be that that has become part of the story because people want it to be,” he avers.

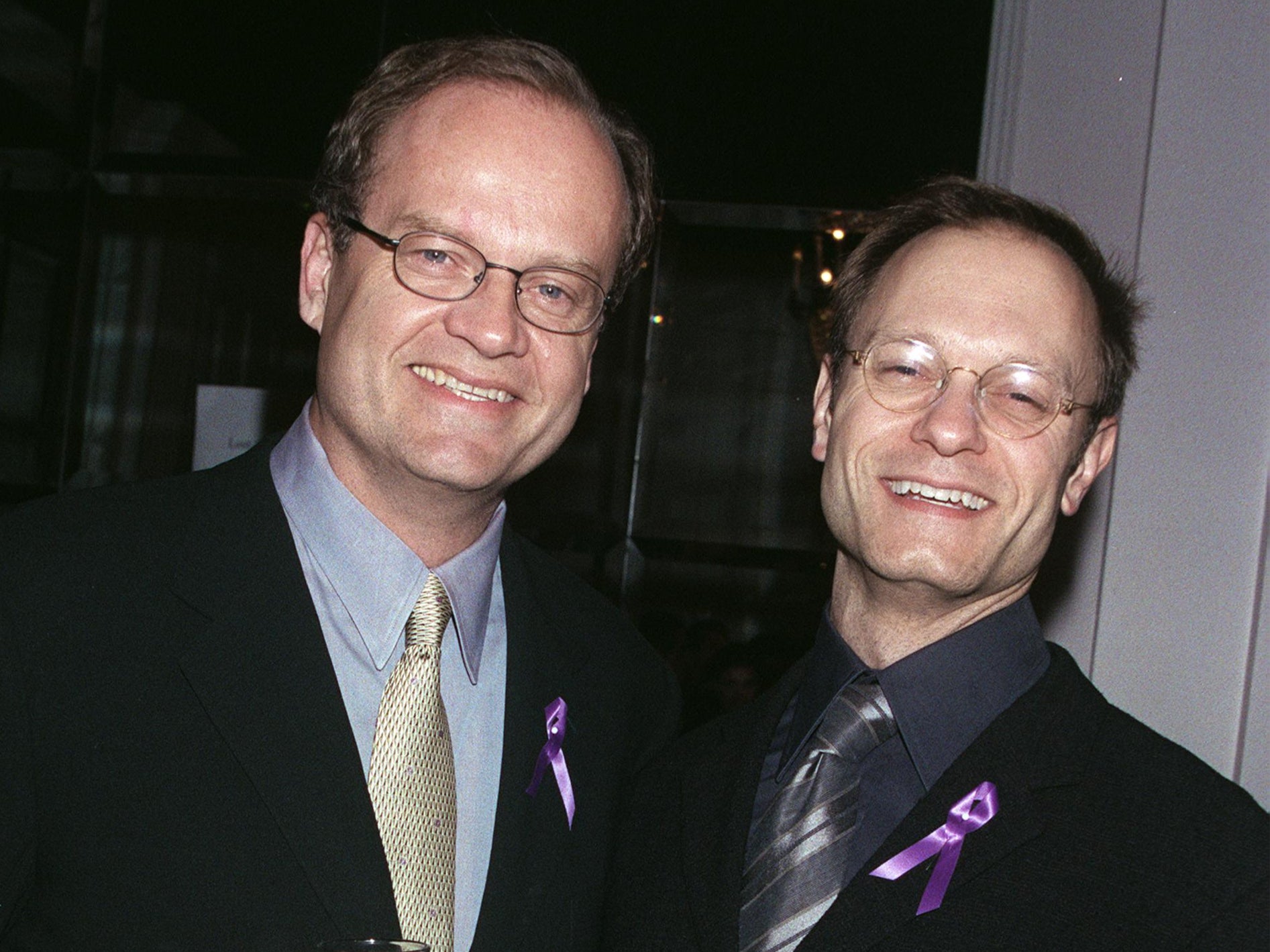

It’s worth noting, at this point, just how significant Frasier was as a piece of gay television. Besides the involvement of several gay writers, gay stars (including David Hyde Pierce, who played Frasier’s uptight brother Niles, and Dan Butler, who played Frasier’s womanising colleague “Bulldog”), and overtly gay-themed storylines, the very premise of Frasier – an effete heterosexual man’s discordant relationship with his more conventionally masculine father – spoke keenly to the experience of many queer viewers. So how does Grammer reconcile this side of the church with his own views on sexuality?

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7-days

New subscribers only. £6.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7-days

New subscribers only. £6.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

He nods. “I think Christianity is a welcoming ethic. You come from a place of love no matter what. And I think that’s who Chuck was. And of course, Lonnie returned to the church and preached again beside Chuck. Chuck eulogised him when he died. So I think he probably leaves a living testimony that those presumptions about that time in history, in his church, may be a bit exaggerated.”

It’s true that there is some ambiguity over the exact nature of Smith and Frisbee’s falling out; ideological conflicts were also said to have played a part. But Smith’s own views on LGBT+ people were well documented. Today, Calvary Chapel – which boasts more than 1,000 locations across the US alone – has continued to attract criticism for platforming anti-LGBT+ views.

Grammer was 13 years old when the events of Jesus Revolution took place. For him, the Sixties counterculture was something he experienced from the periphery. “Where was I in that movement? Probably on the outskirts of it,” he says. “I wasn’t really a participant. I mean, I never did acid. I think I smoked a joint once or twice. My sister was a bit more involved. But I was never more than sort of hippie-adjacent: I had long hair, I was a surfer, stuff like that.”

I suppose surfing makes sense for a child born in the US Virgin Islands. Grammer’s father was a musician, restaurateur and magazine editor, his mother a dancer, actor and Republican activist. They divorced when he was two years old, and he was raised back on the US mainland by his mother and two maternal grandparents.

Sometimes, during our conversation, Grammer seems to toss out phrases with authoritative nonchalance. Other times, this gives way to a kind of soft-spoken earnestness. “I’ll defend everyone’s right to be passionate about what you might consider an alternative lifestyle,” he says, reflecting on the hippie movement. “But living a life of faith is probably a pretty good alternative lifestyle too.”

He describes one particular moment when he was a teenager growing up in Pompano Beach, Florida, and was approached on the shorefront one evening by a couple of “really, really beautiful girls”. They asked him: “Have you met Jesus?” “And I thought, ‘Well, I think I have, honestly.’ That’s how I felt,” Grammer recalls. “And of course, they were so lovely and positive, and I was a teenage boy. It was tempting. But I didn’t end up going with them because I didn’t think I needed to be reborn. I thought I was already there. But then, of course, life threw a few things at me that I didn’t know how to handle.”

This last sentence has the ring of understatement. Across the first three decades of his life, Grammer was blindsided by a series of terrible and unlikely tragedies. In 1968, his father, Frank Allen Grammer Jr, was murdered in a home invasion. In 1975, his 18-year-old sister Karen was kidnapped, raped and murdered. In 1980, two of his half-brothers died in a freak scuba-diving accident. To suffer any one of these adversities would be horrific; piled atop one another, the effect is unimaginable.

After the challenges I came across, I turned my back on God for a good chunk of [my life]. But in a kind of belligerent way, I was still looking for God to help me— Kelsey Grammer

In light of this, it’s all too understandable that Grammer went off the rails. In 1988, when he was starring in Cheers, he was arrested for possession of cocaine. His drinking and drug use would continue to worsen throughout the 1990s. His romantic life was turbulent; he was married three times before tying the knot with his present wife, Kayte Walsh, in 2011. Midway through the third season of Frasier, in September 1996, Grammer flipped his sports car while driving in Agoura Hills, California, where he lived at the time. He narrowly escaped grievous injury, but the incident prompted his Frasier colleagues to stage an intervention; he has been sober since.

“After the challenges I came across, I turned my back on God for a good chunk of [my life],” Grammer says. “But in a kind of belligerent way, I was still looking for God to help me. Because when the really bad moments came up, I still remember calling on the God of my childhood for help.

“I didn’t get an answer right away,” he continues. “Throughout my life, I held myself at a distance from the idea that there is purpose in life, and love that is everlasting. I no longer have that resistance.”

Grammer’s sister is on his mind a lot at the moment; he is currently writing a memoir about her, and he has, over the past few years, been summoned to speak at her murderer’s parole hearings several times. “For a good chunk of my lifetime, that was not part of my life,” he explains. “But since about 12, 13 years ago, I have been speaking at these hearings.” According to Grammer, these parole hearings are part of “a system that’s being gamed a little bit” by the murderer and his lawyers. “I think they just keep hoping that one of these days the parole board will simply say, ‘Oh, he’s done enough time. It’s OK, let him out.’

“Of course, that would be a real challenge for me,” he continues. “But I’m trying to be honest with you about the upside of it... What I found in my life – with the sort of resident malaise that lives in my soul because of some of the things that happened – I have found that in those moments, Jesus is actually more present, more apparent, more readily available than I realised.”

Grammer says he came to this conclusion when he was standing on a baseball field a while ago, and asked God: “Where were you?” “The answer came: ‘I was right there.’ I do think that when things are at their worst, that’s when Christ is closest.”

Religion was seldom addressed overtly in either Frasier or Cheers (with the exception of waiter Carla Tortelli’s superstition-peppered brand of Roman Catholicism). But both series – and especially Frasier – were absolutely, maybe even principally, concerned with ethics and morality. Frasier’s irrepressible conscience was, in many ways, what tempered his pomposity and made him a truly compelling protagonist. “The ethics of Frasier – the study of good, let’s say – was important to us,” Grammer remarks. “It seemed important to all the people that were involved in the original one, and it has remained important in the show today.”

He goes one step further: “Frasier has been my ministry, you could say. He’s trying to spread the good word, to put some love in the world – and tolerance, true tolerance. Those are powerful words, but most people use them to manipulate. I think tolerance is a beautiful, beautiful concept. Not particularly realised in behaviour in our country, but still a good goal.”

In the US, religion and politics often march hand in hand; that Grammer is a card-carrying Republican would seem to some to be a natural extension of his Christian beliefs. But it isn’t necessarily that simple. “I’m not sure that my faith informs my political beliefs,” he says, “but I do believe this: ‘Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s, and render unto God, what is God’s.’ So I’m sort of on that team.”

I don’t believe Republicans are evil, awful people. I don’t believe Democrats are. I believe that I’m a liberal, but leftism is the new faith for people who are faithless— Kelsey Grammer

He builds a head of steam. “The political world is necessary. I get it. There is a very strange, and wonderful maybe, creature that wants to run everything. And they’re gonna try to do everything they can to take all your money away from you, and tax the heck out of you, and make you think the way they want you to think. And God bless them.”

With a kind of playful cynicism, Grammer quotes the final line of Troilus and Cressida, in which the impish Pandarus says: “I bequeath you my diseases.” “That’s a political response to a series of horrible questions about what happens in the history of man and what we do to one another,” Grammer explains. “But these diseases tend to populate politics. And I leave it to them.

“I don’t believe Republicans are evil, awful people. I don’t believe Democrats are. I believe that I’m a liberal, but leftism is the new faith for people who are faithless. So I don’t spend a lot of time on their side of the equation, because I just don’t believe the government is the answer to all things.” As a faithless, tax-loving leftist myself, I fight the impulse to counter Grammer’s argument. There are some ways, maybe, in which I fear he has a point. Or maybe his famous oratory flair has simply worked its magic.

Outside of Frasier, Grammer’s most enduring role came as a voice actor, playing the mop-haired criminal clown Sideshow Bob in The Simpsons. I can’t help wondering if there’s an irony to Grammer’s involvement in a show that, in its pomp, ruthlessly satirised organised religion. “Listen,” Grammer chuckles. “Religion can handle it. You can measure periods of our contemporary history where it maybe seemed like Satan got a foothold for a while – I think we’re going through one of those periods now, possibly – but somehow God always tends to work it through somehow.

“The idea of lampooning – or even harpooning – popular ideas is the father of comedy. And it’s a cartoon, so you don’t really mind hearing silly extreme views come out of different people’s mouths.”

Grammer has to go; morning TV beckons. But first, I ask about the Frasier revival. The modern pop culture landscape is littered with underwhelming reboots, rehashes and spin-offs – what makes this new Frasier any different? “This isn’t really a spin-off,” Grammer replies. “It’s more of a third act, or fourth act. A spin-off of a spin-off.”

Seemingly absent from the revival are Hyde Pierce, British actor Jane Leeves, who played Frasier’s housekeeper Daphne, and, of course, the late John Mahoney, who played his retired father. Bebe Neuwirth and Peri Gilpin are both set to make guest appearances, reprising their roles as Frasier’s frosty ex-wife Lilith and street-savvy radio producer Roz respectively.

But it is mention of Grammer’s new co-stars that gets him talking most effusively. These include Only Fools and Horses’s “magnificent” Nicholas Lyndhurst – who became a “great, great friend” while acting (and singing) with Grammer in a 2019 production of Man of La Mancha at the London Coliseum – and Jack Cutmore-Scott, who plays Frasier’s adult son, Frederick.

“At first, you cast these people, you’ve never seen them before. And boy, by about the middle of the second show, I thought, ‘Son of a gun. He’s actually doing it. He’s like Frasier’s kid. Wow.’ So I think it’s gonna be a great discovery for people. There’s some new people on the show to really fall in love with, and arguably” – Grammer’s voice drops a few decibels – “it may even be funnier.”

Like most Frasier and Cheers fanatics, I know better than to get my hopes up. But as Grammer sits there beaming into the webcam, it’s hard not to believe him.

‘Jesus Revolution’ is out on 23 June. More information about the film can be found at jesusrevolutionmovie.co.uk