In a rental car with broken air conditioning, somewhere south of L.A. on the 405, as afternoon temperatures rise, misery begins to take hold. Kelly Slater, in the passenger seat, has been talking about aerials: When he was 10, he saw someone catch air on a surf video and his mind exploded. That’s pretty standard stuff in surfing today, but back then, he points out, it was rare. Young Slater had no idea how to finish; he just zoomed up waves and launched, departing his board, taking flight with no plan in mind. “Why do that if you’ll never land it?” his dad asked. “One day I will,” he replied.

Now, though, he’s sweating. “I can’t take it anymore, man,” says Slater, who started this drive in sneakers, sweatpants and a hoodie. And then, there go the pants. That’s how he ended up riding shotgun in his boxers. Amid a series of emotional conversations, the metaphor has written itself: the world’s greatest surfer, laying himself bare.

It’s been a long day. Around 5 a.m. on March 25, Slater and his girlfriend of 14 years, Kalani Miller, loaded three surfboards, three massive suitcases and two carry-ons into a separate car at their house in Cocoa Beach, Fla., drove an hour to Orlando, flew to L.A., loaded up the rental with the busted AC and headed to Beverly Hills. Now they’re due south, toward a second home in San Clemente. Miller is napping in the backseat and Slater is yawning, resting his head on a hand beside an open window. Ready for home. See the dog, eat some food, rest. Another day in the life.

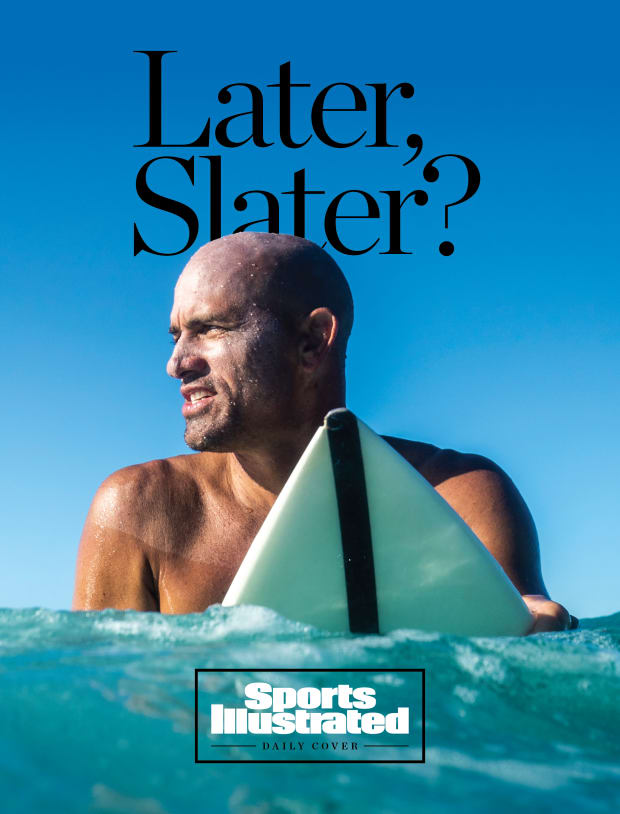

Todd Glaser

Slater is packed for two weeks in Southern California, followed by a month in Australia. He’s been around this sport for 40-odd years, but still he’s competing on the World Surf League Championship Tour, where he’s claimed 11 world titles, including once as the youngest winner ever (at 20) and once as the oldest (39). Along the way, through relentless success and the kind of charm that landed him a recurring role on Baywatch, he helped take surfing mainstream. Some would argue that he’s accomplished more in his sport, and done more for it, than any other athlete across time. “I don’t care who you mention—Michael Jordan, Muhammad Ali,” Mark Richards, himself a four-time world champion surfer, once told Sports Illustrated. “Kelly is unquestionably the greatest athlete ever to stomp around on this planet.”

On this trip Slater will stand next to two of the few people who might realistically have a bone to pick with Richards: At the Oscars he gets onstage and presents a James Bond video tribute alongside skateboarder Tony Hawk and snowboarder Shaun White. (“Surreal,” Slater says of an evening that will trend on Twitter for days.) In this tribe of GOATs, each of whom has forced his once-fringe obsession into the forefront of American culture, one thing differentiates Slater: While Hawk (who’s 54) and White (35) have retired from competition, Slater’s still at it.

In late January he started yet another season on the tour, beginning with the Billabong Pro Pipeline, held on the North Shore of Oahu. Although surfers compete to add up points in pursuit of a world title, each location on the tour carries its own significance, and Pipeline is a Super Bowl–level event.

That comes down to the nature of the surf. Many competitions feature long rides on smooth waves, allowing riders stylish cutbacks, slashes and aerials until they disembark with grace. If the waves allow and you catch a barrel, disappearing into the tube formed by a cresting wave, all the better.

Pipeline, though, is different. Swells rise and fall fast and hard. They arrive sometimes 20 feet tall, crashing with violent force, landing like bombs. Here, the barrel is the way. Catch your wave, drop in and make it out before the ocean swallows you. Most rides end with surfers vanishing into explosive foam and chop, with sharp coral reef waiting below. Here your arena is an obstacle, but also a teammate that you can neither predict nor control.

Slater began this year’s competition having not won the weeklong event in almost a decade. In fact, it had been five and a half years since he’d won any competition—four since he thought about retiring for good, after shattering his right foot in South Africa’s Jeffreys Bay. And now Slater faced adversaries less than half his age. His finals opponent, 24-year-old Seth Moniz, was the son of a man Slater had surfed against two decades ago.

And Moniz was good in Oahu. But Slater, the master, was better, catching barrel after barrel. Near the end of his heat he snagged his biggest wave of the day, plummeting from the upper lip into the barrel like a man off a cliff—as if, he says, “I fell out of the sky.” He thought the crest would clip him, but the tube curled over instead. He would later call the moment “spiritual,” the ocean giving him something.

Todd Glaser

Emerging afterward, Slater held his face in his hands and fell back into the ocean in ecstasy as time expired, knowing victory was his. Moniz embraced him in the water. On the shore, fans and opponents lifted him onto their shoulders. He popped champagne. He kissed Miller. He cried in his post-heat interview. He was No. 1 in the world for the first time in eight years.

That was Feb. 5. He would turn 50 within a week.

Six weeks later, back home in Cocoa Beach, the afterglow lingered. Slater was staying low key, playing some cards and some golf, visiting family and friends, cooking with Miller. But he could still feel the high from Pipeline. “The whole thing was like a dream,” Slater says one night from a back porch overlooking the Banana River. “It seemed like somebody wrote a script and put me in it.”

In the aftermath, Slater got a congratulatory text from Tom Brady, a friend of 15 years who himself has found some time to surf between Super Bowl wins. In the middle of his own brief retirement at the moment, Brady, whose longevity has been talked about as much as any athlete’s ever has, found himself in awe. “At 50 years old, accomplishing what he did—it was mind-blowing,” says Brady. “No one ever imagined that.”

And that’s from a 44-year-old football player. To dominate so late in life at surfing (or skateboarding) is perhaps even more mind-blowing. “Our sports continue to evolve,” Hawk, another friend, points out. “They’re so artistic and subjective. The levels keep getting pushed further and further. For Kelly to be able to adapt to that is really the most impressive thing.”

Slater, today, is weighing whether this will be his own final tour. “I’ve put so much time and effort into this thing over the years,” he says. “And it’s great; I love it. But also: Sometimes I just want to get away. . . . That’s gonna be fun for me, to watch everyone else deal with these pressure situations and close heats. The thrill and agony of it all. I can feel that fire burning out.”

In at least one way, facing the end is like facing the beginning: Slater isn’t sure what will happen next. “At some point,” he says, “I’ll get too old to get the results [I want]. But I don’t think that’s yet.”

The fire burns low, but it still burns. Seeing friends forced to move on, Slater, for now, feels compelled to use what he still has. He describes playing golf recently with Drew Brees, who retired in 2021 after 20 years in the NFL. “He was like, ‘Man, I miss it,’ ” Slater says. “ ‘I miss that fire.’ ”

A life like that, without the fire, sometimes feels appealing to Slater. “I kind of look forward to it,” he says.

Todd Glaser

But then there’s the matter of that thing inside of him that keeps the fire going—the thing that got him here. “I really think that to be a great competitor,” he says, “there needs to be some kind of personal glitch.”

Brady knows about it, even if he doesn’t understand it. “There’s something that has allowed us to get to the point we’re at,” he says. “And unfortunately, we’re not necessarily in control of that.”

“I just get consumed by it,” says Hawk. “And that can be a curse, for sure.”

Brady: “I think that’s the hard part. I can’t turn it off. I don’t think [Kelly] can turn it off. And that’s hard. You just gotta manage it the best way you can.”

Hawk: “There’s a price to pay. A price to pay with your body, the long-term effects. And the idea that when you have to, how are you going to let this go?”

That’s the question for Slater, a man who describes the ocean as a “canvas” and who says surfing is “about something deeper about yourself, an expression of your soul.”

How?

Slater’s glitch was born when he started surfing in Cocoa Beach as a boy, the waves offering escape from a turbulent home, elements of which he says shaped him into “a competitive beast.” A father who struggled with alcoholism; a funny but, Kelly says, often harsh mother; an angry older brother. “If I win,” he recalls thinking, “it’ll fix stuff.”

Slater would stare up at the Pipeline posters on his walls and study the waves in magazines and on videos. But when he got his first chance to confront them, at 12, he was overwhelmed by Pipeline’s monsters. A wave, he says, slammed him into the water, against the reef beneath, pinning him under his board. All he could do was hold his breath until the ocean let him up.

A few years later, undeterred, Slater moved to the North Shore—this was where you made a name for yourself. But many days he just sat on the beach, watching the Pipe waves, “stuck with fear” as he studied them and the brave souls who tried to tame them. “Surfing’s a calculated risk,” he says. “There’s danger and there’s skill, and you figure out where those two things intersect.”

Todd Glaser

That, and you “eat s--- a bunch of times.” Slater remembers a trick an old friend taught him: Laugh at the waves. “Get rid of the fear,” he says. “Understand what the wave is going to do. And become part of it.”

That was the way. Become part of it. And he found that to do that, to know the ocean, he had to know himself. “You’re dealing with a lot of unknowns,” he says. “But there is a pattern in the ocean. Yes, there is some kind of luck—but it just seems like the more connected you are with yourself, the better luck you have.”

The world’s greatest surfer has a favorite mechanical engineer. Feels a connection with him. Slater has read several books about Nikola Tesla, famous for his breakthroughs around electric power, and what stuck with Slater is that Tesla accomplished all he did despite crushing migraines that left him debilitated. “He realized,” Slater says, “that he was either going to control and understand [the migraines], or he was probably going to kill himself.”

Tesla, though, said he found power in those piercing headaches—visions that spurred, in the end, invention. Intense emotion, Slater says, “turned out to be his superpower.”

Slater says he, too, experiences emotions with a profound intensity, beyond the norm. Extreme highs and lows. Early on, those highs came with fame and fortune and that world championship at 20, clinched at Pipeline. It was a hell of a crest for a self-described redneck from the Space Coast. But the lows came just as heavy, one year later. He ended an engagement, he lost the world title and he found himself six figures in debt. He has never publicly shared the depths that his anguish reached, but emotionally he felt almost like he was pinned against the reef again. He says that one night he found himself at the edge of an apartment building’s roof in Coolangatta, on Australia’s Gold Coast, with a beautiful view of the eastern Indian Ocean. He remembers “just looking down . . . like this would all be over in a few seconds. That’s where my mind was. . . . I was suicidal for a minute.”

Thirty years later, he says: “That’s not something I want to identify with. . . . It’s just factual. I was in that state of mind. And once that thought creeps in your head, it can always creep back in.”

To quell this he says he tried therapy (but inconsistently at the time) and antidepressants (but he didn’t like how they numbed him). He cares too much about his body to escape into drugs, and he found drinking’s hangover a waste of time. Instead, in these peaks and valleys, he says surfing became a place to funnel those emotions, redirecting them toward the waves. “I learned how to focus and channel that energy [into competition]. It consumed me. I became really obsessive about it.”

Todd Glaser

In other words, he gave himself to surfing in total. Winning became his vice. “When I get past that intensity, I get really calm,” he says. “Everything becomes easy. I have a breakthrough, and then it comes out during my surfing. I understand how to tap every bit of a wave’s energy.

“The lows are almost like Tesla’s migraines,” he says. “[They] exaggerate everything in my life. I feel like that’s sort of my superpower. Ultimately, it’s probably why I’ve done what I have.”

When Brady texted his congratulations after the Pipeline win in February, Slater wrote back that it had been the best feeling—the greatest win—of his life.

“I really took that to heart,” says Brady. “I was like, Wow. Kelly feels like winning at his age, after all he’s won, this was the greatest one.”

A month later, Brady shocked the world, ending his brief retirement and returning to the NFL. That thing inside that drives him, he couldn’t turn it off. “I don’t think you want to,” Brady says. “I think it eventually turns off for you.”

After that twist, Slater texted Brees, who’s now 43. “C’mon man,” Slater joked. “We’re all doing it.” And he smiles remembering Brees’s reply: “ I’m starting to like it. I’m starting to get the hang of [retirement].”

Slater can imagine himself getting to that point. (Technically, he has retired before, in 1998, after his sixth world title. That lasted three years.) Of his famous friends, though, perhaps Hawk has the most realistic blueprint for what an exit might look like. The skating legend retired from professional competitions in 2003, but he keeps at it recreationally, out of the spotlight. The fire still burns, even after he broke his right femur in a skating accident in March. “I can’t let it go if I think there is a chance that I can get back out there,” he says.

“I will be [skating] as much as I can—it just might be behind the scenes, if I feel like my skills are fading. I don’t want to rot in public.”

As the rental car with no air approaches San Clemente, a marine layer rolls in over the ocean, providing sweet relief to a pantsless passenger. Later, after dinner at Miller’s family’s house, Slater falls asleep early on the couch, snuggled with his mixed-breed rescue, Action.

The next morning, Slater finds his way to a private gym in a garage tucked behind a neighbor’s home. He’s here to work out the pain. His shoulder muscles, often contracted forward from paddling on his board, require constant care. His hamstrings and quads need loosening. The foot that he shattered still throbs. Older injuries nag at his left heel and ankle, too. And he’s had scoliosis for ages, so his back muscles tend to bunch together, pulling on everything else. A long travel day in a rolling sauna has only exacerbated things.

Inside, two men administer aggressive bodywork over several hours: twisting, turning, stretching, rooting through stiff muscles and tissue. They use hands, elbows, knees and heels. A massage therapy gun. At one point, a muscled man laces up a pair of soccer cleats and walks across the back of Slater’s legs. Kelly writhes around, covering his face with his hands, arching his back and twisting away from them. “Oh, f---! God f------ damn it!” And they dig more.

One of Slater’s torturers smirks. “It’s not that bad, dude. Jesus.”

Todd Glaser

This is good pain, though. Within hours, nothing hurts anymore. “New man,” Slater says. “Just gotta have the balls to get some pain going.”

That’s made all the difference. Everyone has pain. Their paths are shaped by what they do with it. Later that evening, Slater is back in L.A., with friends at the SoHo House in West Hollywood, overlooking the lights below. Here he considers what separates people. He sees a sometimes blurry line between passion and vice, creation and destruction. Slater has lived 30 years since Coolangatta, in and out of therapy and other help, especially the last few years. “You spend the first decade of your life learning,” he says, “and then the rest unlearning.”

The big lesson has been simple: “I definitely have learned to be kinder to myself,” he says. “I used to have a really negative internal dialogue.”

He knows now, too, that for him there’s more to living than giving himself to his sport. There’s life after the last heat. “I don’t feel as much of a need for competition,” he says. “If the waves are good, life’s great. At all moments. It seems to answer everything for me.”

He can picture it. Surfing just to surf. Maybe he’ll taper off, a couple of competitions each year, then let it all go. “There’s a part of everyone that, when they quit, becomes a little empty,” he says. He does wonder, though, what might fill that void. “Maybe something could.” But he won’t know until he lets this go. “Not until [surfing]’s done.”

In may, Slater checks in from the Gold Coast. He has now finished outside the top 10 in four out of six competitions. On one hand, this is good practice in applying what he’s learned, to be kind to himself and to just have fun surfing. On the other hand, the fire burns a little hotter now. The call to see what you’re still capable of. “When you own it and you’re in the moment, there’s nothing better,” he says. “Pipeline this year, nothing can top that.”

Going back, on video, you can see that moment in real time in Oahu. It’s there, one wave before the end, when Slater makes it through a barrel with a rare window to throw a trick. Instead he goes full send, like he’s 10 again, back in Cocoa Beach, flying off the top of the wave and away from his board, no plans to land.