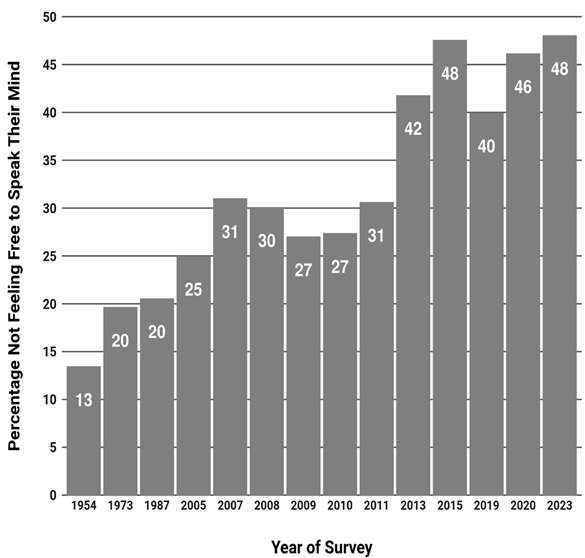

A very interesting new article, by Profs. James L. Gibson (Wash. U.) and Joseph L. Sutherland (Emory). Here's the key chart, updated to include 2023 data, gathered before the Oct. 7 Hamas attack on Israel (the 2023 data is credited to Peter Enns and Verasight):

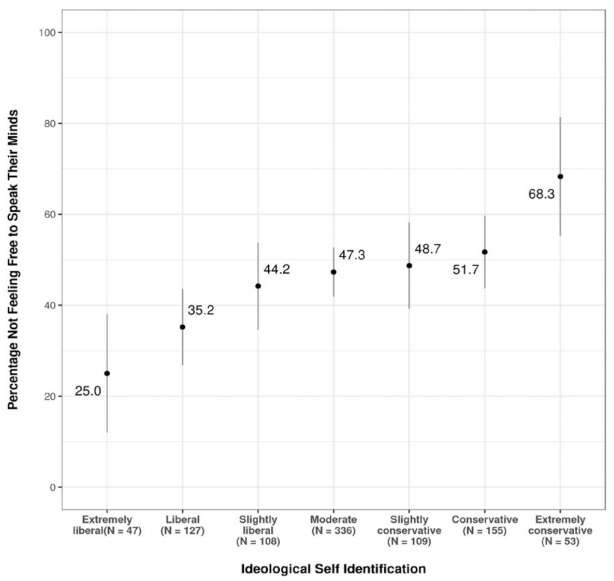

Here's the breakdown of the 2020 data by ideology (with the usual cautions about the small size of some of the subsamples, especially on the extremes, and the fact that different people will interpret vague terms such as "free to speak your mind" differently). What struck me is the magnitude of the felt lack of freedom among the three most moderate segments, even setting aside the different reactions on the extremes:

And here's an excerpt from the introduction to the article (read the whole thing here):

[A] large segment of the American people engages in self-censorship when it comes to expressing its views. We define self-censorship as "intentionally and voluntarily withholding information from others in [the] absence of formal obstacles." In an influential study, Michael MacKuen refers to this more simply as deciding to "talk" or "clam." …

In a nationally representative survey we conducted in 2020 (see Appendix A online), we asked a question about self-censorship that Samuel Stouffer first put to the American people in 1954: "What about you personally? Do you or don't you feel as free to speak your mind as you used to?" While we readily acknowledge that there are a number of potential frailties with this item, its utility is that the same question has been repeated over a number of surveys between 1954 and 2020 (Appendix C addresses several potential threats to the validity of the indicator, concluding, generally, that like many, if not most, analyses of change in public opinion over time, the value of investigating how responses to the query have evolved exceeds the limitations of the question)….

While some might understand these data to indicate that those with "bad" views are no longer free to express themselves, which may be a good thing, we have no means of discerning whether the speech lost is "good" or "bad" speech. Owing to the benefits of deliberations among citizens for democratic politics, most democratic theorists would regard these results as too important to ignore….

What accounts for this remarkable loss of perceived freedom in the United States? How is it that four in ten of the American people do not feel free to express themselves today? Is this loss of free speech a function of fear of being misunderstood by friends and colleagues, or are the causes more systemic, such as government surveillance of social media, telephone, and email discussions? Is the explanation associated with a culture of "political correctness" that many conservatives rail against, or is the source even more elementary, reflecting little more than growing political polarization and incivility, as well as increasing political intolerance in the country? …

Our purpose in this article is to explore several hypotheses about the correlates of self-censorship at the aggregate and individual levels. Our analysis here is assuredly not comprehensive or definitive, but in light of the presumed importance of unbridled political discourse for the health of democracies, our findings raise many troubling issues for American democracy. Our most imperative objective in this article is to use these provocative results to spur additional research on why people seem to have learned that keeping their mouths shut is the best thing to do.

To be clear at the onset, our analysis makes few claims to causal certitude in the relationships it investigates…. Our cross-sectional analysis is particularly vulnerable to causal doubt (although most demographic attributes are unlikely to be consequences of political attitudes, for most people). We contend that determining what goes with what, and what does not go with what, is a valuable first step in understanding how and why people engage in self-censorship.

The post "Keeping Your Mouth Shut: Spiraling Self-Censorship in the United States" appeared first on Reason.com.