In most of the world, people and governments take pride in their historic railway stations. They invest time, money and effort in conserving these old buildings because they see them as valuable public assets that help give a city or town its sense of place, beauty and identity. If officials want to tear down an old station, people march in the streets.

When Manhattan's magnificent Pennsylvania Station was bulldozed back in 1963, it generated an international outcry, sparked an ongoing conservation movement throughout America, and prompted New York City to pass a landmark preservation law. That's why Grand Central Terminal, which had also been slated for the wrecking ball, remains grand today.

In Thailand? Not so much. We do have a rich railway history, which began in 1880, and flourished hugely during the reign of King Rama V and after. But many beautiful and important stations have been demolished. Today, there are 446 public railroad stations nationwide and a special station for royal use at Chitralada Royal Villa in Bangkok.

Most were built between 1890 and 1950. At least 200, perhaps as many as 300, deserve to be protected for their architectural, aesthetic and historical value. Most are local landmarks. All are owned by the public via the State Railway of Thailand (SRT), a state-owned enterprise, which manages them on behalf of all of us as citizens.

Yet despite the value to our society of these assets, the SRT has allocated no budget to conserve them. It has no systematic plan for conserving heritage. It lacks heritage conservation professionals, expertise and operations. It has no inventory of the public heritage under its management. There is little public information, public discussion or public involvement regarding this heritage. The SRT treats these public assets as its own property.

Worse, most stations are slated for demolition under the SRT's plans to double-track its lines across the country. To be sure, double-track lines are greatly needed. But some stations can continue to be used. Most can be relocated since they are made of wood. For about 1 million baht, a station can be easily disassembled and put back up again on a new site nearby to benefit the public as a civic centre, meeting hall, museum, library or performance space. You name it.

To its credit, the SRT is willing to let others do the job. It does allow local communities to organize their own conservation efforts, but they have to do it all themselves, with their own funds. A few stations have been preserved this way. Some of them have won recognition from the media and the Association of Siamese Architects under Royal Patronage.

But most communities lack money and organization of their own. That's why the SRT needs a national heritage conservation plan, guidelines, budget, staff and proactive approach, with lots of involvement by the public. The SRT will invest many hundreds of billions of baht in the coming five years. By investing just 300 million baht, our railway heritage resources could be saved, enriching our quality of life for generations to come.

Besides the hundreds of railway landmarks and hidden gems all across Thailand, Bangkok itself has two major historic sites that need conservation. Hua Lamphong Railway Station, or Bangkok Station, opened in 1916, a few years after Penn Station. It still stands. But most services are being diverted to the new station on the outskirts of the city centre. The SRT has proposed a massive commercial redevelopment project that would stockade the old station and its neighbours between towers of glass.

The Makkasan Factory District was first established in 1910 in the heart of Bangkok. It includes a railway station, depot, workshop, warehouses and worker residences, with dozens of big old trees. This resource is threatened by the SRT's plan to let a major corporation build a huge multi-use complex there. Part will be a park, but plans to conserve the railway heritage are unclear.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Makkasan was Southeast Asia's largest train manufacturing facility, and many old buildings and machines are still there. With a better plan, this site could become a treasure for the city, with a museum and other facilities that would serve the public. The site could become a much-needed green "lung" for Bangkok, like the marvellous new Benjakitti Forest Park.

Since 2010, in my capacity as a concerned citizen and as an academic, I have been studying Thailand's railway heritage, gathering old government records, books, photographs and architectural blueprints. And I have been working with others to help care for the sites: local communities, government officials, architects, media professionals and NGOs. Many SRT officials and former railway workers themselves are especially keen on this history, which is cause for hope.

In 2016, when 16 old railway stations were threatened with demolition, I wrote to Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha, and urged that they be saved. In the end, thanks to joint efforts by individuals, local communities, officials and businesses, 13 of these charming stations were conserved, including Nong Maeo Railway Station in Nakhon Ratchasima province, built in 1929 and today a Thai traditional medicine centre.

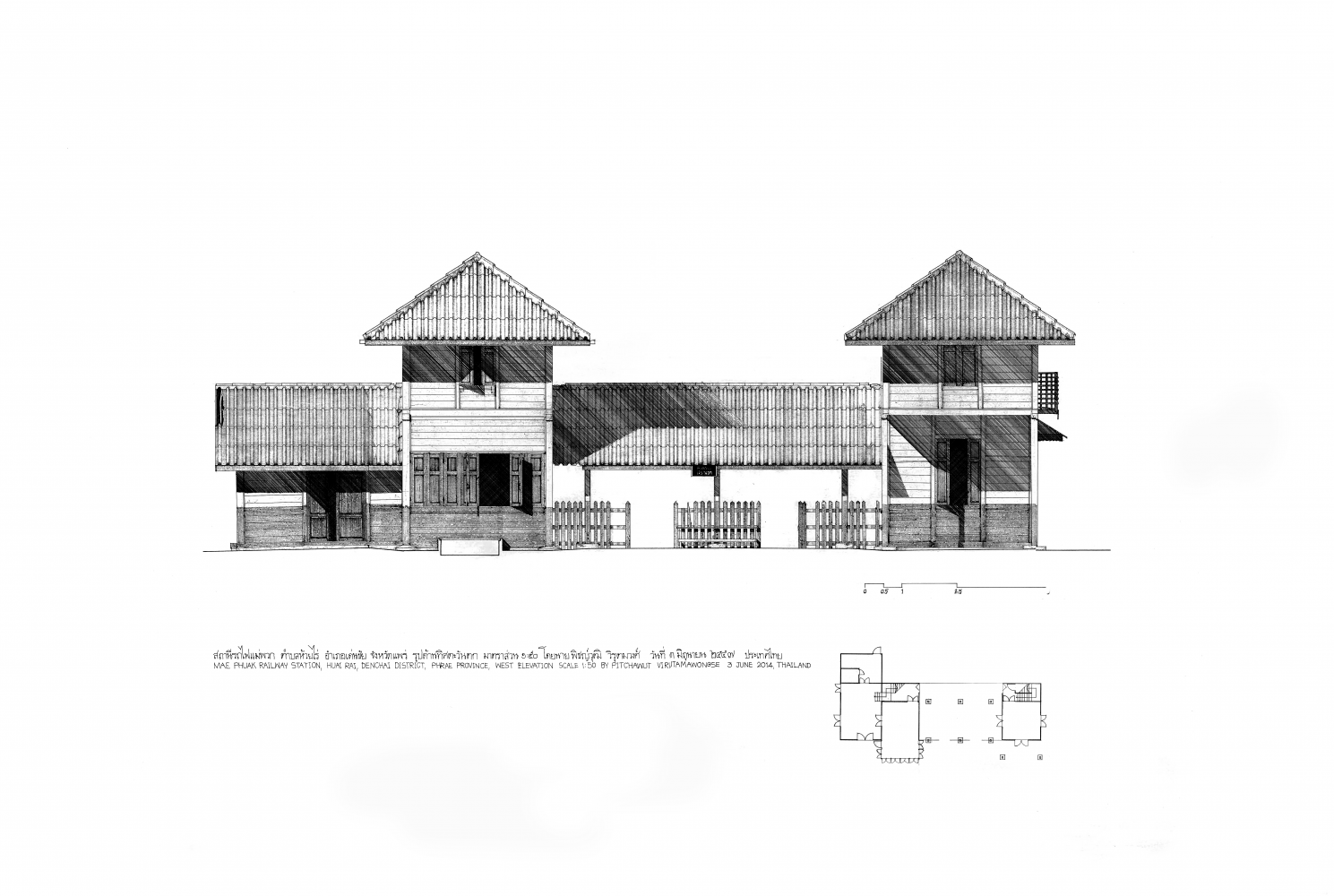

A few other sites have been saved and live on to serve their communities. For example, the Bavarian-style Ban Pin Railway Station finished in 1914 in Phrae province. The Mae Phuak Railway Station, also in Phrae, opened in 1919 and in 2015 was conserved as a museum, which won a national conservation award a few years ago. This proves that Thais love this heritage and want it to be cared for.

Since the SRT was set up as a state-owned enterprise in 1950, it has accumulated some 100 billion baht in debt, incurring high annual interest costs. Of course, this debt is not just "red ink". The SRT has served the public interest by providing affordable service for transporting passengers and cargo, supporting development of the economy. Fares remain below the cost of providing service, so to pay off its debts, the SRT is becoming a de-factor property developer, leasing out parcels of its vast land holdings all around the nation. Tens of billions of baht will flow in.

But the conservation of train stations and the old communities around them should be integrated into this money-making effort so that we don't end up with projects that mostly benefit developers. Heritage sites should be conserved and respected to strengthen the economic and social well-being of local communities. Let them enhance civic pride, tourism, learning and quality of life. Railway heritage can help keep Thailand on track to a better future.

Parinya Chukaew is associate professor of architecture at King Mongkut Institute of Technology Ladkrabang. Heritage Matters is a monthly column presented by The Siam Society Under Royal Patronage to advocate sustaining the architectural, cultural and natural heritage of Thailand and the neighbouring region. Each column is written by a different contributor. The views expressed are those of the author.