The political scene in Bihar has lately been marked by a contest between key players competing for the legacy of the socialist icon Karpoori Thakur. The two-time Bihar Chief Minister championed the principles of social justice and advocated for equal rights for the marginalised, embodying the ideals of “azadi and roti” – freedom and sustenance for all, which earned him the epithet of ‘Jan Nayak’ (people’s leader).

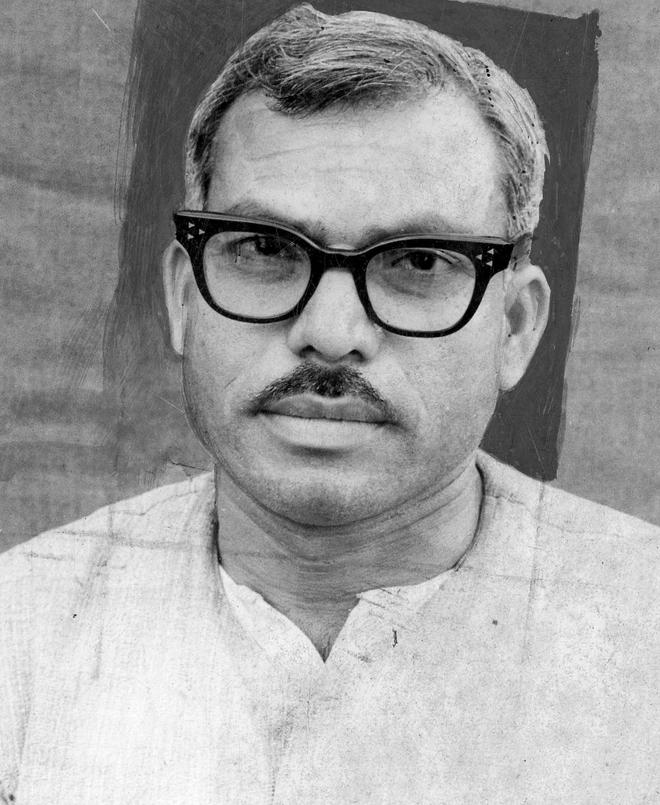

Known for his honesty and simplicity, Mr. Thakur, himself belonging to a minority caste, led subaltern classes across castes in his political career to emerge as a significant figure in the struggle against social discrimination.

The posthumous awarding of the Bharat Ratna, the nation’s highest civilian honour, to the “beacon of social justice”, as PM Narendra Modi has called him, in the run-up to the Lok Sabha elections has introduced a new element to an already politically charged atmosphere. An ongoing political battle to leverage the leader’s legacy and a recent caste survey which revealed that backward classes constitute the largest social group in the State show that Mr. Thakur’s policies still resonate in contemporary Bihar politics.

Mr. Thakur’s political career, spanning four decades from the 1940s to the mid-1980s, included two stints as the Chief Minister and one as the Deputy CM when he was unable to tide over internal rivalries.

His administration ushered in transformative policies, including the reservation for backward castes— a move that pre-dated the Mandal Commission, quota in jobs for other backward classes (OBCs), abolition of alcohol and the removal of English as a compulsory subject for matriculation. He mentored a generation of leaders like Nitish Kumar, Ram Vilas Paswan and Lalu Yadav who have adopted Mr. Thakur’s legacy in various ways.

Also Read | In choices for state honours, Modi government often reaches across the political aisle

A life of contrasts

Karpoori Thakur’s humble beginnings eventually shaped his politics of social justice. He was born into a poor family in Rajput-dominated Pitaujhiya village, later renamed as Karpoori Gram after him, in Samastipur district on January 21, 1921. His family hailed from the ‘Nai’ samaj (barber community), an Extremely Backward Class (EBC) among the OBCs that held little political influence at the time.

Like many other young people, Mr. Thakur was drawn towards the Indian Independence movement, but his entry into public life happened at the age of 17 when he was invited from the audience to address a kisan sammelan or peasants’ conference near his village. From peasant movements, he moved to student politics, but left college without completing his Bachelor of Arts degree due to his active involvement in the freedom struggle.

He was imprisoned during the Quit India Movement. It was in jail that he was exposed to the ideas of socialism, due to his acquaintance with leaders of the Congress Socialist Party. He quit the Congress Party in 1948 to join the socialist movement and the Socialist Party. Mr. Thakur drew inspiration from Dr Ram Manohar Lohia, who appointed him the party secretary.

He was elected to the Bihar Assembly in 1952 in the first election held after Independence. Dr Lohia’s death in 1967 marked the beginning of the second phase in Mr. Thakur’s political career, as he solidified his identity as one of the tallest backward caste leaders in the State. Mr. Thakur remained a committed socialist outside the legislature and served the people of Bihar as a Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) till his death on February 17, 1988, barring the one time he was elected to the Lok Sabha in 1977.

He held the position of Chief Minister of the State on two occasions. His term as the first non-Congress socialist CM of Bihar lasted from December 1970 to June 1971. He served his second stint from June 1977 to April 1979.

Mr. Thakur suffered only one electoral setback in his decades-long career: when he was defeated in the 1984 Lok Sabha polls, following a sympathy wave in favour of the Congress after Indira Gandhi’s assassination.

The politics and policies of Karpoori Thakur

Regarded as a pioneer of social justice in North India, Mr. Thakur aimed to represent the deprived sections of society. His reformative policies were shaped by the vision of socialist politics; there was a special focus on employment, reservation and language.

He is best remembered for introducing reservations for the backward classes in Bihar, the foundation of which was laid by Dr. Lohia in the 1950s. The economy was on a downward spiral, stirring discontent among the people in the Hindi belt towards the ruling Congress. Mr. Thakur presented the socialist ideology as an alternative to the masses and managed to unite the backward classes on the issue of reservation. Reservation became the primary agenda of socialist politics and Mr. Thakur employedthe issue as the main poll plank to emerge as a popular backward-class leader in the mid-1960s.

In 1978, the Thakur-led government implemented the recommendations of the Mungeri Lal Commission (1971-1977), introducing reservations for backward classes in government jobs and educational institutions in the State, much before the Mandal Commission changed political dynamics of the country forever. By what is now known as the ‘Karpoori-Thakur formula,’ the Commission reclassified backward classes and provided for a layered reservation system with 26% reservation in the government services. Of the total quota, 12% was given to the OBCs and a sub-quota of 8% to economically backward castes, women were given 3%, while economically backwards individuals from upper castes got 3%.

Before this, in his first stint as the CM, Mr. Thakur implemented an employment policy in response to the jobs crisis of the 1960s, whereby his government provided jobs to unemployed engineers. Around 8,000 unemployed engineers got jobs in the irrigation department of the Bihar government at the time, writes Professor Jagpal Singh in a 2015 paper.

He abolished land revenue for holdings up to five acres for the welfare of farmers. He was also committed to providing equal opportunities and bringing the marginalised to the mainstream. He waived school fees and provided free books to certain classes.

Mr. Thakur believed that the “foreign language” English should go so that those who are unable to access it aren’t excluded from public life. He removed the requirement to mandatorily pass in English at the matriculation level when he was the Deputy CM and Education Minister in 1967 — a rule that exists to date. He even launched a campaign called ‘Angrezi Hatao’, with the slogan ‘Angrezi mein kaam na hoga, phir se desh ghulam na hoga [There will be no work in English; the country won’t be enslaved again]’. This language policy was an outcome of the anti-English movement led by socialists in the 1960s in the Hindi belt of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

Another radical policy implemented by Mr. Thakur which sparked debate was a ban on alcohol in Bihar in the 1970s. His decision was, however, overturned by the subsequent government.

The old gives way to the new

Mr. Thakur’s policies won him accolades and brickbats. The quota introduced by him polarised the State as well as the socialist movement along caste lines, while his language policy divided the politics along the class and rural-urban axis. Professor Singh argues that Mr. Thakur implemented these policies in a hurry and contrasts his decisions with his contemporary counterpart, Devaraj Urs of Karnataka. Mr. Urs once remarked that “Karpoori Thakur climbed into the ring before he learned how to box,” when asked about Bihar’s reservation policy.

The local leadership of the Jana Sangh section of the Janata Party openly voiced its opposition to the reservation for backward castes, leading to personal attacks against the CM. The tensions led to the rise of anti-reservation protests which turned violent and posed a law and order problem.

In the meantime, differences grew between socialists and Jana Sangh’s leadership at the national level. Professor Singh writes that the embittered relations resulted in high caste individuals and Dalits joining hands against the OBCs and the Thakur government. The situation worsened following the Dalit massacre in Belchi and communal riots in Jamshedpur. In April 1979, the Jana Sangh finally withdrew its, support, leading to the fall of the Thakur 2.0 government.

A new and stronger OBC leadership, which had been mentored by Thakur, pushed him into the corner and replaced him with Anup Yadav. From once enjoying support from all castes in the State, he was forced to seek an alternative support base. Professor Singh suggests that Mr. Thakur’s proposal to arm the Dalits and the poor highlighted his political vulnerability at the time.

Mr. Thakur persisted in his efforts to bring together the most backward classes until he passed away on February 17, 1988. In an inaugural lecture for the Eklavya Jayanti Samaroh, a mere three days before his death, Mr. Thakur had emphasised the importance of a collective organisation for ensuring justice for excluded groups.