More than a decade ago Kara Goucher, a two-time Olympian, World Championship silver medalist and renowned marathoner, left the famed and secretive running team at Nike coached by Alberto Salazar: The Oregon Project. She didn’t say much at the time about her reasoning. Since then, stories that shocked the running world have come to light about Nike and Salazar, exposing harassment, abuse, doping violations and discriminatory maternity contracts.

Many of the details of what exactly happened with The Oregon Project, Salazar and Goucher have remained shrouded in an air of mystery. Until now.

In 2015, Goucher spoke to the media about her experience being pressured by Salazar to take a thyroid medication she wasn’t prescribed as a way to lose weight. She later cooperated with the United States Anti-Doping Agency case that resulted in Salazar’s four-year coaching suspension for doping violations, then detailed some of her experience about her Nike contract being suspended while she was pregnant and recovering from childbirth to The New York Times in ’19.

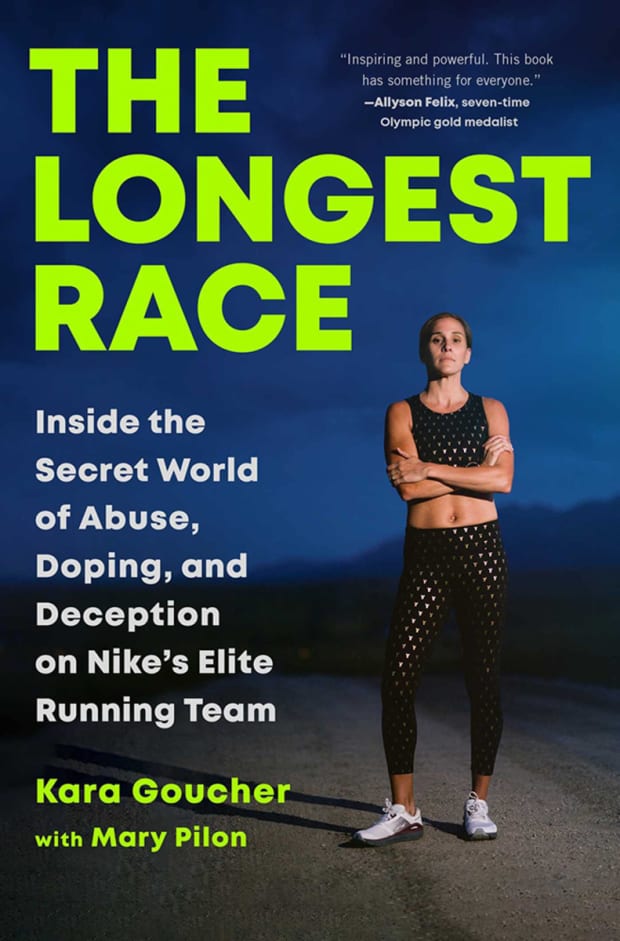

Goucher is finally telling the whole story of her experience at The Oregon Project in her book The Longest Race, written with sports journalist Mary Pilon. Other runners who have worked with Salazar, like Mary Cain and Amy Begley, have spoken up in recent years about the emotional abuse and harassment, especially around the obsession he seemed to have with his women runner’s weights. But no one publicly revealed that they were the athlete who described sexual abuse by Salazar that ultimately earned him a lifetime ban from SafeSport. In her book, Goucher reveals she was that survivor—assaulted by her coach multiple times during sports massages. She writes in the book that Salazar also drank heavily, sometimes even during training sessions; pushed medications and supplements on her that she didn’t need; made crude comments about her body, breasts, butt and weight regularly; and watched her while she sat, topless (by his recommendation) in the cryo chamber recovery unit they used after workouts. Salazar denies all of the allegations.

Reading the years-long account of Salazar’s emotional abuse and isolation of Goucher—who was the only woman on the team for most of her time there—is not easy by any means. But the details around how sexual and emotional abuse can be so expertly intertwined to convince victims not to seek help, and even question their own experiences, is a chilling, but necessary story. Below, Goucher discusses her book, what prompted her to come forward, her message to others who may find themselves in a similar situation and more. The following has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Helen H. Richardson/The Denver Post/Getty Images

Sports Illustrated: The book is a difficult read because your experience at The Oregon Project, and with Alberto Salazar specifically, was so full of abuse, coercion and secrecy. And so I can only imagine what it was like to live through. Much of this happened more than 10 years ago. Why did you decide that now was the time to tell this whole story together, as a book?

Kara Goucher: I felt like there was a lot of misinformation out there about what happened in my life and the team that I ran for. And I felt like the best way possible for me to talk about it would be through my own voice without someone interrupting me. As far as some of the more personal things, I wasn’t ready to talk about that stuff five years ago, because I hadn’t processed it and I hadn’t dealt with it. And going through the USADA hearings really opened up a lot for me. And I [am in therapy, which] really helped me realize that these things that I had been compartmentalizing, and had convinced myself didn’t hurt me, actually were hurting me. And I felt like in an effort to protect someone else’s family, I was actually hurting myself and hurting my own family.

SI: You left the Oregon Project in 2011. In the intervening years, there’s been more openness about abuse by coaches and sports staff, especially by female athletes. Did you feel like any of that impacted your decision in coming forward?

KG: Oh, definitely. I didn’t experience anything like the Larry Nassar victims did, but seeing them come forward with strength, seeing the gymnasts testify to Congress. It just feels like it’s a safer place to talk about stuff now. I’m sure there will be backlash, and there will be negativity, but I find a lot of strength in telling the truth. I’ve been really inspired by other women telling the truth. So I think we are in a different place than we were even just five years ago.

SI: When I was reading the book, I kept noticing how often isolation and loneliness came up while you were describing being on The Oregon Project team. When you look back, what role did isolation play in you not recognizing the abuse you experienced for what it was?

KG: Looking back, it’s embarrassing. All the signs were there. I felt like I was nothing without that group. Because they were my whole world. And by design, I was isolated. I didn’t room with other people on trips. At big meets, we didn’t stay where everyone else was staying. We were always off on our own. We were always by ourselves. And a lot of the time, I was the only woman on these trips. So I mean, I didn’t have a lot of confidants at that time in my life. I didn’t have a lot of friends. I knew a lot of people, especially when I was at the height of my career, but people that actually knew me—that number was small.

SI: And it was also a part of making the team seem so elite, right? That to be this boundary-pusher in the track and field world, we can’t be giving our secrets away.

KG: Totally. And I wasn’t ever one of the cool kids. I was a late bloomer, in every sense of the word. I didn’t have boyfriends growing up. I wasn’t part of the cool clique ever. And so I think that isolation made me feel like, Oh, well, this is what happens when you’re one of the cool kids. We have to be alone and people are jealous. And all those silly things. Looking back, of course, I feel like: Wow, I was so naive. So naive.

SI: At the same time, I think one of the things that people might question is that your husband, Adam Goucher, was under Alberto’s training as well. Did he ever question what was going on with Alberto and you? Or were you guys kind of in this place together?

KG: Yeah, I mean the first year, we would talk about things we saw and say, “Isn’t that weird?” But you have to remember Alberto was so powerful, and nobody else is questioning anything. And [Nike] is the biggest sportswear footwear brand, globally. And they’re trusting Alberto with our lives and our careers. So after a while you just got desensitized and you just didn’t really ask questions. [Later,] Adam did start to separate from Alberto and was having some issues with him, but at the same time I started to run really well. So he felt like he had to just sort of be there. The problem was as his relationship with Alberto started to split, I didn’t feel like I could tell him everything anymore. And then I felt like I was nothing without Alberto. I felt like: There is no Kara without Alberto. So I have to stay here.

SI: By the time you were finally recognizing the abusive patterns, was having Adam there and having been a witness to some of it a help in mustering the courage to leave?

KG: Oh, 100%. And Adam never made me feel bad. He could have said, “I’ve been telling you this for years,” or “How could you not have seen?” but he never did. When I told him I needed to leave, he was just like, “Thank God. We’re getting out of here. We’re not doing this anymore.” And then it was a slow unraveling of me opening up to him over the years. But he never made me feel bad or shameful. He was just excited that I had finally seen the light.

Jonathan Moore/Getty Images

SI: I was really shocked reading at times just how explicitly sexist and gross Alberto and Darren [Treasure, who served the Oregon Project as a “sport psychologist” was notably not actually a psychologist by training] could be and wondered how you think your gender made a difference in those situations, being the only woman a lot of the time?

KG: It was a boys’ club. And there’s things that [I did that] I’m not proud of. I went along with a lot of the jokes. I told my share of jokes, just because I wanted to fit in. And the jokes were mostly at the expense of females—it just was the dynamic and the culture. I think it really was after I had my son and my breasts were a constant conversation that I really couldn’t just go along with it anymore. I’d literally left my newborn baby to be here and to be an athlete and I’m getting jokes about my breast size and getting breast implants. What’s embarrassing for me, is how much it took before I finally started to be like: This is inappropriate.

SI: I couldn't help but think a lot about Mary Cain as I was reading and knowing the timeline of her joining the Oregon Project in 2012, not long after you left. You write about how you two finally connected just before she went public with her story of abuse under Salazar, but did you think about reaching out before that? Were you worried for her while she was there?

KG: I did. I was worried about what might happen. But in every article, she was so excited, you know, she felt like [working with Salazar] was a sign from God. And when I first talked to her, I apologized. And she said, “I wouldn’t have listened to you!” Alberto is Alberto, and he is charismatic. And when he cares, you buy it. He looks you straight in the face. He’s totally dedicated to you. And when she joined, in 2012, I hadn’t spoken to USADA yet. I certainly hadn’t spoken to SafeSport, so I’d be coming at her just trying to convince her to trust me. I always worried about her and I heard a rumor that she was unhappy there in around 2015, and I just started following her on Instagram. I thought if she ever needs to talk to someone she would be able to now DM me because I only accept DMs from people I follow. And that’s exactly what happened four years later, she sent me a DM through Instagram. I feel bad for everybody that went there after me—I just wasn’t there yet. I wasn’t strong enough yet to talk about or warn them.

SI: With your book coming out, with Lauren Fleshman’s book Good for a Girl recently released, with how we’re hearing more allegations especially from college runners about potentially abusive coaches and harmful coaching practices: Do you think we’re witnessing some kind of reckoning in the running world in general?

KG: I think there’s a lot of us that have been through similar situations throughout the years. And I think Lauren’s book does this really well, but just because we’ve done something in one way forever, doesn’t mean it’s necessarily the right way to be doing something. I didn't write this to blow up the industry and shame a bunch of people. I just feel like it could be better for the next generation.

SI: If someone reads this book who might be in a similar situation as you were, whether they’re in sports or not, what would you want them to know?

KG: They’re not alone. There’s no rulebook on when to talk about it or who to go to. It really is your own journey and your own healing process. And if you never want to talk about it, that’s fine. And if you do want to talk about it, that’s fine, too. And if it takes you a decade, like it took me to be able to talk about it, that’s O.K. There are no rules. But the biggest thing is you’re not alone, and you didn’t do anything wrong. And unfortunately, a lot of us have these stories, but they don’t have to define us for the rest of our lives.

SI: I was really moved by how you spoke with your son, Colt, about the abuse you experienced. What do you hope men and boys take from this book and your story?

KG: I hope they take away that they can be an ally. You know, this stuff is really hard to talk to kids about, but the kids know so much. When I went to go talk to Colt about [the sexual abuse], he already knew. And it’s important that we do have these conversations with our children. I want my son to grow up to be someone who sees women as equal and someone who will speak out when he sees injustice, especially towards women. When we all take responsibility for how everybody is treated, that’s when we really make change.