During a recent drive to campus, I found myself getting into a deep conversation about literature, music and philosophy with my son, an undergraduate student in the early stages of an arts degree. While we were talking, Bob Dylan’s Like a Rolling Stone came on the radio. My son — who is reasonably well informed about culture — asked who was singing.

I was surprised that he didn’t know. After silently remonstrating myself as a musicologist and his father, I tried to explain Dylan’s place and import in the history of popular music. During the conversation, I happened to mention Franz Kafka.

“Who?” my son asked again.

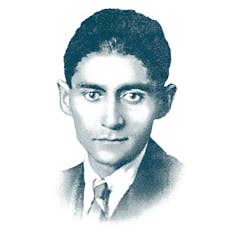

This was, for me, a devastating, gaping hole to have discovered in my son’s knowledge. From my perspective as a musicologist and scholar of Central European culture, Kafka is one of the most important creative figures of the 20th century, and his work has resonated deeply through both serious and popular culture.

Kafka even makes cameo appearances in modern pop music: his short stories and letters inspired songs by British goth band The Cure, and pop icon David Bowie references him in his classic tune Ashes to Ashes, a song that expresses Bowie’s own remorseless self-analysis and paraphrases Kafka’s pithy quote about the power of literature to “break the ice” within us.

Strange and sickly

But, really, why should we expect someone from Gen Z/Gen Alpha to necessarily know about Kafka? A strange, sickly Czech writer born in the late 19th century — 2023 marks the 140th anniversary of his birth — Kafka spent his entire life unrecognized as a literary figure of any merit.

He was perpetually unreconciled with his own writing, questioning his worth as an author — Kafka was pervasively diffident and uncertain, likely a by-product of an overbearing, disdainful and unsupportive father — and burning much of his work before he died from tuberculosis in 1924.

Though a devotee of literature, Kafka spent his life working for an insurance company, while struggling ceaselessly with self-doubt over his literary abilities. He didn’t manage to finish a single novel, publishing a relatively modest number of short stories during his brief life; Kafka’s two famous novels, The Trial and The Castle, were left incomplete and then published posthumously.

Kafka remained largely unknown outside of European literary circles until after the Second World War, with major English editions of this work not appearing until the 1950s, and relatively few new translations since. This may be due in part to what the American writer Cynthia Ozick has called “the impossibility of translating Kafka,” (though she insists at the same time that “there is also the impossibility of not translating Kafka”).

Literary giant

The rediscovery and dissemination of Kafka’s work ultimately only happened because his friend, the writer Max Brod, defied Kafka’s deathbed wishes and preserved his remaining literary work, diaries and drawings. As a result, Kafka has been and continues to be celebrated as one of the most important literary figures of the 20th century.

Kafka remains compelling to readers, but the fictional worlds and characters that Kafka created — characters who often seem to be avatars for the writer himself — also resonate beyond the borders of literary experience. Hence, the handy term “Kafkaesque,” so versatile and still readily applicable in myriad situations of absurd bureaucratic entanglements, almost a century after the author’s death.

The American scholar and literary biographer Frederick Karl once claimed that Kafkaesque has become the “representative adjective of our times…it’s the one word that tells us what we are, what we can expect, how the world works.” For Karl, Kafka’s works are shaped by “that insistence to uncover what is always uncoverable, or to recover what cannot be recovered.”

The journalist Elif Batuman wrote about the lengthy legal wranglings concerning the remainder of Kafka’s literary estate. He remarked how odd it was that Kafka’s works should be anyone’s private property. They don’t even belong to Kafka, Batuman argued, but rather “to humanity.”

Essential literary education

Reading and absorbing the uncomfortable insights of Kafka’s stories and novels is an essential part of a literary and philosophical education. The literary critic Joshua Cohen has argued that to read Kafka is to suffer along with his characters: seeking to understand Kafka is, for Cohen, “an unrequited pursuit” that is nonetheless profoundly worthwhile because, in this post-modern era, “Kafka was the last truly great writer that any of us have had.”

Reading Kafka is to find oneself in a nightmarish state of all-too-human existential angst. Take the prosaic meanderings of Josef K., the protagonist of The Trial, as unknown and unknowable authorities drag him slowly through an illogical, opaque and seemingly purposeless series of legal proceeding towards his death. Or the path of K., the main character of The Castle, as he struggles to penetrate a largely invisible and unaccountable bureaucracy to no particular end.

Such circumstances — alienation, the navigation of labyrinthine bureaucracies, being subject to the power and control of distant and sometimes arbitrary authorities — are all too poignant these days.

Read more: 'Kafkaesque' true stories of ordinary people: inside the first days of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China

Indeed, the situation that many people found themselves in during the COVID-19 pandemic could be thought of as a decidedly Kafkaesque state of disconnection. Social interaction was rigidly prescribed, information fragmented, and the directives from experts and authorities sometimes felt arbitrary.

It is not clear that this situation has really resolved itself. For this reason, perhaps more than ever, we need access to Kafka.

Kafka’s legacy

Kafka’s insistence was that literature confront us violently — that it “wound” us — with powerful truths that shatter our complacency and change us: that serve as “an axe for the frozen sea within us.” That is why Kafka’s miniature literary legacy — his two unfinished novels, less than two dozen longer stories, a few dozen short stories, letters, diaries and fragments — is so monumental, and why Kafka still matters, 140 years later.

Alexander Carpenter does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.