Climbing through the bones of a lost civilization, over the cracked tiles of now-dry fountains, and into homes carved into a mountain makes Jusant one of the year’s most meditative adventures. But there’s a feeling of excitement and danger, too, as you dangle from the end of your rope above a fall too high to even comprehend.

It can be terrifying to leave the familiar behind and embark on something new. That might be how you’d expect the developers at Don’t Nod to feel when they moved from their successful Life is Strange narrative games to the wordless mountain-climbing adventure of Jusant. But that’s not how they tell the story.

“The concept of overcoming something huge called to us.”

“Everyone was elated to do something new,” co-creative director Kevin Poupard tells Inverse. “We had to convince people that it was a good idea, so we had to convince first of all ourselves that it was a good idea.”

“The concept of overcoming something huge called to us,” he continued. “What’s interesting behind the metaphor is every person can see something different because we don’t have the same experience.”

Bringing the World to Life

Whatever people get out of Jusant’s mountain-climbing metaphor, it was essential for the game to immerse players in its fictional world. And for Don’t Nod, building this new world was an exciting chance to try something new, a departure from its previous work on choice-heavy episodes in the supernatural teen saga Life is Strange.

“Life is Strange is mostly about narrative,” says art director Edouard Caplain. “Everything was around the narrative. On this game, we wanted to focus on the gameplay.”

Jusant proceeds rock by rock, asking players to consider every handhold as they use the controller’s triggers — left then right, in rhythm — to scale the face of a mountain called the Tower that stretches into the sky.

“There was something we liked with the idea of getting out of reality,” Caplain says. “Life is Strange was very much into our lives and a very deep and complicated subject. We had an opportunity with this character climbing a tower to get out of reality and do something more dreamy and out of this world.”

“The world should speak to you.”

Building a new world doesn’t mean ignoring ours. Even if it’s a fantastical place unlike anything in the real world, Don’t Nod wanted Jusant’s Tower to feel lived in and recognizable but at the same time alien.

“We wanted to make the world not our world, but something you can relate to,” Caplain said. “The world should speak to you, so you can relate to what things are — a house is a house even if it doesn’t look like a house.”

This is easiest to see in the early stages of the game, at the lowest and once most populated parts of the Tower. In courtyards open to the mountain’s side, clusters of houses sit surrounded by the possessions of their former occupants — recognizable tables and chairs, a musical instrument that’s not quite a guitar, and endless clay pots. Low-domed buildings, some perfectly round and some like oblong seashells, fill the space. The surface of the Tower itself is full of tiny windows and intricate doors, evidence of the dwellings carved into its rock.

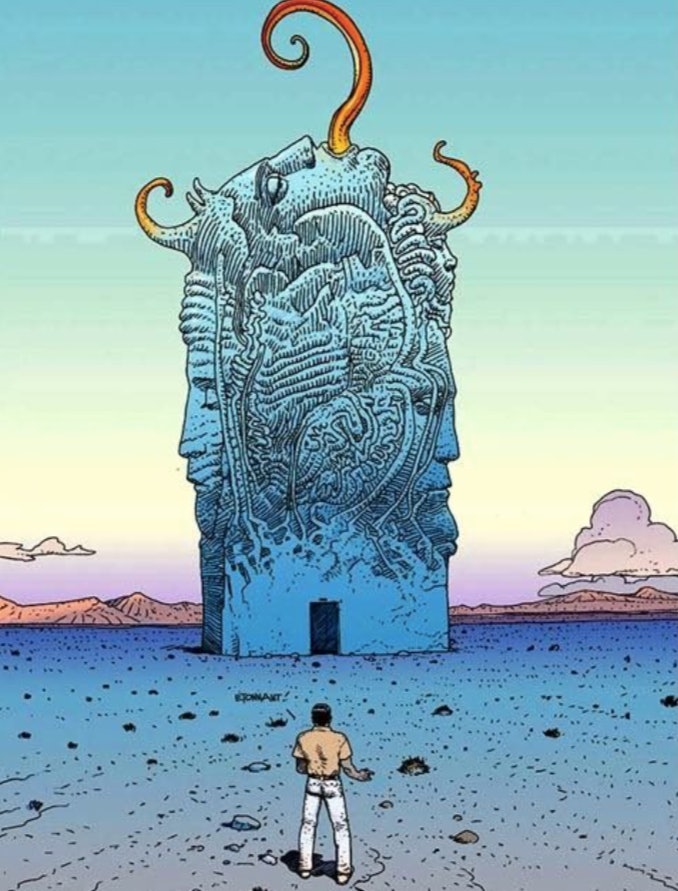

Caplain cites the work of French comic artist Moebius as an inspiration for this part of Jusant’s visual design.

“He makes a world which doesn’t exist but you can relate to it,” he said. “We tried to do something similar.”

To portray the Tower, which contains remnants of a society going through massive changes over time, Don’t Nod also researched real-world locations where the passage of time in populated areas is most evident.

“In streets in Europe, you’ve got very old buildings, and on top, there are glass roofs, so we were trying to do that,” Caplain says. “But we had another idea on top of it — that nature takes over. Moss has been growing, plants have been growing on the boats. We talked about this town Pripyat, which is next to Chernobyl, and nature has taken over the city because nobody can live there anymore.”

The idea wasn’t to mimic or even remind people of those places in the real world, but to give a sense that Jusant’s world could exist somewhere with its own history and culture. Despite its mundane influences, the Tower has a society all its own, and the environment had to convey what makes that society unique.

“When we wrote the story and the lore, we knew how many biomes we would have,” Poupard says. “Each biome has a specific atmosphere and social importance. You would have to see it as well when you’re traveling through the world.”

Finding the Flow

Designing the world was just one part of the challenge — getting it to actually run was another.

“Most of the tools we use are made for horizontality and seeing far away,” Caplain says. “When you start climbing high, everything gets much harder. Also usually in video games when you see something far away, it’s fake, and when you go there, you load into another place. In Jusant, you can see something very far and actually climb there, and when you arrive there, you can look back and see how far you traveled. It was very challenging to make it possible.”

Making your way up the Tower is hard work in Jusant, and the developers themselves had a difficult journey arriving at the game’s climbing mechanics. In one iteration, players controlled the character’s legs as well as their arms, “but that was too slow and complicated,” co-creative director Kevin Poupard says. In another, climbing was more automatic, not requiring the trigger buttons at all. (“It was too arcade.”) Eventually, the team realized it would be best to strike a middle ground between simulation and simplicity.

“Late in production we realized that climbing was not the most important thing, it was more about the flow that we wanted to provide,” Poupard says.

Climbing is just the way that Jusant gets you into that flow. Everything from how gripping handholds works to how long it takes to recharge stamina contributes to flow, Poupard says.

“You Can’t Climb Alone”

As you travel up the Tower, you move from areas with nothing more than sparse housing to places with the ruins of major settlements and evidence of how people lived their lives as fishers, farmers, or miners. Initially, the team planned to include non-playable characters who would help tell Jusant’s story, but they were eventually cut, leaving your climber the sole human occupant of the Tower.

“The characters were supposed to be witnesses,” Poupard says. “They were supposed to be here to give you hints about why the world you’re discovering is in such a bad state. We cut that out because it was impossible to do within the time frame we had.”

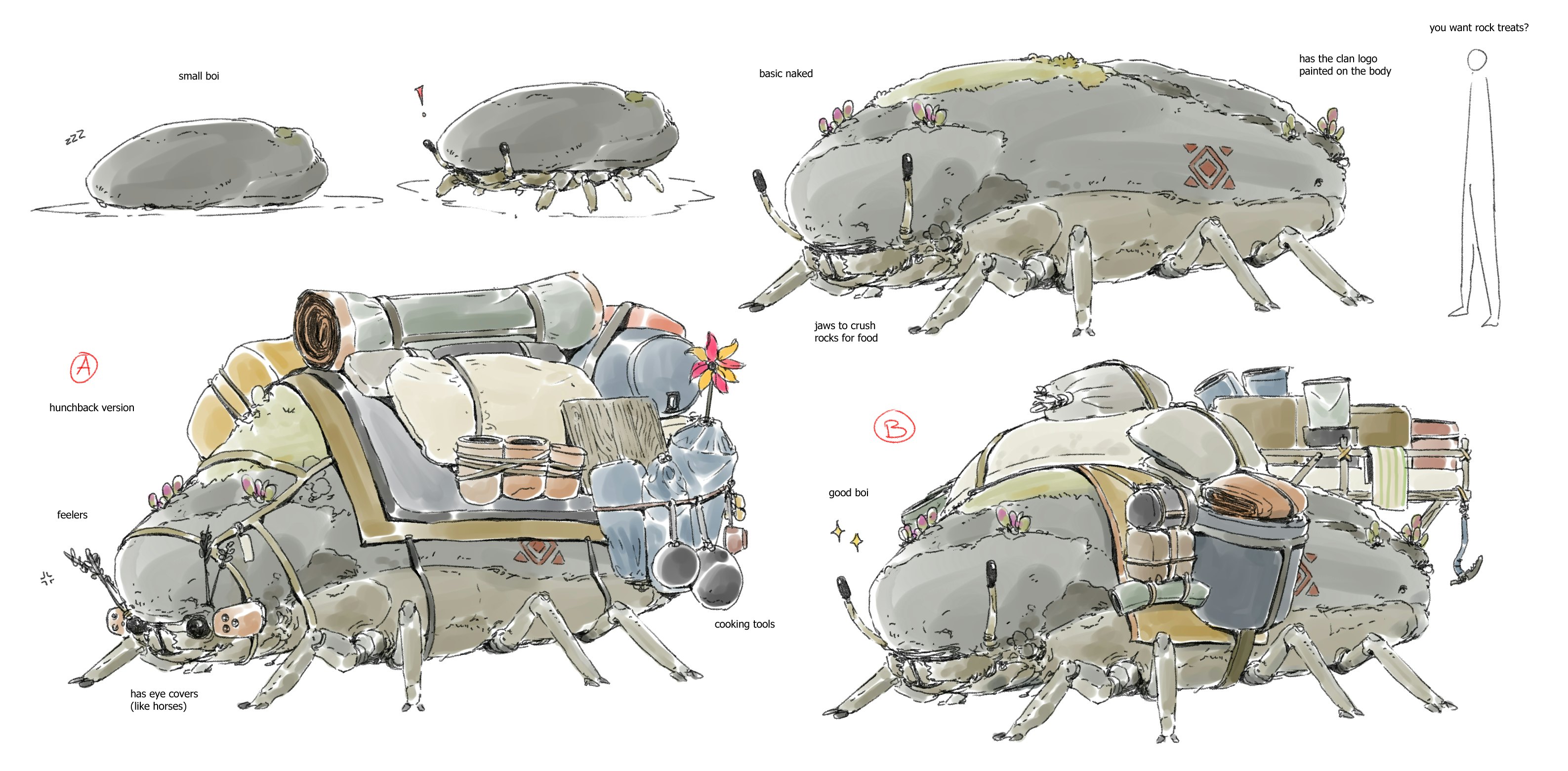

Don’t Nod was careful not to bite off more than it could chew during development. Along with cutting NPCs, developers also did away with smaller elements, like pickaxes and other climbing tools. Another, more adorable, bit of cut content was a giant, rideable insect with a rocky shell, which only appears briefly in the finished game.

Since NPCs weren’t going to fit with the size of its team and budget, the developers used the feeling of being the last person on the Tower to Jusant’s benefit. That’s when they introduced the Ballast, a tiny creature made of water that’s able to influence the environment in ways that help you on your climb. More than just a gameplay tool, the Ballast is also an essential part of Jusant’s message.

“The ballast serves a very important purpose for us,” Poupard says. “The Ballast needs the character, and the character needs the Ballast. Otherwise, none of them could make it all the way up. When we started to work on the story and the message that we wanted to deliver, it became obvious to us that you can’t climb alone.”

Removing NPCs also opened the door for another sort of character. As you climb the Tower in Jusant, you find diaries left behind by a climber named Bianca, who followed the same path as your character long ago in an attempt to bring water back to the world.

“Our narrative designer came up with the idea of creating this thread about one character where you would be the observer and you’re tracing her steps,” Poupard says. “Following someone, getting attached to someone, created something interesting narratively speaking.”

“It was a long struggle, but in the end, it’s worth it.”

While Jusant was overlooked by the Game Awards, it’s gone on to be one of 2023’s biggest cult hits. Its excellent climbing mechanics, evocative world, and incredible visual design have earned it a spot on multiple Game of the Year lists. When asked how the team felt about the game’s reception, the excitement on Caplain and Poupard’s faces gave it away before they even answered.

“It was very different from what we were doing before, so we had no idea how people would take it,” Caplain says. “It’s always a huge surprise and we’re very, very happy with the reception.”

At the end of their own climb, the developers have found their reward in the response from players.

“The team is very proud,” Poupard said. “It was a long struggle, but in the end, it’s worth it.”