The most volcanically active world in the solar system, Jupiter's moon Io, may possess a global ocean of magma underneath its surface, as well as mysteriously warm poles, a new study finds.

Io, the innermost of Jupiter's four largest moons, is slightly bigger than Earth's moon. Io is the most volcanically active body in the solar system, bursting with plumes that rise up to more than 300 miles (500 kilometers) above the surface.

Previous research found the extreme level of volcanic activity on Io is due to what is known as tidal heating. Whereas tides on Earth are caused by the gravitational pull of the moon and sun, tidal forces on Io are mostly caused by Jupiter. The resulting flexing of Io's rock creates intense heat due to friction.

The way in which volcanic activity occurs across Io likely reflects the way in which heat is flowing within the moon, shedding light on its inner mechanics. However, until now, scientists lacked a full map of Io's volcanic activity due to poor data regarding its poles, which in turn limited what researchers could deduce about the causes of Io's extraordinary volcanism.

Related: Jupiter's volcanic moon Io looks stunning in new Juno probe photos

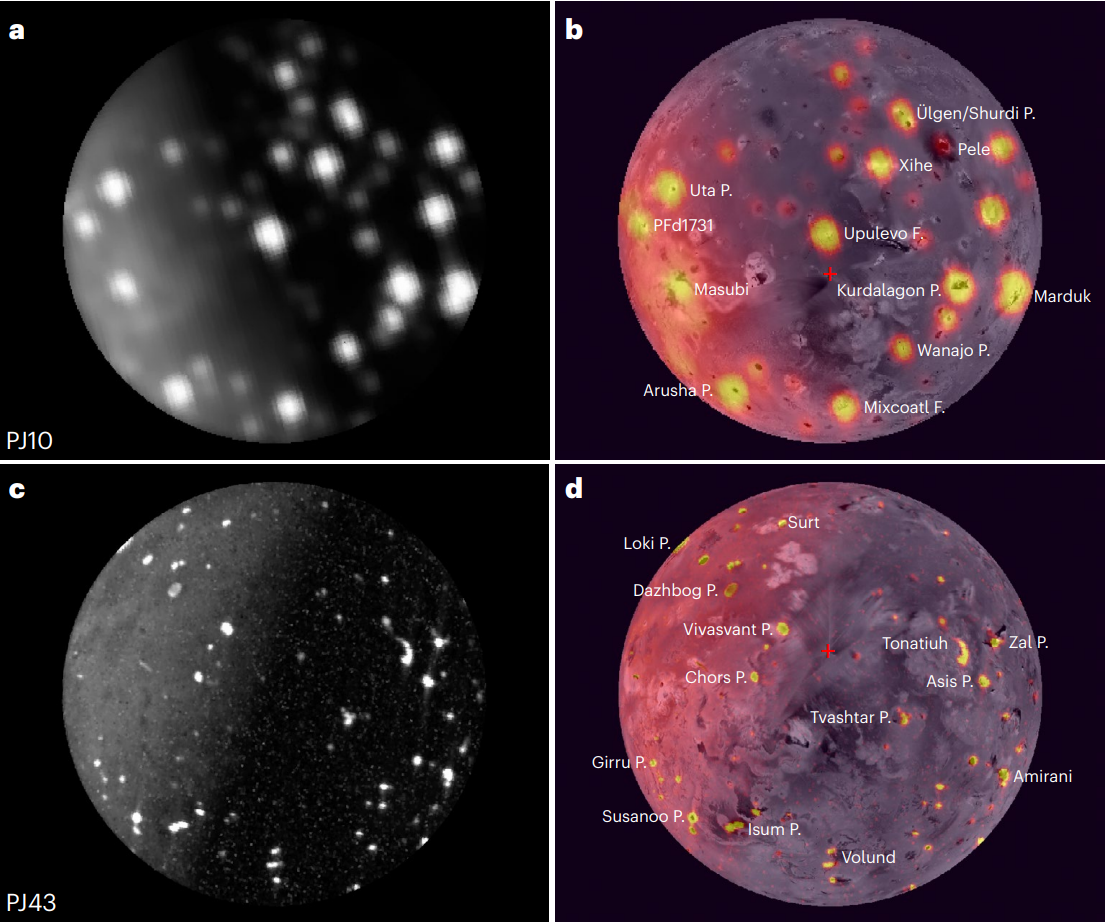

In the new study, researchers analyzed data from NASA's Juno spacecraft, which orbits Jupiter. Juno has also flown by Io, collecting near-infrared scans of its poles and enabling the first view of Io's volcanic activity as a whole.

"For the very first time, we have a global view of Io's ongoing volcanic activity, a massive leap forward in our understanding of volcanism on Io," study lead author Ashley Davies, a volcanologist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, told Space.com.

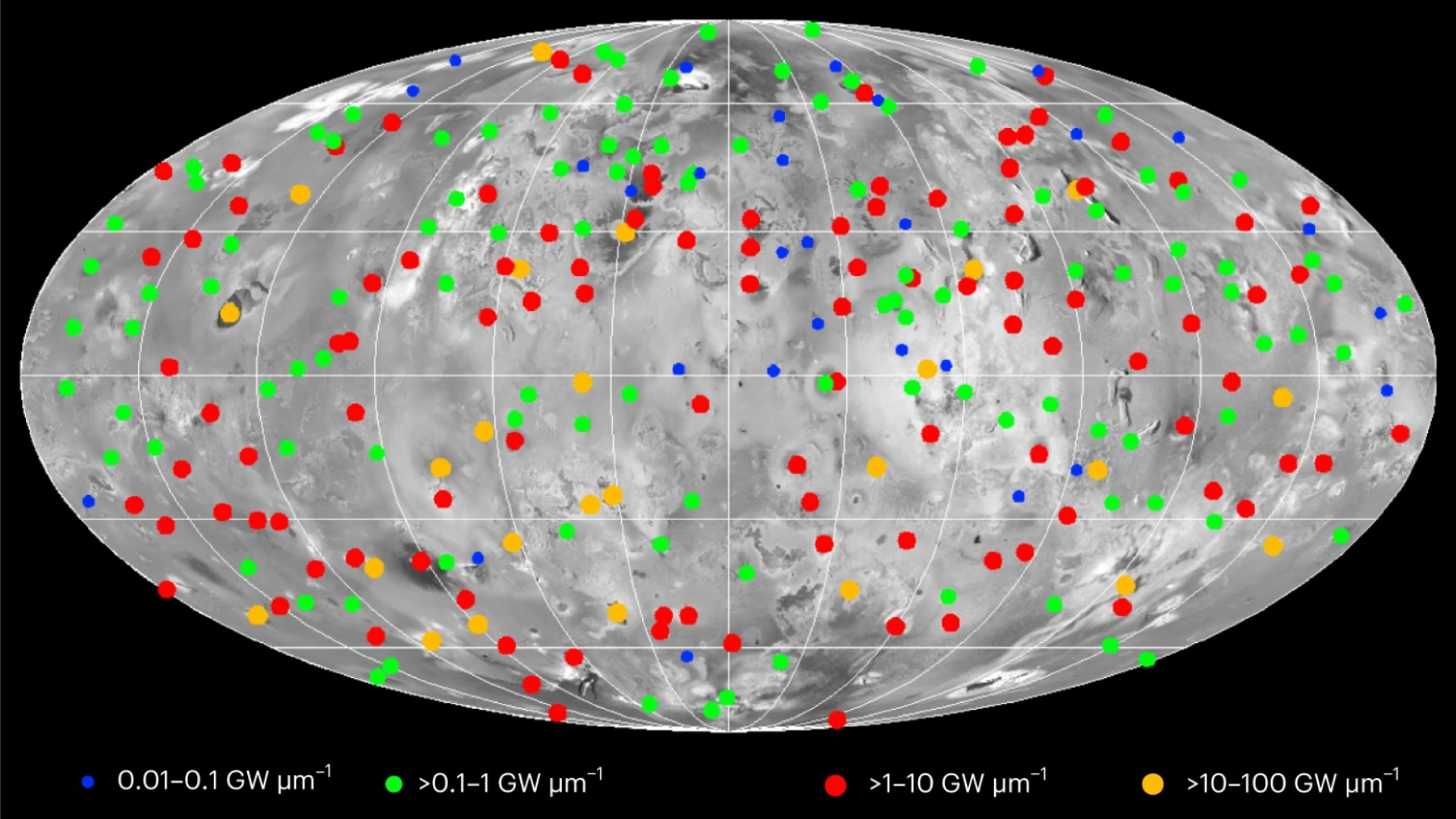

The scientists detected 266 active volcanic hotspots on Io. They found the number of volcanoes scattered across the poles is about the same as that elsewhere on Io, but the polar volcanoes emit less than half as much energy.

"Before this analysis it was thought that Io's polar volcanoes were fewer and more powerful than at lower latitudes," Davies said. "We show that polar volcanoes are about as prevalent as at lower latitudes and actually with lower emitted power, suggesting smaller eruptions."

Based on computer models of the Jovian moon, these new findings suggest that Io could have a global magma ocean under its surface. The models also suggested that the tidal heating the moon receives from Jupiter is concentrated within Io's upper mantle.

At the same time, Io's poles appeared unusually warm. This may be due to some property of Io's surface that retains heat from the sun more at the poles than elsewhere on the moon, or because there is more heat reaching the surface at the poles from deep within Io, Davies said.

The researchers also discovered that volcanoes at Io's north pole were more than twice as energetic than at the south pole. The reasons for this anomaly remain uncertain, but "possibly the south polar crust is thicker than that of the north, making it harder for magma to rise to the surface and erupt," Davies said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Nov. 13 in the journal Nature Astronomy.