In the wake of Hawaii's tragic wildfires, responsible for the deaths of more than 90 people and counting, NASA experts gathered Monday (Aug. 14) to discuss the state of our planet's climate emergency. The discussion was quite jarring.

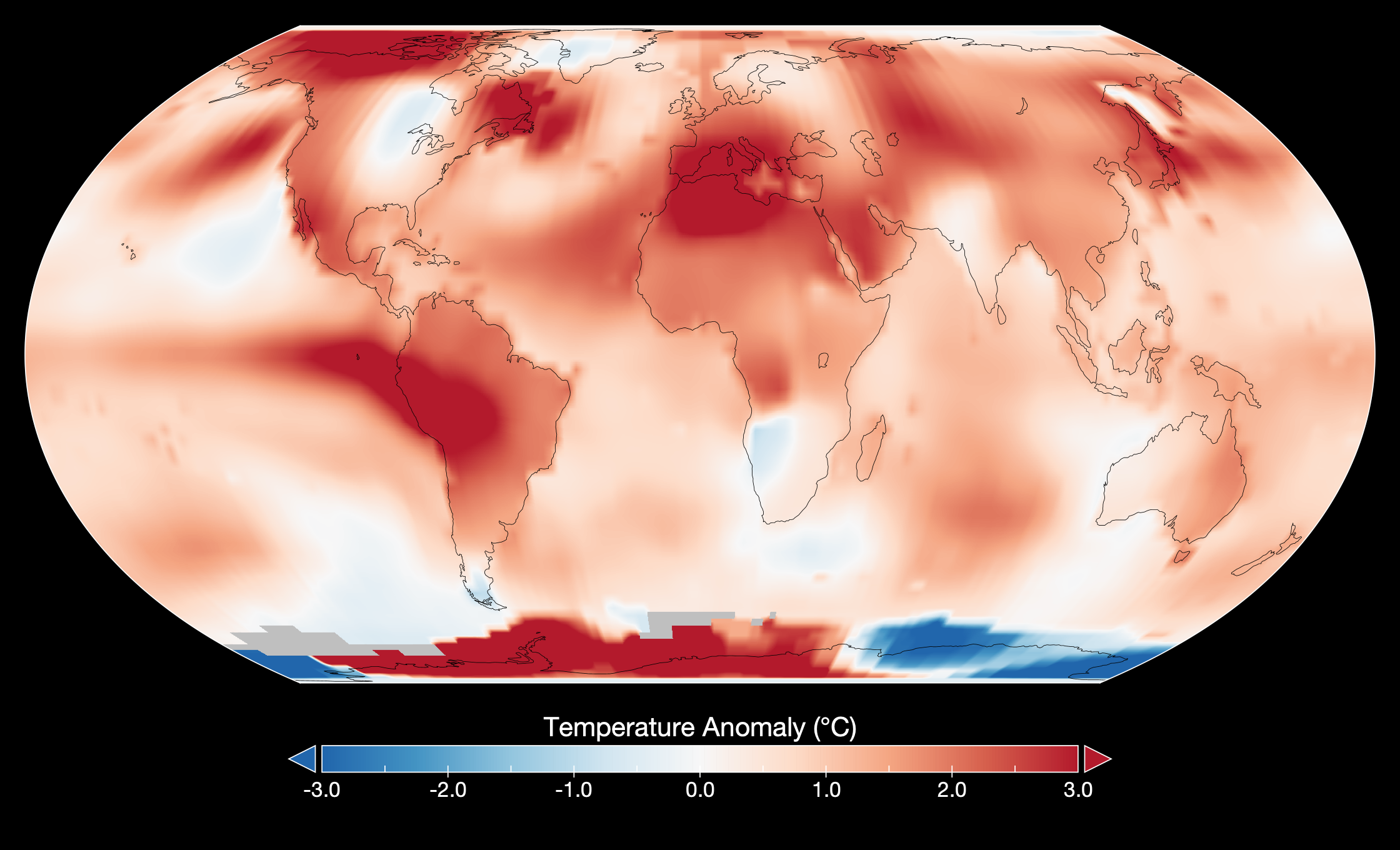

Not only did the panelists confirm that July of this year was the hottest month on a record dating back to the late 1800s, but also that the last five hottest Julys in this database occurred within the past five years. The agency further projects that next year will be hotter still.

More specifically, a statement put out soon after the conference states that July was 0.43 degrees Fahrenheit (0.24 degrees Celsius) warmer than any other July in NASA’s record, which goes back to 1880, and 2.1 degrees Fahrenheit (1.18 degrees Celsius) warmer than the average July temperature between 1951 and 1980.

"It was the warmest July by a longshot," Sarah Kapnick, chief scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said during the conference.

And a major takeaway from today's conversation was that it's humankind who holds the reins to this unfortunate truth.

"Long-term trends we've been seeing since the 19th century, particularly since the 1970s, are all due to anthropogenic effects," said Gavin Schmidt, director of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies.

The term "anthropogenic" in this case simply refers to human-driven activity such as burning coal for power, cutting down trees to build infrastructure and fostering air pollution.

Related: NASA searches for climate solutions as global temperatures reach record highs

Schmidt explained that NASA's data clearly shows other climate change factors such as El Niño events, which are natural weather patterns that lead to warming ocean surfaces, and volcanic activity create "very, very small" impacts on global warming when compared to these anthropogenic components.

El Niño, for instance, can lead to a temporary temperature increase of about 0.1 degrees Celsius, according to agency data, yet global warming observed so far exceeds that quantity by quite a bit. "Without those human contributions to the drivers of climate change, we would not be seeing anything like the temperatures that we're seeing right now," Schmidt said.

The team's long-term observations come from statistical models filled with information about Earth's temperature evolution as it correlates with different processes occurring across the globe, natural as well as not.

"Temperatures we are now experiencing, you can only get those temperatures if you include those greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere and the land-use change that we have created on Earth," Kapnick said.

Such rising temperatures are worth worrying about because they help create the perfect conditions for severe natural disasters such as drought, cyclones and wildfires including Hawaii's crisis that's been taking place over the past few days.

"Just look around you and you'll see what's happened," NASA administrator Bill Nelson said during the conference. "We have record flooding in Vermont. We have record heat in Phoenix and in Miami. We have major parts of the country that have been blanketed by wildfire smoke and, of course, what we are watching in real-time is the disaster that has occurred in Hawaii with wildfires."

On that note, while he admits there are local situations on the Hawaiian island of Maui that contribute to the risk of wildfires, such as abandoned sugar plantations and non-native grasses, Schmidt explained that global warming definitely plays a part. To name just one example, climate change has forced storms to move north, leading to less rainfall over the island and creating drier conditions.

"In general," Schmidt said, "climate change is a kind of threat-multiplier for wildfires."

Going forward, NASA intends to better understand exactly how much climate change is contributing to these Hawaiian wildfires as a specific, primary cause is yet to be formally announced.

Monday's discussion also touched upon the effects climate change is having on marine health. "The oceans are experiencing about 90% of global warming," Carlos Del Castillo, Ocean Ecology Laboratory chief at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, said during the conference. "As the oceans heat, the water expands. When you combine that with the melting of ice overland, that contributes to increases in sea level rise."

Consequences of such sea level rise — which is accelerating as the years go by — include coastal flooding and even coastal erosion. Castillo pointed to the example of Florida's Miami Beach. "They have been experiencing more frequent coastal flooding," he said, "five times more than what they experienced 50 years ago."

Castillo also brought attention to the fact that Louisiana's marshes are disappearing, and emphasized why we should be alarmed that coral reefs and sea grasses are dying off.

"Unfortunately, coral reefs cannot grow legs and move away. So they have to stay put and experience the brunt of global warming," he said. "25% of marine species have something to do with corals. They contribute to medicine. They contribute to the livelihoods of millions of people. They protect the coastline from tidal surges and storms."

Shining a glimmer of hope on the situation is NASA's upcoming PACE mission, which stands for Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, Ocean Ecosystem.

One of many climate solutions the agency is working on – in addition to self-flying aircraft that'll tend to wildfires and open-source Earth data websites for scientists to glean information from — PACE is slated to launch in 2024 and intended to detect changes in things like ocean color changes.

"A year like this gives us a glimpse at how rising temperatures and heavier rains can impact our society and stress critical infrastructure over the next decade," Kapnick said. "These years will be cool by comparison, by the middle of the century, if we continue to warm our planet."