In August 2022, Sir David Richards and Lord Lloyd-Jones were respectively appointed and reappointed as justices to the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom. With the recent retirements of Lady Jill Black, Lady Mary Arden and Lady Brenda Hale, the highest court in the land has once again returned to having only one female judge.

Observers over the past decade have noted certain improvements being made towards judicial diversity in the UK. Black was named as supreme court justice in 2017, Arden in 2018, and more recently, Lady Rose, in April 2021. Hale, who became the first woman to ever sit on the court in 2009, broke further ground when she was elevated to the role of president in 2018.

When the current president, Lord Reed, took over from Hale during the first year of the pandemic in 2020, he said that the lack of diversity among judges, in terms of both gender and ethnicity, could not “be allowed to become shameful if it persists”. Despite this laudable stance, it is undeniable that in 2022, the diversity of the court has indeed declined.

Both Lloyd Jones and Richards are, of course, of outstanding repute. But among the 12 justices who comprise the supreme court, there are now three times more white, Cambridge-educated men, with the forename David, than there are women. In response, the court itself has stated that “there is no simple solution”.

For as long as the justice system is reliant on retaining only those who can afford to progress within the legal profession, existing barriers to change will persist. Without systematic reform, such as introducing diversity quotas, the situation is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future.

UK trails comparable countries

The latest statistics show that, as of April 2022, women represent 35% of all court judges and 52% of all tribunal judges, which is respectively 11 and 9 percentage points higher than in 2014. Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) representation constitutes 10% of all judges (3 percentage points higher than 2014).

However, within senior judicial positions, at the high court and above, there remains few women (30%) and even fewer BAME members (5%). While more women, and to a lesser degree, more people of colour, are becoming district and tribunal judges, at senior levels change has been slow to non-existent.

The UK follows what experts term a common law legal tradition. Within common law jurisdictions, judge-made decisions (otherwise known as judicial precedent) represent a primary source of law. Consequently, the diversity of those sitting in that jurisdiction’s supreme court becomes all the more important.

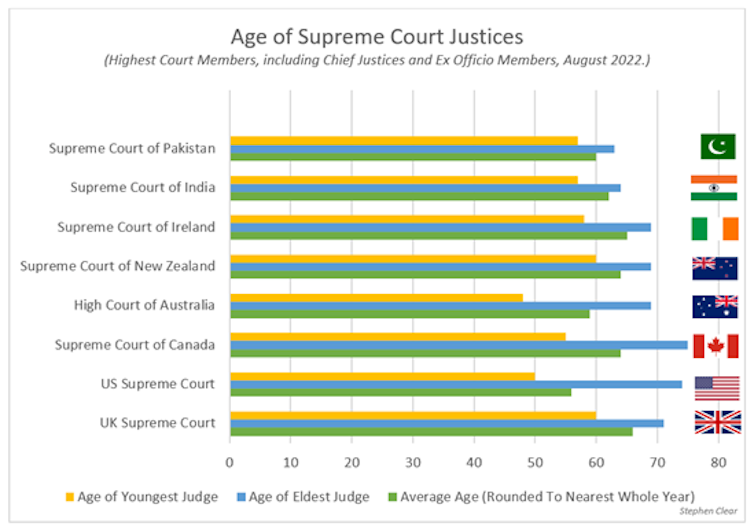

A reasonable health check of the UK’s supreme court is to compare it to the highest court of other countries following common law traditions, namely the Supreme Court of the United States, the Supreme Court of Canada, the High Court of Australia, the Supreme Court of New Zealand, the Supreme Court of Ireland, the Supreme Court of India, and the Supreme Court of Pakistan. Look through the biographies of judges on these countries’ highest courts and it becomes quickly apparent that the UK’s are the eldest, with an average age of 66.

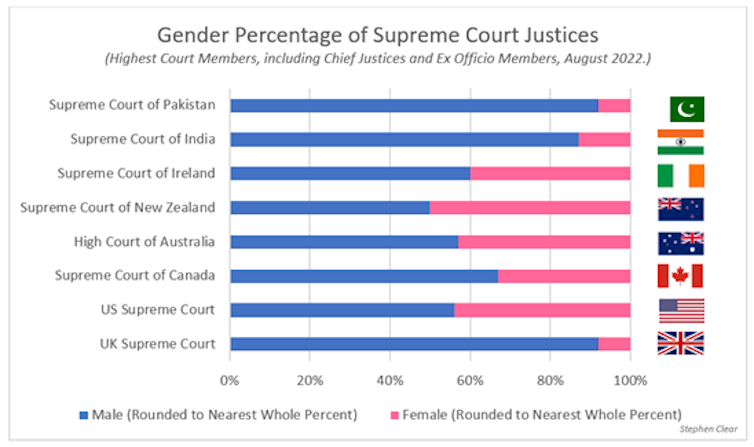

In terms of gender, the situation is even starker. At 8%, the UK now has the joint worst representation of female justices, tied only with Pakistan. This is following the appointment of the first ever female judge, Ayesha A Malik, to the Supreme Court in Islamabad, in January 2022. By comparison, we note female representation at 50% in New Zealand, 44% in the US, and 43% in Australia.

When it comes to ethnicity, the UK has simply never had a justice of colour. The Supreme Court of Canada, meanwhile, currently has two out of nine justices of colour and the US, three out of nine.

Why diversity matters

Justice organisations, and even former Lord Chief Justices, attribute the current lack of diversity to historical socio-political failures, which will take more time to be reflected at supreme court appointment level. Nonetheless, if we accept that a key part of the rule of law is not only that justice is done, but that justice is seen to be done, it must be important for those dispensing justice to reflect society and to positively shape the development of the law.

The Judicial Appointments Commission as well as senior legal professionals have reiterated their commitment toward judicial diversity. Published in November 2020, the Judicial Diversity and Inclusion Strategy 2020–2025, in particular, recognised that public confidence in, and the legitimacy of, the judiciary are sustained by judges who reflect the people they serve. If the judiciary does not draw from the widest pool and background, it will also, inevitably, miss out on talented individuals.

As the 2020-2025 strategy attests to, for judicial diversity to improve, the diversity of those professions feeding into the judiciary needs addressing. Under the current system, the majority of judicial offices are filled by barristers. Those previously practising at the Bar make up 69% of lower court appointments and 95% at senior levels.

Yet, in August 2022, criminal-law barristers voted in favour of an indefinite strike over legal aid cuts. This followed reports that their income has fallen by nearly 30% over the past 20 years, to an average £12,200 in the first three years of practice. These specialists are often paid less than the minimum wage for court hearings, or even not paid at all when hearings are cancelled.

In other words, the criminal justice system is reliant on barristers’ goodwill that often leaves them out of pocket. For those who cannot afford to do so, there are few options other than to leave the profession. And since 2016, 22% of junior criminal barristers have done just that.

Set in this context, the criminal law bar strikes become about much more than just pay. It is about diversity, equality of opportunity for progression and the wider health of the justice system of England and Wales.

Stephen Clear ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.