The pressure is on Brandon Johnson to deliver Monday in his first speech as Chicago’s 57th mayor.

But inaugural addresses are far better remembered for the mistakes mayors make than the soaring rhetoric they use.

Consider Lori Lightfoot and Harold Washington, who each made the same mistake in their inaugural addresses — for different reasons, but with similarly negative consequences.

Both challenged a City Council whose support they needed to govern Chicago and confront the city’s intransigent problems of crime, education, finance, transportation, housing and entrenched poverty.

“Business as usual will not be accepted by the people of this city. Business as usual will not be accepted by any part of this city. Business as usual will not be accepted by this chief executive of this great city,” Chicago’s first African American mayor told the crowd in the Navy Pier ballroom in 1983.

Result: ‘Council Wars’

Then-Ald. Edward R. Vrdolyak would subsequently point to that remark as touching off the power struggle known as “Council Wars.” It inspired him to organize a group of 29 Council members, mostly white, who banded together to thwart Washington’s every move.

The opposition group, which included now-indicted and retiring Ald. Edward Burke, was even more threatened by Washington’s inauguration day portrait of the dire state of city finances at that time.

The newly-elected mayor claimed he was inheriting a combined, $400 million deficit at the CTA and Chicago Public Schools and a $150 million shortfall in the city’s corporate fund — a shortfall caused, in part, by hundreds of new city jobs and hundreds of other jobs reassigned in the waning days of the outgoing administration of his predecessor, Jane Byrne.

“I will issue an order to freeze all city hiring and raises in order to reduce the city expenses by millions of dollars. We will have no choice but to release several hundred new city employees who were added because of political consideration,” Washington said on that day.

No wonder Vrdolyak and Burke felt threatened. As Byrne’s most powerful City Council allies, the employees they sponsored were among those most threatened.

Fast forward to 2019, when Lightfoot delivered her one and only inaugural address.

A former federal prosecutor, Lightfoot owed her election to the sweeping federal corruption investigation still swirling around Burke in 2019. She was literally languishing in the single digits until federal investigators raided the City Hall suite Burke occupied as powerful chairman of the Council’s Finance Committee, covering the glass doors with brown butcher paper.

Lightfoot denounced the Council as corrupt, then turned around and shamed the 50 alderpersons seated behind her into joining the cheering Wintrust Arena crowd in a standing ovation for reform. After that, she rushed back to City Hall to sign an executive order stripping Council members of their unbridled control over licensing and permitting in their wards.

Lightfoot: Starting on the wrong foot

All that set the stage for a contentious relationship between Lightfoot and the Council from which Lightfoot would never recover.

“I felt as if I was a child being scolded by a parent. … That was a major mistake for an executive who has to work with a legislative body,” Ald. Pat Dowell (3rd), Lightfoot’s hand-picked Budget Committee chair, told the Sun-Times the day she abandoned Lightfoot to endorse Johnson.

Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle, Lightfoot’s vanquished 2019 runoff opponent, was onstage at Wintrust when the new mayor “turned around and castigated the members of the body and I thought to myself, ‘Ooooh. This is not a good beginning.”

What can Johnson learn from Lightfoot’s mistake?

“If I were him, I’d turn around and say, ‘Look, I know I can’t get anything done without you. I want to work with you,’” Preckwinkle said.

“I look forward to working with Mayor-elect Johnson around the two crises that the city faces. That’s the violence and the challenge of addressing the needs of the asylum-seekers who are coming to our city and our county. For the last 12 years, I haven’t really had a partner across the building and I look forward to working with him.”

Former Cook County Assessor Jim Houlihan is in a unique position to compare both mistakes, having served as North Side liaison for Washington’s campaign and as intergovernmental affairs director in the Washington administration.

He believes Washington deliberately provoked Council Wars to “buy time” to accomplish what he knew he couldn’t because of the entrenched bureaucratic opposition.

“He knew what he was up against. The entire system of government was set against him and he knew he needed time to change that,” Houlihan said.

“He did it on purpose. He wanted them to be against him. … But it was a mistake. It hurt the city.”

It also led to “years of stories” describing Chicago as “Beirut on the lake,” he added, “and the intense racism that was generated from that.”

Houlihan believes Lightfoot’s mistake was unintentional, driven by hubris.

She was “too impressed with her election results and thinking that, by fiat, she could talk about the way things should be as opposed to the way things are. Add that to a certain amount of, shall we call it, prosecutorial arrogance?” Houlihan said.

“Being married to a prosecutor [Ann Tighe], I’ve spent many hours talking about, ‘Who died and made them God?’”

Johnson’s task: Avoid mistakes

The challenge for Johnson is not only to avoid the mistakes made by Washington and Lightfoot, but also to make the rhetorical transition from what Houlihan calls “an outsider who talks rather glibly about what should be” to “what he can do” as Chicago’s most powerful elected official.

“He needs to know that, we need taxes. How can I talk about taxes in a way that I can get it done, rather than just say, `You should do this. You should do that’ to the City Council. ... He’s got to figure out on policing, what do we do in trying to restore some confidence and some respect from people to the police and some morale issues that police, have feeling that they’re on an island by themselves,” Houlihan said.

Johnson is a talented communicator, Houlihan said, but that alone will no longer cut it — not even in an inaugural address.

“He can’t get into these lofty cliches or bon mots that are sort of shallow. He’s got to talk deeply about what he thinks he can do. He’s got to talk about it in a way that is real. Not just pie in the sky or slogans. He needs to talk about what he wants to get done and how to get it done and speak in those terms. Not about the wonderful world that can be, but about the real world as it is,” the former assessor said.

“The opportunity is that the city needs and is yearning for some leadership and is yearning for, much as the change from Trump to Biden, some decency and some willingness to address our problems in an honest fashion.”

Political strategist Delmarie Cobb has heard the media complaints that Johnson “hasn’t talked real substance yet” and needs to “put meat on the bone.”

She expects his inaugural address to “outline an aspirational road map for how he’s going to address the issues he’s facing and how he intends to govern.”

But “I can’t imagine it will go into detail because this will be his real last day to relish having won and all the positives of winning,” she added.

“Once he has the open house on Monday, it’s hit the ground running and there’s no looking back. He goes right into the summer and what that means for Chicago and violence. He has to pick a [police] superintendent. He’s hit with myriad issues immediately that are enormous issues. And, of course, the immigrant crisis.”

Chicago Teachers Union President Stacy Davis Gates has no doubt Johnson will rise to the formidable challenge.

“I depend on him to deliver the most powerful address that we’ve heard” in the last 100 years “of any mayor in this city. When you have the Michael Jordan of politics, I think he can get there,” Davis Gates said.

“You’ve seen it happen. He went from 2% [in the polls] to the 5th floor [of City Hall]. … That is a remarkable journey — even more from someone who comes from the progressive wing of our party. … You can’t get any more Jordan-esque than that,” she added.

“The mayor-elect has raised the bar. He continues to out-perform, out-maneuver, out-strategize any of the political traditions that we’ve held in Chicago. And I don’t expect this inaugural address to depart from that.”

Different mayors, same issues

Veteran communications strategist Marilyn Katz also worked for Harold Washington.

After reviewing the first inaugural addresses delivered by every Chicago mayor since Richard J. Daley in 1955, Katz said what struck her most was the “similarity of the speeches” and “persistence of schools and taxes” as the “major issues” cited.

“Kinda depressing, if you think too much about that,” Katz wrote in an email to the Sun-Times.

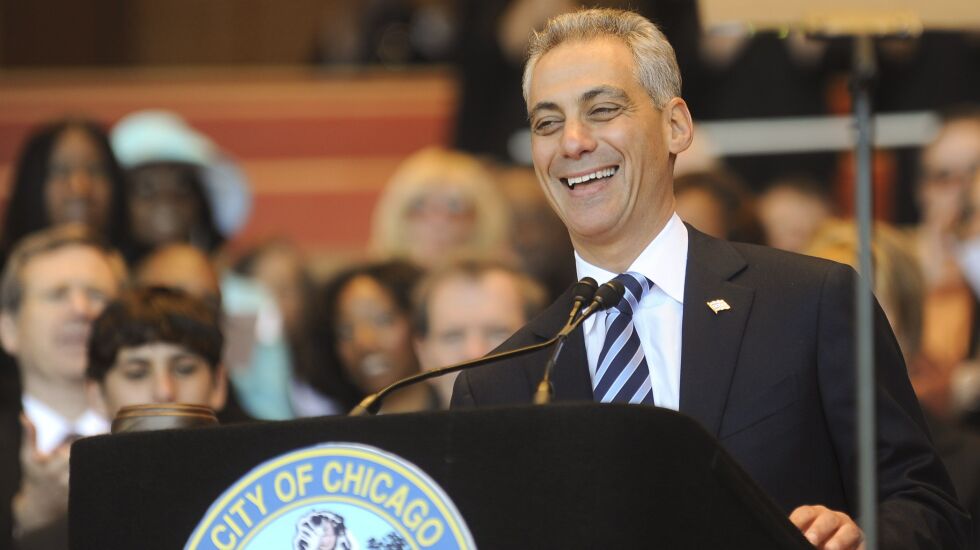

Rahm Emanuel devoted 13 paragraphs of his first inaugural address to the need to improve Chicago schools. And that was after convincing the Illinois General Assembly to lengthen the school day and school year before he had even taken office.

The die was cast for the 2012 teachers strike that was Chicago’s first in 25 years and for the record fifty school closings the following year.

“I fully understand there will be those who oppose our efforts to reform our schools, to cut costs and to make government more effective,” Emanuel said, demanding “shared sacrifice” at every level.

“Some are sure to say, ‘This is the way we do things — we can’t try something new. Those are the rules — we can’t change them.’ ... So when I ask for new policies, I guarantee, the one answer I will not tolerate is: ‘We’ve never done it that way before.’ Chicago is the city of ‘yes we can,’ not ‘no we can’t.’”

.png?w=600)