John McEnroe has carved out a second career with self-deprecating appearances playing himself on “30 Rock” and “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” not to mention a number of Adam Sandler movies, an inexplicable turn as the narrator of “Never Have I Ever” and a steady stream of commercials. He’s in that Charles Barkley/Terry Bradshaw/Shaquille O’Neal zone of ubiquitous former athletes who maintain a high level of celebrity. Some of their younger fans might not even know how great these guys were back in the day.

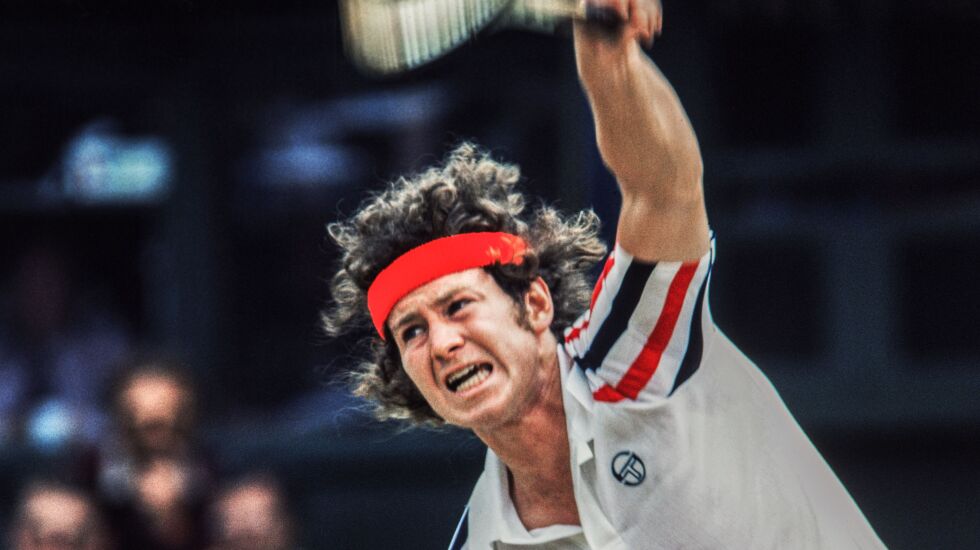

In the autobiographical documentary “McEnroe,” available on demand now before premiering on Showtime on Sunday, we’re reminded of McEnroe’s dominance on the court — as well as the antics that earned him a reputation as a brat who polarized the tennis world. Bellowing “YOU CANNOT BE SERIOUS” at umpires, partying at Studio 54, playing guitar with Keith Richards and Chrissie Hynde, involved in a tumultuous marriage to actress Tatum O’Neal and infuriating the old guard with his rebellious antics, McEnroe was one of the most famous athletes in the world in the 1980s — and all those distractions aside, he became one of the most dominant figures in the history of tennis.

McEnroe won seven Grand Slam singles titles and nine Grand Slam doubles titles and had 77 singles titles on the ATP tour. In 1984, McEnroe was 82-3 in singles matches — still one of the highest win rate seasons in tennis history. He was one of the greats.

The somewhat melodramatic conceit of “McEnroe” has its 63-year-old subject walking the streets of his hometown of New York, reflecting on his life and times. (The separate interviews with McEnroe; his adult children; his wife, the musician Patty Smyth; his brother Patrick; the legendary Billie Jean King, and Bjorn Borg tell us writer-director Barney Douglas did his homework and invested considerable talent and effort into the project.)

The first half of the documentary chronicles McEnroe’s meteoric rise in the tennis ranks during the “rock star” era of the 1970s and 1980s, in which the likes of Jimmy Connors, Vitas Gerulaitis, Ivan Lendl, McEnroe, Borg, Chris Evert, Martina Navratilova and Steffi Graff became superstars and the popularity of the sport soared worldwide. With his father, John (who became his manager), driving him relentlessly, the scrappy kid from Queens with the long hair and the trademark headband felt he had little choice but to be the best.

“If you like being around perfectionists, this was the perfect family to be around,” says McEnroe with a rueful laugh. “When I was 12 … my dad was all over me [yelling], ‘YOU CAN BE THE BEST IN THE 12 AND UNDERS!’ I’m like ‘Dad, listen, let’s take it easy.’ ”

Spoiler alert: Dad and son never took it easy, and at the age of 20, McEnroe defeated his friend Gerulaitis to win the U.S. Open. Yet even as McEnroe became the No. 1 player in the world and gained worldwide fame (and notoriety), something was missing. “I’m the greatest player that’s ever played, at this point,” he recalls. “Why does it not feel that amazing? It felt like I was doomed.”

McEnroe felt even more adrift when his great rival and good friend Bjorn Borg walked away from the sport at 26, saying he no longer had the fire inside. “Tennis is a very lonely sport,” says Borg in present day. “It’s always been and it’s always going to be … When you walk onto that court, it’s only you. I loved it and John loved it, and we connected.”

Much of the second half of the documentary focuses on McEnroe’s personal life. His marriage to the Oscar-winning Tatum O’Neal was plagued by infidelities on both sides and drug use. (McEnroe jokes that while some modern athletes take performance-enhancing substances, he was taking “performance-detracting” drugs.) He had a fallout with his hard-drinking, demanding father after firing him as his manager in an effort to strengthen their personal bond, and they never reconciled. McEnroe speaks candidly of his missteps, placing the blame squarely on himself for his on-court meltdowns and for his own failings as a father. “To sit here and dwell on tennis matches, it doesn’t feel like as big a deal as feeling like, ‘God, I f---ed up with my kids.’ That’s the worst feeling,” says McEnroe.

Here’s the good news. All five of McEnroe’s grown children appear in the documentary and come across as being at peace with the past and having healthy relationships with their father. Patty Smyth, who has been married to McEnroe for 25 years, says it best:

“This is the thing I’ve been thinking about, because I’ve been wanting to write a song about this. I married a bad boy who turned out to be a really good man. How about that.”