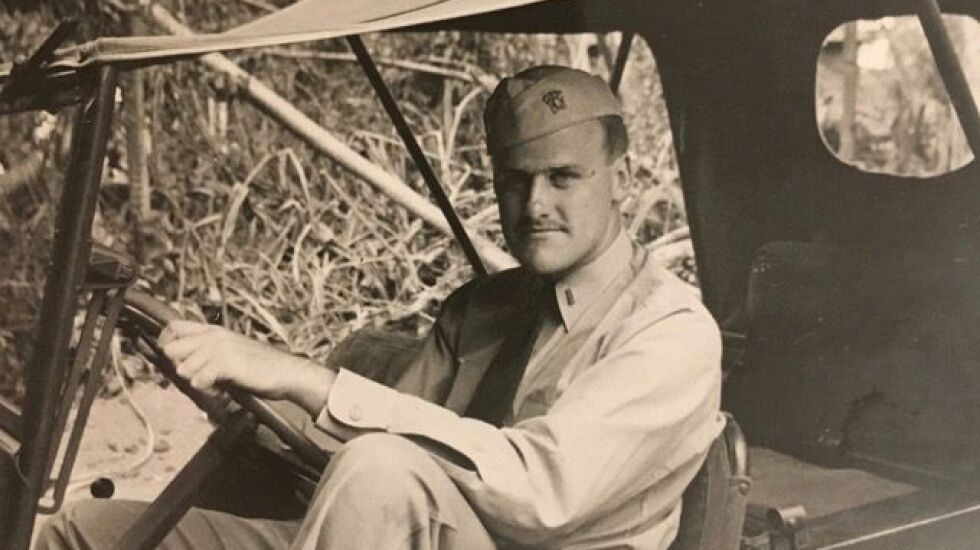

John Lawrence “Laurie” Donoghue — a South Sider at heart, if not always by geography — had a unique perspective of two of the most powerful instruments of death that the Japanese and German militaries used against Allied forces during World War II.

Mr. Donoghue, a Navy engineering officer tasked with airplane maintenance, survived multiple Japanese kamikaze attacks that claimed the lives of 79 crew members of the aircraft carrier the USS Intrepid in late 1944.

He never spoke of it until his 95th birthday, when he received a scale model of the Intrepid as a gift.

“Just before one of the attacks, the chaplain spoke and said ‘Men, we’re going into battle, and some of you will react in various ways, wet your pants, cry, but bear in mind, only about two percent of you will die in combat,’’’ recalled Mr. Donoghue, according to his son, Larry Donoghue. “And he heard a cook behind him say, ‘If that two percent is me, that’s 100 percent.’”

The first attack consisted of one plane that crashed into the side of the Intrepid. In another attack weeks later, a kamikaze crashed into the carrier’s flight deck. Mr. Donoghue, who was 25 at the time, helped a crew mate who had lost a leg to a medical station, only to see a second kamikaze, minutes later, crash into the location where he’d left the injured man.

“I think of that guy. ... I didn’t do him a favor,” Mr. Donoghue said in an interview about his war experience. “If he’d have just stayed down on the flight deck, with just losing a leg, he would have survived.”

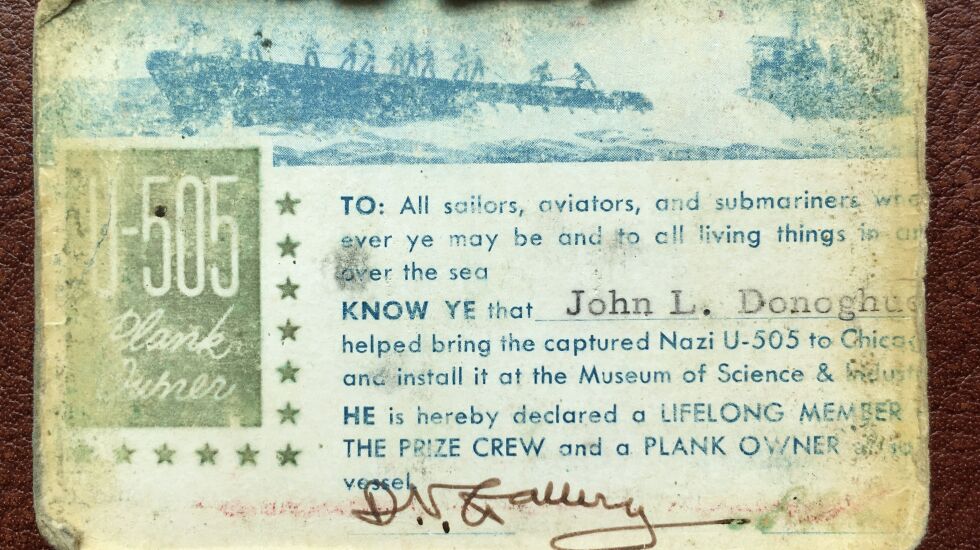

After the war, Mr. Donoghue again found himself face-to-face with another enemy war machine when in 1954, as a young engineer, he was part of a team tasked with moving a captured Nazi submarine, the U-505, from Lake Michigan to the Museum of Science and Industry without tearing up Lake Shore Drive.

The engineers used telephone poles to roll the submarine out of the water before raising it onto rails and moving it slowly a few hundred feet to its new home.

For his work as part of the engineering team, Mr. Donoghue was given a lifetime free pass to visit the U-505.

“He carried it in his wallet. He was proud of it. It was very worn,” his son said.

The submarine sat outside, exposed to the elements until 2004, when another feat of engineering moved it to its current underground exhibit space.

Coincidentally, Mr. Donoghue’s cousin, Capt. Daniel Gallery, was commander of the “hunter-killer” group of Navy ships that captured the Nazi submarine in 1944.

The USS Intrepid, too, now welcomes thousands of visitors a year. It was docked in New York City and turned into a floating museum in 1982.

Mr. Donoghue died Sept. 4 from pneumonia. He was 104.

He was born in Chicago on Feb. 23, 1919, to George T. Donoghue, a civil engineer, and Clara Roche Donoghue, a school teacher.

Mr. Donoghue grew up in Ravenswood until his father, a Chicago Park District employee, was promoted to the newly-created position of general superintendent of the Chicago Park District and moved his family to a Park District-owned house at the north end of Washington Park.

Mr. Donoghue, “a highly verbose individual,” got the nickname Buck as a teen when a classmate he carpooled with from the South Side to Loyola Academy — then located in Rogers Park — told Mr. Donoghue: “You’re just like the Buckingham Fountain, you just run on and on and on,” his son said.

Mr. Donoghue earned a civil engineering degree from the Illinois Institute of Technology in 1941 and met his future wife after the war while visiting his sister, Cecily Hansen, who’d just given birth and took it upon herself to orchestrate a meeting between her brother and a nurse, Connie Craven, who was caring for her.

They married months later at Holy Name Cathedral and settled in Evanston and later in Glenview, but Mr. Donoghue considered himself a South Sider and took his family to a White Sox game every year.

Mr. Donoghue spent 46 years with the engineering firm Ralph Burke Associates, where he worked on municipal projects, such as plans to build O’Hare International Airport, underground parking garages in Grant Park and shoreline protection measures in Evanston.

He rose to president of the company before retiring in 1992. He later opened his own firm that provided security controls to prevent the owners of parking lots from becoming victims of fraud. He retired from that business at age 96.

At 97, Mr. Donoghue, who loved traveling, went to New Orleans for Mardi Gras with his wife on a spontaneous adventure to the city where the couple had honeymooned. Mr. Donoghue was unfortunately mugged on the street, but the couple made it home safely.

Mr. Donoghue was also keen to share advice, especially with his kids and grandkids, like the importance of never being too busy to take the time to help someone in need, and making friends with people who are younger because if you live long enough you are going to outlive all your friends, and having friends is important.

He once wrote a piece called “How to Know You’re in Love” for a friend’s son who was in a romantic quandary. It suggested the lad ask himself questions like: Are you constantly thinking of nice things you can do for her? Do you enjoy activities like playing cards with her versus paid entertainment, like seeing a movie? Have you lost interest in dating others? Are you willing to change your behavior if she asks?

In addition to his wife, Connie, and his son, Larry, Mr. Donoghue is survived by his sons Gerry and Kevin, as well as his daughters Patti Cashman and Terry Donoghue, nine grandchildren and 11 great-grandchildren.

A memorial service is being planned.