Dr. John Froines long knew what his legacy would be.

“They’ll probably put it on my tombstone that I was one of the Chicago Seven,” he told the Sun-Times with a laugh in 1979.

Dr. Froines, along with six other anti-war activists, faced charges of conspiracy to incite a riot after protests outside Chicago’s 1968 Democratic National Convention devolved into chaos that put a national spotlight on police brutality, amplified criticism of the Vietnam War and highlighted a growing divide between the establishment and a burgeoning counterculture.

But for decades after his acquittal alongside the rest of the polarizing Chicago Seven, Dr. Froines made a name for himself as a renowned chemist, professor and environmental activist — and even as a federal bureaucrat.

He sometimes downplayed the significance of the courtroom drama that captivated the nation, but he acknowledged its lasting impact.

“I think it was very successful, although obviously [it] had a reputation that was probably greater than it actually accomplished, but I think the trial really did affect people’s lives, and it affected the anti-war movement,” Dr. Froines said last year on a Chicago Bar Association podcast.

Dr. Froines, 83, died Wednesday at a hospital in Santa Monica, California, according to his daughter, Rebecca Froines Stanley. He had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

A native of Oakland, California, Dr. Froines was studying at Yale University — and an active member of Students for a Democratic Society — when he met others who would be branded along with him as the Chicago Seven.

They traveled to Chicago to protest the Vietnam War outside the ‘68 convention, which erupted in angry outbursts of violence — mostly on the part of baton-wielding police officers against the anti-war demonstrators.

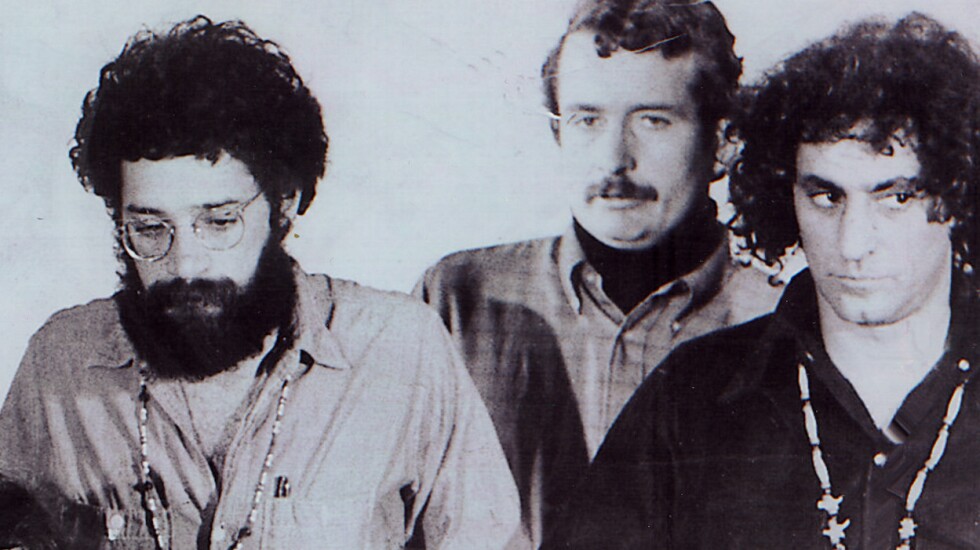

Arrested in the chaos and put on trial were Dr. Froines, Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Tom Hayden, David T. Dellinger, Rennie Davis, Lee Weiner and Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale. Combative U.S. District Judge Julius J. Hoffman eventually severed Seale from the trial, leaving the seven defendants who gave the trial its name.

Alongside the courtroom antics of Abbie Hoffman — who famously challenged Mayor Richard J. Daley to fight in jest — Dr. Froines was widely viewed as the most strait-laced of the revolutionary bunch.

He was among two acquitted of all charges. Five were convicted of crossing state lines to incite riots, but all eventually won on appeal.

Dr. Froines then hosted a series of speaking engagements with anti-war messages, and joined the Black Panther Party Defense Committee.

A chemist with degrees from the University of California, Berkeley, and Yale, he taught at the University of Oregon and the University of California, Los Angeles. He pushed for cleaner air quality by identifying toxic air contaminants, according to his bio at UCLA, where he most recently was listed as professor emeritus at the Fielding School of Public Health.

In the late 1970s, he was appointed by President Jimmy Carter as the first head of the Office of Toxic Substances in the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, but despite his bureaucratic status, he retained the fervor and activism that marked his youth.

“I haven’t changed,” he told the Sun-Times in 1979. “We’ve gone a long way toward protecting working people since I’ve been here and I don’t think that’s really so different; it still represents a social commitment.”

His family recalled that commitment in more ways than one: Froines ran marathons and took daily trips to the gym until he was 80 years old, lasting longer than his children on the treadmill, according to his daughter. And while his anti-war work might be what the general public remembers most, it’s the same dedication that translated to other parts of his life, Stanley said.

“When the movements and fanfare of the ‘60’s broke apart, he didn’t give up his work in social justice, but continued and persisted — seeking truth through rigorous science, and subsequently, justice,” Stanley wrote in an email to the Sun-Times.

Froines is survived by his wife, Andrea Hricko, his daughter, and his son Jonathan Froines. He also leaves behind two granddaughters.