When U.S. Senator John Cornyn was last up for re-election in 2014, the Texas Democratic Party was in a bad way. Just a month before the March primary, the party was warning Democrats not to support the leading Senate candidate, Kesha Rogers, a conspiratorial Lyndon LaRouche Democrat who wanted to both “crush Wall Street” and impeach Obama.

The party’s preferred pick—and eventual nominee—was David Alameel, a self-funding multimillionaire dentist and conservative Democrat who had spent $4.5 million of his own money in a crowded 2012 primary for the 33rd Congressional District in Dallas and Fort Worth, netting himself 2,000 votes and a fourth-place finish. When the 2014 Senate primary rolled around, Alameel had more luck, beating the LaRouche Democrat in a runoff, but he was very clearly not a real threat in the final race. Cornyn languidly swatted him away, getting 62 percent of the vote.

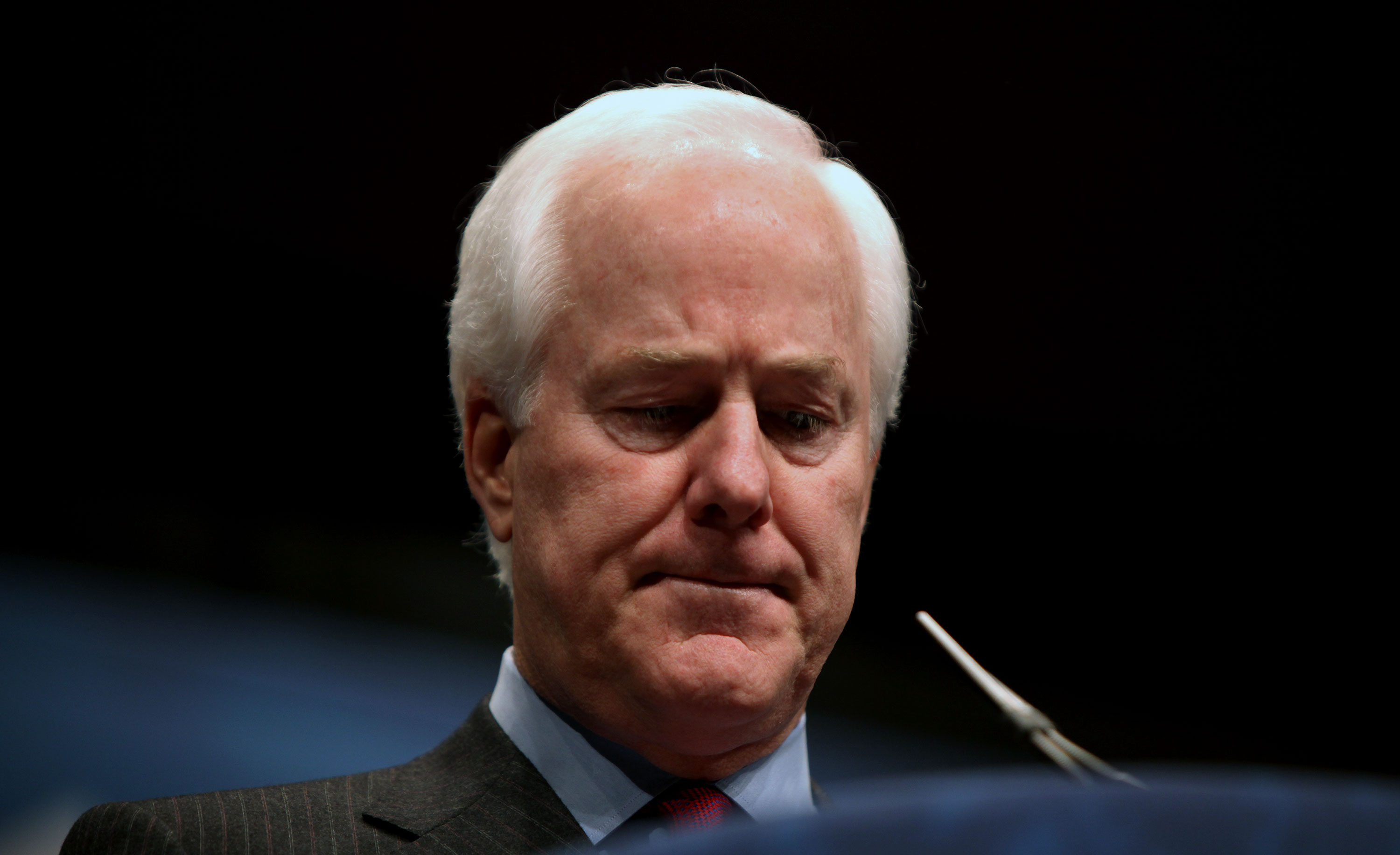

Cornyn hasn’t had much trouble holding on to the Senate seat he won after Phil Gramm left the post in 2002, but now a new clutch of Democrats is lining up to take on Cornyn in 2020. There’s Royce West, a sitting state senator from Dallas; MJ Hegar, who ran a viral campaign that helped her come close to ousting a Republican congressman in a conservative district near Austin; Chris Bell, a former congressman from Houston and the Democrats’ failed 2006 gubernatorial nominee; and Amanda Edwards, a Houston city council member.

So why all the renewed energy for a seat that Cornyn has barely had to campaign to keep?

The whiff of Republican vulnerability in Texas entered the air last year, when Beto O’Rourke ran against Ted Cruz, the state’s much-maligned junior senator, and single-handedly captured the imaginations of downtrodden Texas Democrats with an energetic campaign that got as close to the winning stake as a horseshoe ever could.

More specific to Cornyn, Democrats believe he’s uniquely vulnerable, pointing to early polling indicating that the longtime senator is surprisingly unknown and even more unpopular than Cruz. Playing up Cornyn’s closeness with Trump, the thinking goes, will further drive moderate suburban voters into the arms of Democrats.

There’s also the omnipresent fact that Texas’ demographics are rapidly shifting, which means that the electorate is becoming younger and less white. The state’s Hispanic population is on pace to outnumber the Anglo population by 2022.

While none of the candidates have really nailed down any positions, they each represent a different type of political profile. West, who is black and a centrist Democrat, is hoping that his political base in one of the bluest blocs of the state will help propel him to the front. He’s also the most experienced candidate in the race and is leaning into his record of getting things done in a state Senate dominated by conservative Republicans. Cornyn ran attack ads during the Democratic presidential debates last week casting him as a far-left liberal.

Hegar got into the race first back in April and is running a more traditional red-state Democratic campaign that emphasizes her experience as a military veteran. She’s casting herself as the middle-of-the-road fighter who can take down Cornyn. “A third of the state is not that interested in policy nuance—they want to see toughness; they want to see who’s gonna go and fight for them,” Hegar said at a campaign event this week.

And then there are three longer-shot candidates. Sema Hernandez, a Democratic socialist and Medicare for All activist, is the furthest to the left. She was the first to jump in the race after an unexpectedly strong primary performance in Texas’ 2018 Senate primary. Then there’s Chris Bell, who has been trying to reignite his political career ever since losing his Houston congressional seat in 2004. He challenged Governor Rick Perry in 2006 as a moderate Democrat, failing to crack 30 percent of the vote in a four-way race. Now, he’s apparently trying to compete for the progressive lane in the Senate primary as a supporter of Medicare for All. Amanda Edwards, an African American millennial from Houston, believes she’s the candidate who can best mobilize Democrats’ ascendant base of young and diverse voters.

That’s the same base O’Rourke’s campaign was able to energize. O’Rourke also drove up historic levels of turnout in major cities and along the border, as well as making substantial inroads in the suburbs.

While it’s not at all apparent that anyone currently in the Democratic field can rekindle the magic of Betomania (if they even intend to try), the vibrancy of the statewide Democratic primary may be an indication that the party is coming back to life.

Interestingly enough, Democrats thought the same thing in 2002, when Cornyn was first running to replace Gramm. That was also the last time there was a truly contested statewide Democratic primary. The open seat attracted a host of moderate politicians like Ron Kirk, the African American mayor of Dallas, and Ken Bentsen, a Houston congressman and the nephew of legendary Democratic Senator Lloyd Bentsen. Dan Morales, the former Democratic state attorney general, was also considering jumping in as part of a political comeback.

At the time, Democrats believed that the path back to statewide power was in the middle of the road and the primary was a race to moderation. Kirk won that race, shoring up the Democrats’ much-lauded Dream Team ticket. But Cornyn was a close ally of a popular Texan who was the president of a country at war. He easily bested Kirk by 12 percentage points.

Eighteen years later, Democrats are in a similar situation. But there are important differences now. The Democratic challenge to Cornyn was a matter of political opportunity, trying to snag a rare open seat. As the results showed, Texans had no real appetite to send a senator from the opposing party of President George W. Bush to Washington. Today, the president is a wildly divisive figure who is in the middle of his own endless war—this one waged against Democrats, immigrants, the press, and the deep state. And this time, Cornyn’s close connection to the White House is not so clearly a political asset.

Editor’s note: This post was updated to include the candidacy of Sema Hernandez. The Observer regrets the omission.

READ MORE:

-

How Beto Built His Texas-Sized Grassroots Machine: To pull off the largest GOTV effort in state history, O’Rourke turned to the top architects of Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign.

-

Dear Beto and Julián, Please Don’t Run for President: Most failed presidential campaigns are high-risk bids for personal glory and a waste of time and money.

-

Texas Republicans Fail to Kick a Million People off Food Stamps After Trying for a Year: As rural Americans struggled in 2018, Midland Congressman Mike Conaway was laser-focused on making it harder for the working poor to eat.