Virginia Woolf always maintained that, of all of the great writers, the British novelist Jane Austen “is the most difficult to catch in the act of greatness”.

To my mind, the groundbreaking Russian playwright Anton Chekhov gives Austen a close run for her money. He is also, as one tends to find when seeing his work performed live, very hard to get right.

This difficulty stems from the subtlety and nuance of Chekhov’s writing, which, on the surface, appears to trade exclusively in the trivialities and minutiae of everyday existence.

Nothing, however, could be further from the truth.

Chekhov’s genius lies precisely in his ability to achieve a great deal with seemingly very little. He conveys emotional depth and intellectual profundity through subtle, almost imperceptible, shifts in tone and characterisation, all while eschewing conventional dramatic action.

With that in mind, it is heartening to be able to report the Ensemble Theatre’s exceptional and engaging production of Uncle Vanya successfully captures the essence of Chekhov’s work.

A storied history

The history of Uncle Vanya, which was written in 1897 and first staged in 1899, is complex. Born on January 29 1860, Chekhov grew up in Taganrog, a port city in Southern Russia. He started writing in school and finished a full-length play by the age of 17.

In 1879, after moving to Moscow to study medicine, Chekhov supported his family by writing humorous sketches and stories for various journals. This work provided him with a crucial source of income.

At the same time, he continued to hone his skills as a dramatist. In 1888, he began work on what would become his third play, The Wood Demon.

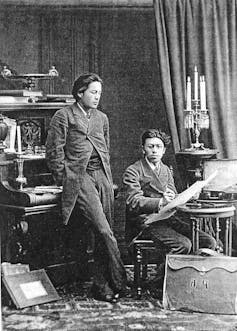

Written in collaboration with his friend and publisher, Alexi Survorin, Chekhov finished the script in October 1889. The play premiered at the Abramov Theatre in Moscow on December 27 1889. It was a resounding flop. The reviews were overwhelmingly negative and the production ground to a halt after only three performances.

Bruised but undeterred, Chekhov kept chiselling away at the play. Nearly a decade in the making, the eventual result was Uncle Vanya, which differs drastically from The Wood Demon in terms of running time, formal structure and tonal affect. While The Wood Demon unfolds across multiple venues, Uncle Vanya, a work about unrequited love and thwarted ambition, is set in a single location.

This change in setting afforded Chekhov the opportunity to intensify his focus on the internal conflicts and interpersonal dynamics of his cast of characters. They represent, as the cultural theorist Raymond Williams says, “a generation whose whole energy is consumed in the very process of becoming conscious of their own inadequacy and impotence”.

Conflicts and comedy

The plot of the tragicomic play centres on a dilapidated rural estate, where the eponymous Vanya and his niece Sonya toil to maintain the property for the benefit of Vanya’s brother-in-law, Professor Serebryakov, whose unexpected visit with his young wife, Yelena, disrupts the daily routine of the disgruntled household.

Tensions mount, passions flare and tempers threaten to boil over.

Adapted by the award-winning Australian playwright Joanna Murray-Smith and directed by Mark Kilmurry, the Ensemble Theatre’s production excels in rendering these escalating conflicts, leavened by moments of genuine comedy.

This is no mean feat. In many interpretations of Chekhov, as Murray-Smith has acknowledged, “the comedy is missing because it just doesn’t translate to now”.

By the same token, Murray-Smith expresses doubts about pandering to contemporary tastes when it comes to theatrical adaptation:

In a good production of a Chekhov, you really don’t need to make any changes if you don’t want to: you can present it in the world at the end of the 19th century […] I’m not doing very well at selling my own job here, but a lot of the time I think the modernising is completely unnecessary.

Happily, this production – which also makes excellent use of the Ensemble Theatre’s intimate theatrical setting – proves Murray-Smith correct.

The performances are all outstanding. Abbey Morgan gives us a preternaturally stoical Sonya. Chantelle Jamieson’s portrayal of Yelena blends passion and irony. Deftly shifting between satire and sincerity, the cast evokes both laughter and real sympathy from the audience.

When handled with due care and proper attention, as it is here, Chekhov’s play is simultaneously timeless and timely.

It addresses themes of ecological degradation, intergenerational strife and societal upheaval – just as relevant today as it was in 1899.

Uncle Vanya is at Ensemble Theatre, Sydney, until August 31.

Alexander Howard does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.