Joan Didion’s old things went up for auction this week, and I’d love to say I had no interest in owning them. I’d love to say I hadn’t even bothered to peek at the online catalogue for “An American Icon: Property From the Collection of Joan Didion”, the estate sale held by Stair Galleries. But, like a teenage fangirl drawn to the literary flame, I pored over the descriptions of all 224 lots. There’s God hidden among the minutiae.

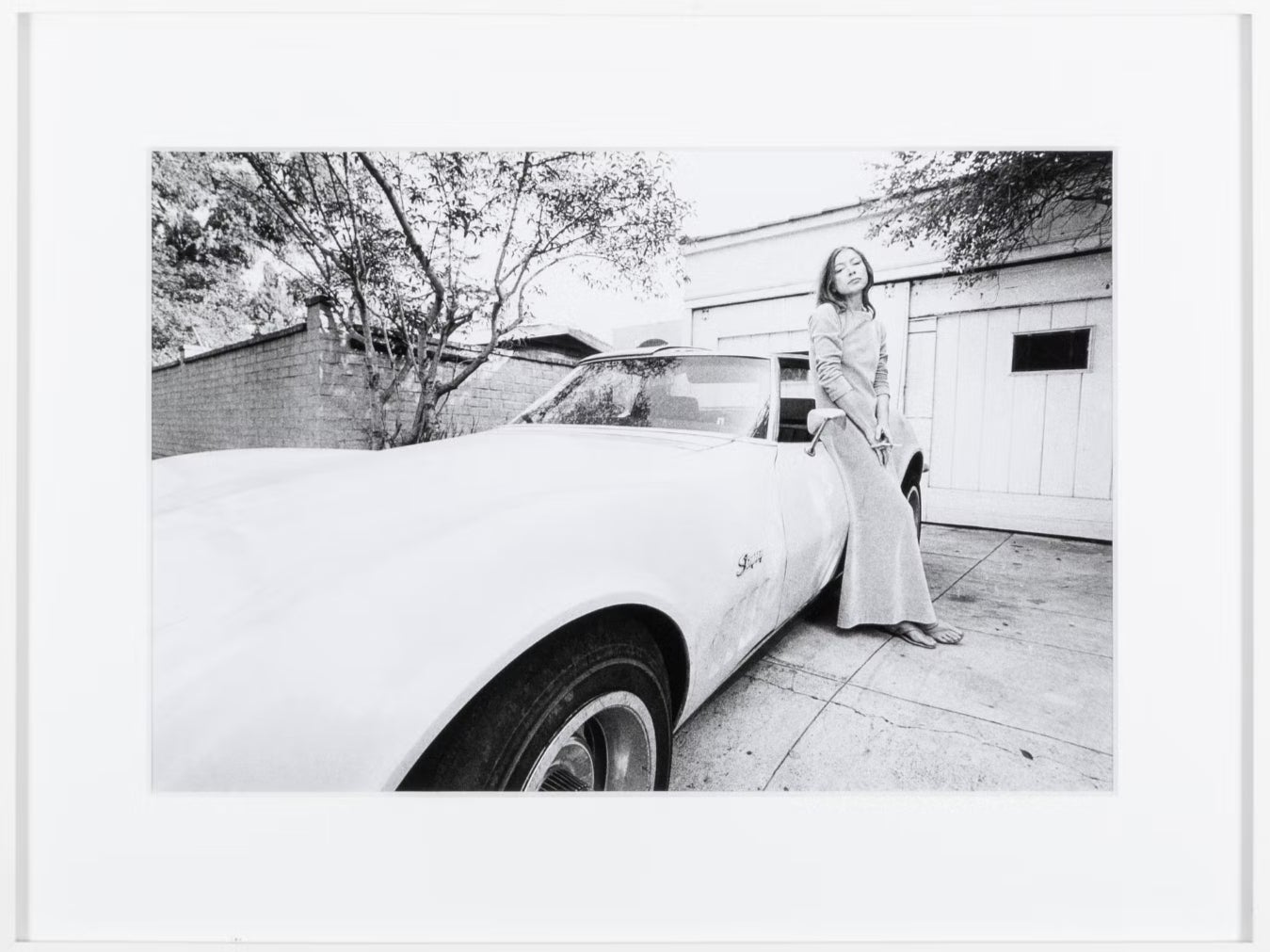

I didn’t bid on anything from Didion’s Manhattan apartment – the prices were shocking. A photo of the author in her Corvette Stingray sold for $26,000 (£22,000) on Wednesday. A pair of Celine faux tortoise shell sunnies – not even the black pair she wore in a 2015 campaign for the brand – cost their new owner $27,000.

The items, chosen by auction house specialists working with Didion’s family, aimed to showcase a side of the author less well known to her readers. At that, they succeeded. I own every book the Sacramento-native published before her death a year ago at the age of 87, but I never would have guessed that the writer who managed to knit California nonchalance with East Coast steeliness owned so many novelty kitchen aprons. My favourite read “Maybe Broccoli Doesn’t Like You Either” and came dotted with dryer lint (proof of use!).

For those in it for the long trawl, the auction images and descriptions are embedded with satisfying bits of Didion trivia. Any serious fan would recognise the mammoth writing desk for sale as the same one that featured in the 1976 Life magazine photo spread with Didion’s husband John Dunne and their daughter Quintana Roo. But did you know that her office desk was actually a badly splintered oak table?

I spent hours clicking through the catalogue with a voyeuristic dedication as embarrassing to me as it would be to the famously aloof Didion herself. I tried to fit the artefacts – from the art that decorated her walls to the tat that filled her drawers – into the idea of her I’d gleaned from her essays. The same idea reinforced by the purse-lipped portraits that can be seen today on everything from tote bags to fridge magnets. When I noticed a souvenir from Maya’s on Saint Barts in the auction, for example, I immediately opened a new window in my browser. “Permanently closed.” I flicked through old photos of the waterfront restaurant and struggled to imagine Didion, with her glossy bob and glum resting face, relishing the tropical sunset.

There were three entire auction lots devoted to unused writing paper. Tucked among the empty Moleskines was an incongruously twee notebook bound to resemble a Penguin edition of Pride and Prejudice. I say incongruous, but really how well do I know Joan Didion? Revealed in the sale of so many of her things was the fact that she stickered her books with personalised bookplates: “From the library of Joan Didion.” Would you have guessed Didion had personalised bookplates? Did she notice the pile running low sometimes and restock them?

Could you have known from Didion’s incisive prose and impeccable style that she kept her mantle dotted with seashells? Would you have guessed that during those glamorous, unfussy dinners she describes in The White Album that her guests were sitting on yellow slipper chairs adorned with colourful butterflies? It’s well-known that Patti Smith played at Quintana’s memorial service after her death in 2005, but not that a photograph taken by Smith hung in Didion’s apartment. Did she think of that sad day whenever she passed it?

Anyone who’s read Didion’s 2005 memoir The Year of Magical Thinking knows the devastating impact her husband’s sudden death had on her. Thanks to the estate sale – to benefit medical research and the Sacramento Historical Society – we now know the precise dimensions of the Pembroke table where John Dunne’s heart attack happened. But the table is the ghoulish exception in an auction mostly comprised of objects more precious than provocative – first editions, art books, the hurricane lamp collection Didion documents in Magical Thinking. “Clean sheets, stacks of clean towels, hurricane lamps for storms, enough water and food to see us through whatever geological event came our way. These fragments I have shored against my ruins, were the words that came to mind then.” Didion’s copies of TS Eliot’s poems were for sale, too.

Dig deep enough into the catalogue and there are little mysteries to be solved. For example, an effusive thank you from the American painter Charles Arnoldi left me wondering what good deed needed repaying. Also for sale were two watercolours of Hawaii painted a decade after Didion published her confessional 1969 essay “In the Islands” in Life magazine. “We are here on this island in the middle of the Pacific in lieu of filing for divorce,” she wrote, her tone absent of sentimentality. Yet decades after her near-divorce, she’d still be decorating with the islands’ rainbows and frangipanis – paintings that can’t help feeling charged with personal meaning.

Didion was famously and uncommonly observant but she found journal writing to be tedious. “At no point have I ever been able successfully to keep a diary,” she wrote in the essay “On Keeping a Notebook”. “On those few occasions when I have tried dutifully to record a day’s events, boredom has so overcome me that the results are mysterious at best.”

But the auction objects, chosen by Didion, are a kind of diary of her domestic life. Broken-spined cookbooks and embroidered napkin sets suggest the meals she made and for how many. The books she received from famous authors – Michael Ondaatje and John Burnham Schwartz are among those who inscribed their “admiration” – formed a circle of flattering peers.

But I don’t need to own them to imagine what it felt like for Joan Didion to own them. How intimidating it may have been, upon her marriage into the well-to-do Dunne clan, to receive a monogrammed silver tea service from his family. I don’t need to own the yellowed quilt that hung over Quintana’s bed, in a bedroom that remained hers into adulthood, to understand the closeness implied. It’s enough simply to have had a look.