On Wednesday, I attended oral argument at the Supreme Court. While on the security line, I bumped into Joan Biskupic. She mentioned that she was publishing a new book, titled Nine Black Robes. I asked what it was about. She said the Roberts Court. I asked her to send me more information about the book. Biskupic then made it through the magnetometer and hustled to the press room. I went upstairs.

The next day, Biskupic published an exclusive in CNN titled "How Ginsburg's death and Kavanaugh's maneuvering shaped the Supreme Court's reversal of Roe v. Wade and abortion rights." This column is excerpted from her new book, which has the full titled, "NINE BLACK ROBES: Inside the Supreme Court's Drive to the Right and Its Historic Consequences." In the old days, when Biskupic published a bombshell, it went kaboom. We learned things that we couldn't figure out on our own. Now, her exclusives are barely there. At most, she confirms things that are fairly obvious. Or she tells us things that are sort of novel, but do not get to the heart of the Court's decision-making process.

Let's walk through the new column. First, Biskupic recounts that shortly after RBG's death, the Chief's office moved all of her belongings to the theater on the Supreme Court's ground floor:

Within days of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg's memorial service in late September 2020, boxes of her files and other office possessions were moved down to a dark, windowless theater on the Supreme Court's ground floor, where – before the ongoing pandemic – tourists could watch a film about court operations. Grieving aides to the justice who'd served 27 years and become a cultural icon known as the "Notorious RBG" sorted through the chambers' contents there. The abrupt mandate from Chief Justice John Roberts' administrative team to clear out Ginsburg's office and make way for the next justice broke from the common practice of allowing staff sufficient time to move and providing a new justice with temporary quarters if needed while permanent chambers were readied. But the confirmation of then-President Donald Trump's chosen successor, Indiana-based US appeals court Judge Amy Coney Barrett, was as much a fait accompli at the court as in the political sphere.

In September 2020, the Supreme Court building was a full house. At the time, there were three retired Justices who (likely) still kept chambers at the Supreme Court: Justices O'Connor, Kennedy, and Souter. (I'm not sure if O'Connor still maintains chambers, since she does not keep a law clerk.) Justice Stevens had died in April 2020. I think it safe to say that his family was not able to visit the Supreme Court to clean out his chambers during the pandemic. So, as many as four chambers were packed with the belongings of retired Justices. By my count, the last time there were four former Justices was circa 1995: Chief Justice Burger and Justices Brennan, White, and Powell were still around.

Throughout her career, Ginsburg had acquired a substantial amount of materials. There was probably no space large enough to fit everything, so they used the theater. (Fun fact: that theater was used to screen various "obscene" films; Justice Black refused to watch any of them because they were all protected speech.) Plus there was a pandemic, so staffing was short. And the Chief knew that a Trump appointee would arrive very shortly. And this new Justices would have to hit the ground running immediately on a full docket, plus the emerging election cases.

Biskupic tries to spin this administrative decision as a metaphor for Dobbs:

That behind-the-scenes drama and internal tensions over cases that followed, accelerated by all three Trump appointees, led to a new level of distrust and discord among the justices that lingers today. Almost as abruptly as Ginsburg's possessions were cast out, the court's 6-3 conservative majority began ravaging the vestiges of Ginsburg's work on women's rights and access to abortion.

The metaphor falls flat. Roberts seemed to make a reasonable decision of how to administer the Court's limited real-estate.

Next, Biskupic repeats the well-worn claim that Justice Kavanaugh tries to make himself appear "conciliatory":

The abortion controversy also surfaced a pattern of double-signaling to colleagues and people beyond the court by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, Trump's second appointee. Kavanaugh has long been concerned with appearances. He remains torn between his allegiance to conservative backers from his 2018 nomination fight and his desire for acceptance among the legal elites who shunned him. Since Kavanaugh joined the bench, a documented pattern reflects the lengths that he goes to in order to appear conciliatory.

I would state the issue a bit differently. I don't think Kavanaugh desires acceptance from legal elites. He probably knows that ship has sailed. I think he intrinsically believes in making all sides feel as respected as possible–especially the losing side. Kavanaugh's saccharine jurisprudence infuriates me. But this is who he is. And he behaved this way long before his Supreme Court confirmation. Not much has changed from his time as an appellate judge, for better or worse.

Biskupic does bring forth one new piece of evidence to back up this "conciliatory" claim:

A previously unreported example occurred in 2019, when Kavanaugh joined a dissent denigrating a US district judge for rejecting the Trump administration's attempt to add a citizenship question to the 2020 census form. A Supreme Court source revealed that Kavanaugh then quietly sent the judge a personal note saying he actually respected him. . . . The later Kavanaugh note to Furman showed his efforts to appear conciliatory: He joined an opinion challenging Furman's integrity but then wrote the judge a note that pleaded the opposite.

Here, Biskupic is writing about Department of Commerce v. New York. Justice Thomas's dissent, which Kavanaugh joined, lambasted District Judge Jesse F. Furman's rulings.

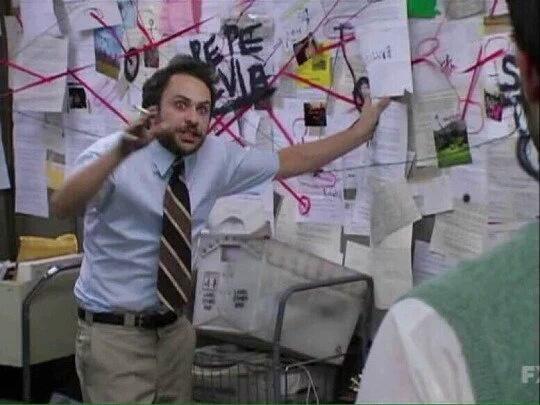

The District Court's lengthy opinion pointed to other facts that, in its view, supported a finding of pretext. 351 F. Supp. 3d, at 567–572, 660–664 (discussing the statements, e-mails, acts, and omissions of numerous people involved in the process). I do not deny that a judge pre-disposed to distrust the Secretary or the administration could arrange those facts on a corkboard and—with a jar of pins and a spool of string—create an eye-catching conspiracy web. Cf. id., at 662 (inferring "from the various ways in which [the Secretary] and his aides acted like people with something to hide that they did have something to hide").

At the time, I immediately thought of the Always Sunny in Philadelphia meme:

Back to Biskupic. Kavanaugh sent a letter to Judge Furman saying he respected him. Big deal! This may come as a surprise, but judges do privately correspond with each other. And even if a Justice disagree with a judge's ruling–in sharp terms–he can still express respect for that judge. Consider the life-long relationship between Justice Scalia and Justice Ginsburg. No matter how sharp Scalia's rhetoric was in opinions, he always expressed admiration for Ginsburg in public speeches as well as in private correspondences. Moreover, Kavanaugh is a nice guy. Believe it or not, he and I actually used to get along quite well. He even volunteered to judge the high school moot court competition I run. From time to time, Kavanaugh would send me gracious notes about this or that. Sending this letter to Furman is entirely in keeping with who Kavanaugh is as a person. Another non-story, spun up to make a broader point.

The closest thing we have to a scoop concerns the fetal heartbeat case. Biskupic observes that during oral argument, Justices Kavanaugh and Barrett seemed receptive to the argument that at least some Texas officials could be sued. (I responded to that position, vigorously, here.)

Kavanaugh particularly questioned whether, if states could block abortion rights, they could do the same for firearm rights and free speech. Barrett sounded troubled that the Texas law was written in a way that would deny any challenger a "full constitutional defense." Their remarks were widely interpreted by outside observers to suggest they were ready to rule against Texas and to allow abortion clinics to challenge the law preventing abortions after about six weeks. More importantly, some of the justices who believed that law blatantly unconstitutional interpreted their colleagues' comments that way, too, and believed there would be a turning point in the Texas case. But when the votes were cast in private, the justices on the left realized they had been misled by what they had heard in public.

I don't know what to make of this sourcing. Biskupic seems to be reflecting on what some of the Justices "believed." And to be precise, the Justices who thought the law was "blatantly unconstitutional" were Justices Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan. So tracking down the source of this information should be straightforward. But there is no sourcing! No "Supreme Court source" or "sources close to the Court" or anything. We have no basis to support this claim. And the second sentence seems implausible. Would Justice Breyer, Sotomayor, or Kagan really claim to be "misled" based on what questions a Justice asks during oral argument? Did they not live through the Obamacare case? Justices can change their minds. This entire claim strikes me as too thin to give much attention.

Next, Biskupic reflects on how the leak "froze" the votes in place:

The leak also had the effect of hindering internal debate among the justices in the Dobbs case. Justices later privately revealed that public disclosure of the 5-4 split and the tone of the opinion outright rejecting Roe v. Wade effectively froze the votes. That eliminated the opportunity for compromise, as can happen with hard-fought cases in the final weeks of negotiation.

I speculated that this was a likely consequence of the leak. We don't know who the Justices (plural) "privately revealed" this fact to, but Biskupic received such hearsay, indirectly. And nothing here is particularly revealing.

Is there drama and tension inside the Court? Who knows. Nothing in this column backs up those claims. Gone are the days that Biskupic told us things we didn't already know. I pre-ordered a copy of the book on Kindle. I'll let you know if there is anything newsworthy.

The post Joan Biskupic's Barely-There Exclusives appeared first on Reason.com.