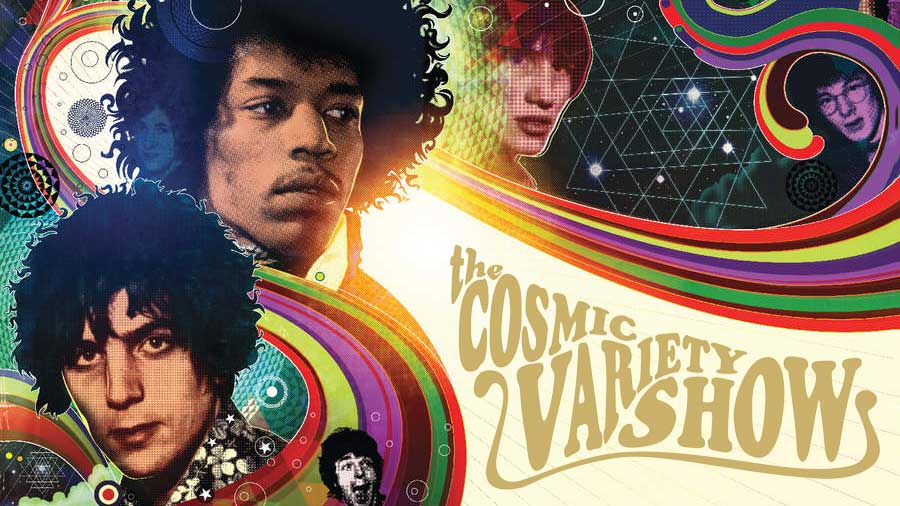

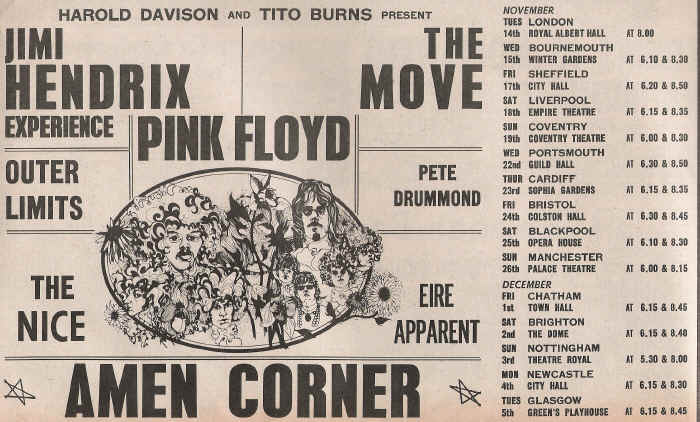

In November 1967 a star-studded but unlikely assemblage of psychedelic, rock and soul bands set out in a fleet of cars, transit vans and coaches on a 21-date tour of theatres and civic halls the length and breadth of Britain in a vague attempt to emulate the traditional ‘package’ tour of yesteryear.

Veteran music biz promoters Tito Burns and Harold Davison, who promoted the tour, knew the economic value of the theatre package tour well – they’d made a business out of it. But the combination of bands drawn up for this tour was a bit way-out even for those times.

This wasn’t a package tour featuring end-of-pier comedians or cabaret acts, this was a bill featuring the cream of the new music: some of the craziest, most pioneering and – it would turn out – influential bands of all time: the Jimi Hendrix Experience and Pink Floyd, supported by The Move, The Nice, Amen Corner, Eire Apparent and The Outer Limits.

Future Stiff Records co-founder Dave Robinson was Eire Apparent’s Road Manager. “In 1967 you were beginning to get the ‘album artists’,” he said. “More musical, get your rocks off. So it was the last of those kind of tours. Prior to that it was people doing their little three-minute numbers from Top Of The Pops, really. So you had The Move, who were kind of single-y but also had delusions of musical grandeur, and The Nice, who although they had 12 minutes, usually played just one number.”

These days a similar bill would sell out stadiums in a flash. But there were no guarantees back in 1967. Promotional touring didn’t exist back in the 60s, bands just accepted the fact that if they weren’t in the recording studio their management expected them to be out on the road.

For the Jimi Hendrix Experience this would be their second full tour of the UK, having spent much of the summer months in mainland Europe and the US basking in the glory of having played an awe-inspiring, now legendary, set at the Monterey festival. Hit singles had ensured much anticipation – Hendrix went from zero to hero in a matter of weeks.

Pink Floyd, meanwhile, did the reverse: they took an unhealthy delight in frightening their audiences into submission, or disgust, and although they had enjoyed chart success their career was hanging in the balance.

“We could clear halls so fast it wasn’t true,” recalled Nick Mason. “I mean, they were outraged by what came round on the revolving stage and they lost very little time in trying to make this clear.”

The show was comprised of two halves with an interval. Newcomers the Outer Limits and Eire Apparent opened with just eight minutes apiece; Amen Corner were next up with 15 minutes, and The Move closed the first half with a 30-minute set. After a 20-minute interval The Nice were next, followed by Pink Floyd, with 15 minutes each. Hendrix closed the show, with an incendiary 40-minute set.

It didn’t give the bands much time to prove themselves but it was good promotion, as The Move’s manager Tony Secunda later recalled: “The idea was to cram as many bands on to the bill as possible, not simply because it made financial sense but also because it gave massive exposure to bands who might never get out there.”

Speaking to many of the participants in 2007, what seemed remarkable about this particular 1967 tour is just how ‘nice’ it all was.

“The whole thing was that time of ‘peace, love and brown rice, man’ and all that stuff,” recalled Bev Bevan, then drummer with The Move. “A lot of the guys were getting stoned. It was a very peaceful tour.”

“Everybody was mucking about,” recalled The Nice’s Keith Emerson. “It was like a huge school trip.”

A school trip with knife-throwing, instrument smashing and acid-related breakdowns, that is.

Holding the cavalcade of artists together on stage was the compere, BBC Radio One DJ Pete Drummond. Like many of the pop DJs of the time, he enjoyed a secondary income from playing records and introducing artists at festivals, all-nighters and tours such as this. With so many change-overs, Drummond was left to fill-in between bands.

“I had to stand there and say: ‘It’ll be a few minutes before the next band… And being here in Glasgow reminds me of the Scotsman who…’ and just go into some joke. Nine times out of 10 they’d just shout out ‘Fuck off!’ It was no ego boost for me. Hendrix used to say: ‘Did you hear me tonight? I was out the back yelling “Fuck off!” early on!’ Yeah, I heard you, Jimi.

"I'’m getting that audience so wound up against me that you could be the shit worst player on earth and they’d love you! Roger Waters – especially Roger – used to come up to me and say: ‘I’ve got a good joke for you today.’ I had the salient words of jokes written on my wrist.”

“It was a showcase for bands riding on Hendrix,” Drummond said. “I think he got half the gate and everybody else was on fixed fees. I think [Jimi’s bassist] Noel Redding and the drummer, Mitch Mitchell, were salaried. I was on £25 a night and, apart from Hendrix, I had more money than anybody. Even though [The Floyd] were second headliners on this tour they weren’t earning money. I had to buy food for bands – curry and chips for the Amen Corner when we hit Cardiff. I think the Floyd earned about £20 between them per day, so they weren’t that bad.”

Being the opening act was never going to be an easy task for anyone, but Irish group Eire Apparent rose to the challenge. They began life in early ’67 as a show-band called The People, and found themselves scratching a dead end living in Dublin, before making a break for London. There they ran into an old acquaintance from back home: the aforementioned Dave Robinson.

Eire Apparent got a gig at the UFO club in London supporting Procol Harum. They impressed Chas Chandler, the Animals bassist and manager of Jimi Hendrix and Soft Machine, to the extent that he and his business partner Mike Jeffrey were later banging on the band’s dressing room door offering them a management contract.

“It was to be a joint venture then,” Robinson recalled. “I was running the band but they would have 50 per cent of it, and would do the office work, the administration. So I ran around with the band on the road and they looked for the main chance for us to become big. And because of Jimi Hendrix we were able to get through a lot of doors. It was a very opportune connection.”

“When you’ve got somebody like that behind you it’s not the money, it’s the upward move in the music business,” remembered Eire Apparent’s guitarist Henry McCullough. “We had to sit in their offices and wait for someone to give us £20 so we could go and eat. That’s how well signed up we were!”

“That was a great apprenticeship,” Robinson laughingly recalled. “Chas Chandler was very musical, being the bass player from The Animals, so I learnt a lot from him about presenting the group, live, mainly. And Mike [Jeffrey] was the very canny, very cunning manager-type person who was obviously up to no good most of the time.”

For the four young lads out of Belfast it was a steep learning curve, performing alongside some of rock’s royalty, and doubtless also a fast-track education in the rock-star lifestyle. (“You know,” said McCullough, “if you’re on for 15 minutes you’ve got 23 hours left in your day. And with not being at home you could end up anywhere. Not only physically, but mentally.”)

After the tour, Eire Apparent played a regular support to Hendrix across Europe and the US, and Jimi produced their second album, Sunrise. But lasting success was not to be. In 1968 McCullough was thrown out of Canada for possession of marijuana and was forced to quit the band. These days he’s best remembered as a member of Joe Cocker’s Grease Band and Paul McCartney’s Wings.

The remainder of the group failed in their attempt to re-establish themselves in the UK after such lengthy tours abroad, and split in 1969. Vocalist Ernie Graham later joined Clancy and then Help Yourself; drummer Dave Lutton played in T. Rex through the mid-70s, and bassist Chris Stewart joined US band Poco.

Probably the least well-known band on that tour of ’67 tour were founded at Leeds University that same year. The Outer Limits were the Rolling Stones’ flamboyant manager Andrew Oldham’s hot new signing to his Deram/ Immediate record label.

Their debut single, Just One More Chance, was released in June, and it was probably just about all they had time to play in their slot. Unfortunately for them their second single, The Great Train Robbery, released in early 1968, was considered distasteful by the BBC, even five years after the actual event, and the band never fully recovered. (Frontman Jeff Christie did, however, find lasting fame as the composer of the song Yellow River which he took to No.1 in the UK chart, for what seemed like forever, with his band Christie in 1970.)

If The Outer Limits had their, well, limits, arguably one of the most talented acts on the bill was the seven-piece Welsh blues-soul outfit Amen Corner. Despite having released only one single at the time of the tour, Gin House Blues, on Deram, in the summer of ’67 they were seasoned musicians, having gigged constantly throughout Britain. (Singer Andy Fairweather-Low is still gigging today, playing guitar with the likes of Eric Clapton, Bill Wyman and Roger Waters – a post he held for more than 20 years.)

“Our manager, Ron King, was very persuasive,” Fairweather-Low remembered. “Roger Waters remembers our first meeting. He said: ‘Your manager screamed at me because I shouted at one of you. Ron said: “I’ll break your fucking legs.”’ And, believe me, when Ron said: ‘I’ll break your fucking legs,’ he would! It was a real possibility that it would happen. Roger remembered that. I didn’t remember any of that. But our first introduction [to the music industry], we went straight into Don Arden and Ron King… So that, to us, was normal.”

Former Amen Corner sax player Allan Jones was in awe of Hendrix. “I remember Newcastle City Hall,” he said. “Jimi was very often out of tune, because he used to bash his guitar around like crazy. And he may have been a little bit out of it and didn’t quite tune up his guitar properly before he went on, or whatever. And he was constantly going out of tune. This night, he was playing his Gibson Flying V and he was so pissed off with the tuning that he actually took the guitar off his shoulder and threw it at the Marshall stack. And it fucking landed in the stack. The place just erupted and went fucking ballistic! It was a one-off. It was one of the most incredibly exciting moments I can remember.”

Such wild performances put many of the other bands in the shade; for Amen Corner it became an inspiration. Halfway through the tour Amen Corner were proving so popular that, at Chas Chandler’s insistence, they exchanged places with The Move and closing the first half of the show with their ‘Otis Redding revue’.

Less than two years later Amen Corner called it quits. Sax players Allan Jones and Mike Smith went on to form Judas Jump, while the rest, led by Fairweather-Low, formed the band Fair Weather. Drummer Dennis Byron and keyboard player ‘Blue’ Weaver later become part of The Bee Gees’ band.

It would have been difficult not to have been aware of The Move back in the autumn of 1967. Their manager, Tony Secunda, had a fearsome reputation for publicity seeking, and made damn sure The Move were in the news at every possible opportunity.

Secunda’s failing was that he didn’t know when to stop. When he publicised the Move’s third single, Flowers In The Rain, with a postcard featuring an image of the then Prime Minister Harold Wilson in bed with his secretary Marcia Williams, it resulted in a High Court ruling that all royalties from the single be paid, in perpetuity, to a charity of Wilson’s choice.

The Move’s troubles were compounded by the fact that they had their own version of Syd Barrett in the band in the shape of ‘Ace’ Kefford, their gifted bass player. His spates of crippling depression, more than likely aided by his intake of LSD in this period, began to blight his life, and he never fully recovered.

That aside, there was much at stake. A friendly rivalry co-existed between the Jimi Hendrix Experience and The Move, and it’s hard to say who was most likely to upstage who at this point in the billing. Hendrix had the passion, but The Move had scored four top 10 hits against Hendrix’s three. This often resulted in the usual practical jokes that touring band’s are prone to playing on each other, partly to relieve the boredom of touring.

“I remember The Move playing once, and I rode a bicycle across the stage,” Noel Redding once recalled. “Another time we put stink bombs in Bev Bevan’s bass drum pedal.”

The Move also had one other trick up their sleeve: the anarchistic stage antics of Carl Wayne. At one particularly memorable show at the end of the previous year, they shared the billing with Pink Floyd and The Who.

“At the Roundhouse, Carl Wayne smashed an all-American, psychedelically painted Cadillac convertible with an axe, with two strippers on the roof as he was doing it!” recalled Bev Bevan. TV sets and busts of Hitler were routinely smashed to pieces as well. Unsurprisingly, The Move were kicked off a tour supporting The Walker Brothers. Like most of the bands, The Move found a spiritual home on that legendary package tour of ’67.

“It was probably the strangest and maybe the best tour I’ve ever been on,” Bevan recalled fondly. “I think we’d stopped smashing up the TVs by then – it wasn’t the right venues for that, really. We were fans of Hendrix, and Trevor [Burton, The Move’s rhythm guitarist] particularly got to know Hendrix very well and went on to share a flat with Noel Redding, and I got to know Mitch [Mitchell, the Experience’s drummer]. They were the most extraordinary trio to watch on stage. We used to watch them every night and say: ‘You wouldn’t want to follow that!’

“What a lovely guy he was,” Bevan said of Hendrix. “On stage he was this absolute animal. But off stage he was very soft-spoken, and whenever a woman would walk into the room he would stand up and offer his chair. He had lovely manner, and not what you’d expect at all.”

Trevor Burton had the time of his life. “It was insane! Insanity!” he laughed enthusiastically. “There was a coach but The Move and Jimi Hendrix had their own transport. I travelled mostly with Jimi on that tour because The Move used to go home every night, wherever they were, because they all had girlfriends. I didn’t, so I travelled with Jimi most of the time. It was great. Pretty stoned!”

“The Move were very funny,” Dave Robinson recalled. “I remember a situation at soundcheck and overhearing Carl Wayne. He’d turned up late to the soundcheck because he’d been having his venereal warts removed!”

The Move fragmented in the early 1970s, initially with the departure of Trevor Burton and then singer Carl Wayne. Roy Wood formed Wizzard and, together with Bev Bevan, also enjoyed phenomenal success with the Electric Light Orchestra.

Like many of their tour-mates The Nice were relative newcomers, barely four months into their solo career (they had originally been formed as singer PP Arnold’s backing band) and with just one hit single to their name.

Despite their lack of recorded output, The Nice had already garnered a wealth of rave reviews following their anarchistic take on prog rock, classical and jazz improvisations. Where The Move had by then toned down their on-stage antics, The Nice’s keyboard player, Keith Emerson, was building his up. The audience was going to get a hell of show.

“He was the only stand-up organist doing wild things with his organ as Pete Townshend and Jimi did with their guitars,” said The Nice’s guitarist Davy O’List. “Our audiences went wild. I wore a velvet bell jacket I had designed, reminiscent of a jester, and I lent Keith a whip to whip his organ with; bells, doves and whips coming out and flying about in red smoke.”

Emerson also had a routine of throwing knives at his Hammond organ and wedging them between the keys to sustain the notes. “First it was going to be swords but they were too big to handle,” mused O’List.

In the days before Motörhead, Lemmy Kilmister worked as a roadie for The Nice. When the package tour came around he was snapped up by Hendrix and earned a handsome £10 a night for the pleasure of humping his gear on and off stage.

Dave Robinson remembered Lemmy well. “He did no work at all!” he exclaimed. “I got to do quite a bit of his work for Jimi, because he was very busy signing autographs and swanning about outside with the girls. He’d been in a band called the Rocking Vicars and they were quite famous in the north of England, so he spent a lot of time swanning around and did absolutely… nothing!’

“The thing I remember about Lemmy,” Keith Emerson recalled, “is that when I started using knives he said: ‘Well if you’re going to use knives, use a real one,’ and he gave me a Hitler Youth dagger.”

Emerson also recalled one particular night that the knife-throwing could have ended in tragedy: “Jimi Hendrix had bought one of the first home movie cameras. During The Nice’s act, particularly in Rondo, I remember I’d stuck knives into the keyboard and was in the process of throwing them towards the two speakers when, in between the two speakers was Jimi.

"He’s got his camera and he’s filming me, and I kind of froze mid-throw, so to speak. And Jimi had his tongue out, and was beckoning me to actually throw them at the speakers while he was in the middle, while he filmed it. I thought: ‘I don’t want to be the one that puts him in the history books!’

O’List quit The Nice in mid-1968, and played briefly with Jethro Tull, early Roxy Music and then Jet. The Nice played their last show in 1970. Bassist Lee Jackson formed Jackson Heights, after which he reunited with drummer Brian Davison to form Refugee. Keith Emerson enjoyed phenomenal success, of course, with prog-rock supergroup Emerson, Lake And Palmer.

Quite how Pink Floyd talked their way onto the bill is anyone’s guess. Their leader, Syd Barrett, was slowly but surely undermining everything the band had strived to achieve over the past year. The endless touring, the photo shoots, interviews, radio and TV sessions would all be for nothing as it became increasingly obvious that the band’s chief songwriter just couldn’t cope any more, thanks mostly to having acquired a taste for LSD.

Despite a period of recuperation for him that August, the relentless touring frayed both Barrett’s fragile state of mind and his bandmates’ tempers in equal measure. On a US promotional tour just two weeks prior to the start of the Hendrix tour the Floyd well and truly screwed up three high-profile Hollywood TV appearances, rubbed legendary San Francisco promoter Bill Graham up the wrong way and reduced the MD of their record label in Los Angeles to tears.

“Detuning his guitar all the way through one number, striking the strings. He more or less just ceased playing and stood there, leaving us to muddle along as best we could,” said Floyd drummer Nick Mason. “Syd actually went mad on that first American tour. He didn’t know where he was most of the time. I remember he detuned his guitar on stage at Venice, Los Angeles, and just stood there rattling the strings, which was a bit weird, even for us. Another time he emptied a can of Brylcreem on his head because he didn’t like his curly hair.”

Pink Floyd desperately needed this tour in order to maintain their profile in an increasingly difficult environment.

“Basically, they [Pink Floyd’s management] were worried about Syd Barrett,” said Tony Secunda, “but needed to keep the band’s name out there, but nobody knew if Barrett was up to it. The general feeling was that he wasn’t.”

“Syd had left the universe,” said The Move’s Trevor Burton. “‘Put a mark on stage for him to stand’, you know. ‘Don’t move!’ Henry McCullough used to do parts for him,” Burton laughed. "He’d be standing on the side of the stage doing Syd’s parts while Syd was gazing off into the distance.”

During the course of the ’67 tour Barrett would often wander aimlessly around the town they were visiting, and either stand on stage limply or not appear at all. The opt-out clause for Pink Floyd was to string out a new Roger Waters composition called Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun, or perform instrumentals such as Pow R Toc H or Interstellar Overdrive from their debut album, with or without Syd. Pink Floyd’s light show was also an asset – something they could hide behind.

Secretly the band were already thinking of how to replace him. And Nice guitarist Davy O’List looked a very likely candidate.

“I’d watch them every night and I learned their songs,” O’List said. “One night I stood in the wings so they could see me enjoying the music. Syd went off on a walk one night and didn’t come back. I knew their music and I said I could perform it well, so they asked me on.”

It may have been an audition of sorts, but Pink Floyd soldiered on regardless. Their third single, Apples And Oranges, was released on November 17, early in the tour, but it failed to make any ground on the UK chart – which is as a good an indicator as any of the impact their set was having on audiences.

Barrett continued his downward spiral and almost consigned the band to the dustbin of history with his wayward antics. Had it not been for Roger Waters taking the lead after the ’67 tour it could well have been the end of Pink Floyd.

“To be honest with you, the Floyd were very aloof,” said Amen Corner’s Allan Jones, “very much into their own thing. And at the time, I have to say I wasn’t that impressed with them. They never seemed to be in tune and it was all very disjointed. It didn’t do anything for me live, but I loved the singles.”

Andy Fairweather-Low agreed: “You know, ‘aloof’ and ‘insular’ are two very good descriptive words of how we felt about them, then. What they thought about us I haven’t got a bloody clue! And Syd I remember as being not really part of the team. We all travelled – the majority travelled – on one big bus. The Floyd travelled separately. And I think they travelled separately themselves too. I don’t think there was any great bonding going on there.”

“The Floyd didn’t mix at all, with anybody,” said Burton. “They were all like arty student types and we were fucking hardened rockers, you know, and they kept themselves to themselves. Noel and me quite often would go into their dressing rooms and try and communicate, but it didn’t work very often.”

“They weren’t inclined to socialise,” confirmed Keith Emerson. “I do recall one moment on the tour of overhearing Roger Waters ask the rest of the band: ‘Well, when is it your turn in the studio?’ And I asked Roger: ‘What? You don’t all go in the studio together?’ And he said: ‘Oh, no, no, no. If we go in separately it avoids arguments.’”

Syd Barrett’s time in Pink Floyd was all but over by the conclusion of the tour. He was replaced by David Gilmour in early 1968.

Within mere weeks of his arrival in London, Jimi Hendrix’s legend was secured. Here was a guitar player that turned the world of rock music on its head and left contemporaries Pete Townshend and Eric Clapton weeping in disbelief at his virtuoso skill. Despite his 1966 Top 10 hit Hey Joe, Hendrix was still largely unknown in the provinces before this tour hit the road, having played very little in his own right outside of London up until then.

Something of a misjudgement had also put him on a package tour in early ’67, coincidentally also organised by Tito Burns, that placed him alongside The Walker Brothers, Engelbert Humperdinck and Cat Stevens – exposing him to exactly the wrong audience. A series of patchy regional club gigs followed but Hendrix was yet to achieve widespread fame.

That, however, changed very rapidly. With the release of two further singles – Purple Haze in March and The Wind Cries Mary in May – Jimi was rapidly building up momentum. In the months that followed he steadily increased his international following, first in the US and then in Europe. He had turned in an explosive set at the Monterey Pop festival in June which left his co-stars The Who (and most of the audience) completely dumbfounded, leaving The Who little option but to end with a demolition finalé.

Come the tour, Hendrix did not disappoint. A sold-out Royal Albert Hall felt the full force of his set as the Experience powered through Foxy Lady, Fire and The Burning Of The Midnight Lamp. A preview of the yet to be released Spanish Castle Magic was followed by the brief respite of The Wind Cries Mary, and the band ended their set with a ferocious Purple Haze. This was Hendrix, Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell at their best: a short, snappy, blazing set – a power trio with the world at their feet.

Keith Emerson was blown away: “Everybody involved in the tour, they’d all come back in the wings and watch him because every night he played he’d do something completely different. And a lot of times he astounded Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell, because they didn’t always know what he was going to do. He was certainly trashing a lot of speakers. I remember him playing the Flying V guitar for the first time, and he threw it and it actually landed like an arrow into the speaker cabinet, and us backstage watching from the wings were just completely, ‘Wow!’”

Hendrix may have been the wild man of rock but he also showed incredible humour and patience for less-than-grateful fans. Keith Emerson recalled a night in Bristol: “At the end of the show I remember a lot of the fans managed to get backstage – the security wasn’t very good at all – and they crashed into our dressing room with their autograph books. And of course we were very disturbed about having our privacy invaded like that.

"I think The Move decided to sign, and then the fans wanted everybody’s autograph. And on the way out one of the autograph hunters turned to Jimi and said very loudly, so that we all heard: ‘I think Eric Clapton is much better than you.’ There was a kind of hushed silence that went over the dressing room. Then Jimi turned back and said quite politely: ‘Well, I think Eric’s a far better guitar player too.’”

Emerson also recalled the only time there were any bad vibes on the entire tour. “Jimi went a little bit wild swinging his guitar around and he actually managed to hit Mitch Mitchell’s bass drum,” he said. “Mitch protected his drum set like it was gold, and he was pretty much crying after the show, going: ‘You shouldn’t have done that! You’ve got no respect for my drums!’ He was really distraught.”

The end of the tour also marked the end of an era. It is widely regarded as the last of the great pop-rock package tours; a phenomenon unique to the times. 10 years later, recognising the strength of the format, Dave Robinson modelled the first Stiff Records package tour in 1977 on that ’67 tour.

Thereafter the idea remained largely forgotten, but it resurfaced and has become appealing yet again: Lollapolooza, Ozzfest, Knotfest, and the Vans Warped Tour can be traced right back to the Hendrix package tour of November 1967.

Thanks to Allan Jones, Andy Fairweather-Low, Bev Bevan, Trevor Burton, the late Henry McCullough, the late Keith Emerson, Davy O’List, Keith Altham and Dave Robinson. The original version of this feature appeared in Classic Rock 114, in January 2008.