His most famous images came while perched in what amounted to a journalistic deer blind at a dive bar on the Near North Side.

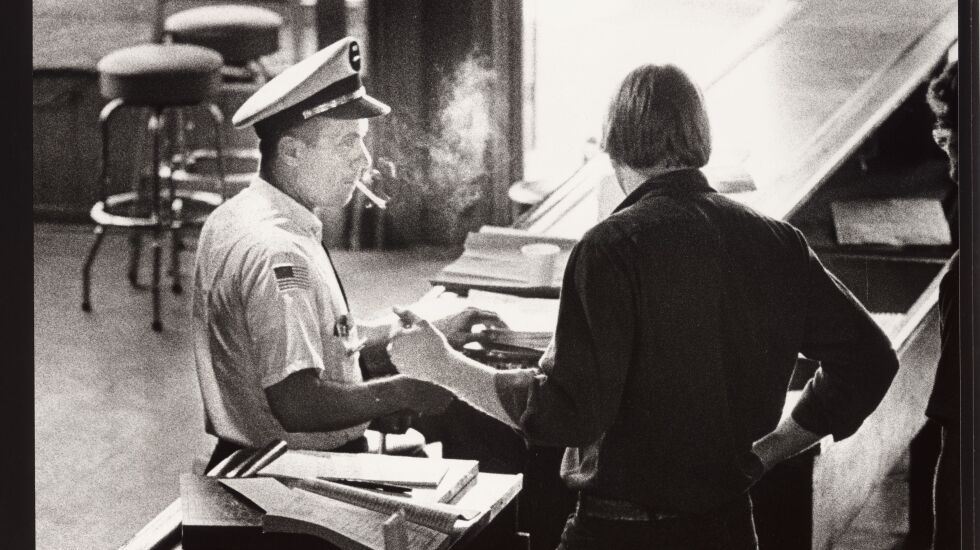

The game he was hunting: crooked city of Chicago inspectors.

It was all part of what came to be known as the Mirage tavern sting.

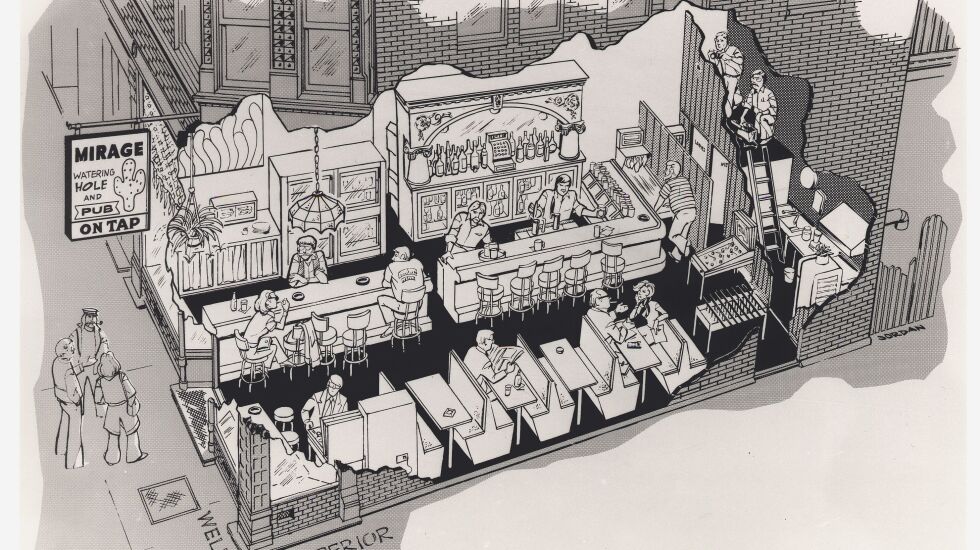

It took place inside a bar the Sun-Times bought in 1977, staffing it with reporters posing as workers in order to blow the lid off the culture of corruption involving city inspections.

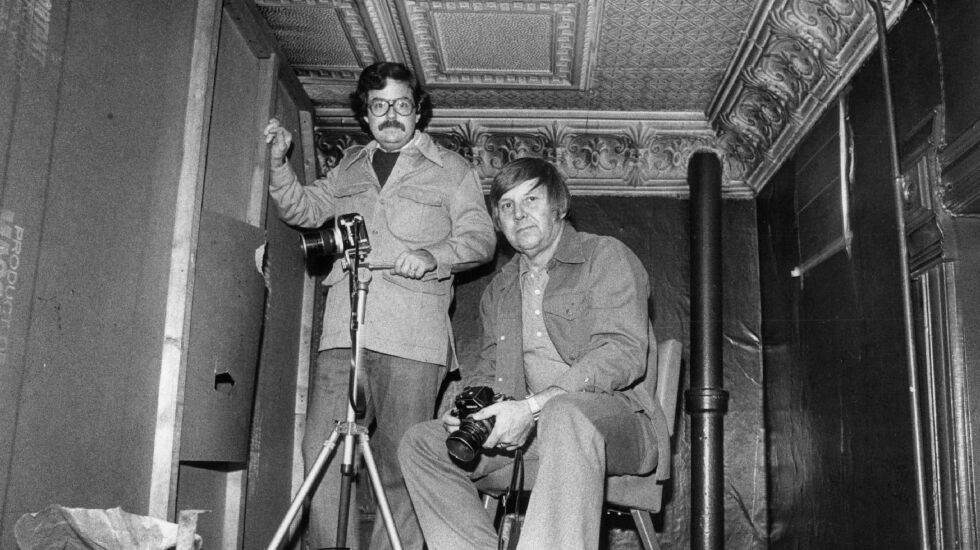

In a lofted space in a back room at the bar, Mr. Frost cut a hole in the wall and covered it with a vent. From there, he and another Sun-Times photographer, the late Gene Pesek, secretly documented it all with their photos. The vent was new. But that wouldn’t work, Mr. Frost realized.

“I took it home, and I beat it all up because it was not a pretty place, and a shiny vent would have been out of place,” he told the Sun-Times last year in an interview for his fellow photographer’s obituary. “The whole thing was hanging on me and Gene in a big way.”

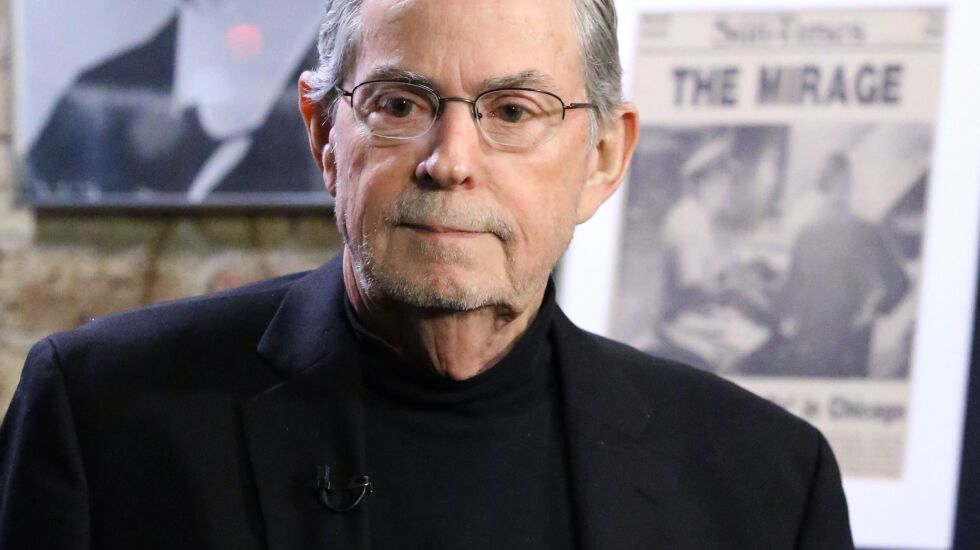

Mr. Frost died March 1 after a stroke. He was 79.

Posing as a repairman, Mr. Frost would carry his camera equipment in a toolbox. He’d walk in and say something like “that fuse box again?” and disappear into the back, he recalled for the book “Chicago Exposed” that was published last year.

He kept the ruse alive when a plumbing inspector nearly discovered his secret spot.

The inspector was fumbling for a light switch in a back room when an undercover colleague yelled for him to stop because it would blow a fuse. The ploy gave Mr. Frost time to scramble up a ladder and hide the equipment beneath a tarp under the guise of searching for a flashlight.

“My heart was in my throat,” said former Sun-Times reporter Pam Zekman, who played the role of a young bar owner. “Jim saved the day. The whole thing could have been blown.”

The sting produced a 25-part series that ran for weeks and birthed a legend that’s recounted in journalism textbooks to this day.

“My favorite headline was ‘The envelope please . . .’ and showed an inspector holding the envelope,” Zekman said.

Mr. Frost would make sure the jukebox was turned up loud so the click of his camera’s shutter wouldn’t be heard.

He was a recent hire from the Daily Herald when his Sun-Times bosses called him in for a hush-hush meeting and offered him a yes-or-no choice on an important assignment that they would say nothing more about until he committed.

“I was chosen because I was the new kid in town, and none of the City Hall types would recognize me,” Mr. Frost recalled for the book.

“Not even my mom knew,” said his son Robert Frost. “He couldn’t tell her. He was so new at the time, he would have done anything. It was his dream job.”

Mr. Frost grew up on a dairy farm near Wisconsin Rapids, Wis. His house was heated, but Mr. Frost’s father used the heat sparingly to save money.

“My dad said he’d put a glass of water on his bedside table, and when he woke up in the morning, it was frozen,” Robert Frost said. “When he was 10, he’d herd the hogs through the woods with nothing but a bullwhip and a slingshot he made from a bicycle tire. These were 300-pound hogs. He said you had to hit them on the nose, or else they wouldn’t pay attention to you.”

After high school, Mr. Frost developed an interest in photography when a friend who worked at a print shop showed him how to develop film. He later worked at a local paper, where he won several photography awards, until he got a job with the Daily Herald in Arlington Heights.

While working there, photos of his of a train crash that outdid the competition caught the attention of the Sun-Times and helped get him a job, his son said.

Mr. Frost worked the street as a general assignment photographer, which, in an era before cellphones, meant carrying a beeper and finding a pay phone to check in.

“If he got beeped while driving in a particularly rough neighborhood, he’d floor it into a gas station, screech to a stop by the pay phone and leave the door open and the car running as he ran to the phone. ‘It looks so crazy, everyone thinks you’re a cop and won’t mess with you,’ ” Robert Frost remembers his father saying.

In 1979, Mr. Frost covered the crash of American Airlines Flight 191, which went down in a grassy field seconds after taking off from O’Hare Airport, killing 273 people.

He kept a piece of molten metal from the crash, always kept a pair of heavy boots in his car after that and would choke up at the memory of what he’d seen.

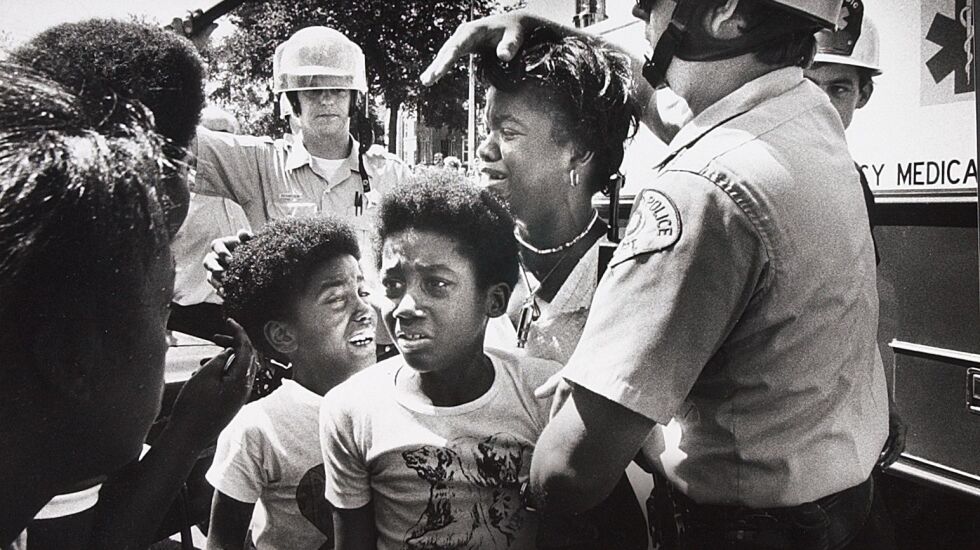

Mr. Frost’s daughter Shelley Groh remembers talking to her dad about images he captured of a cop protecting a Black mother and her children with his shield from projectiles being tossed at them by neo-Nazis who’d gathered in Marquette Park in 1978.

“I said, ‘Dad, who was protecting you?’ ” she said. “It was just amazing to me that he put himself in these situations. But he said he felt such a responsibility to be the eyes for the public to see what they couldn’t see on their own. And that blew my mind.”

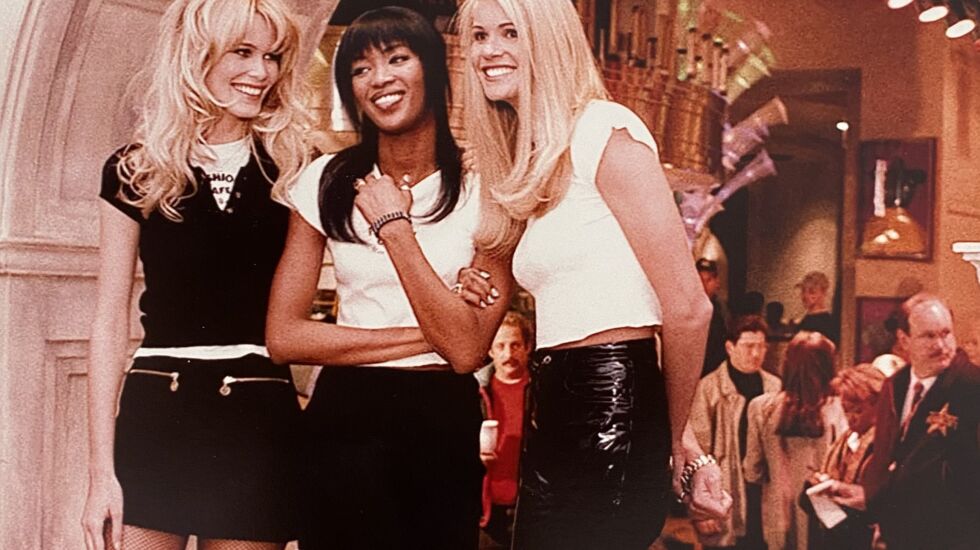

In 1981, Mr. Frost transitioned from shooting breaking news to handling food and fashion photography for the Sun-Times. In that role, one of his earliest shoots was at the Sun-Times studio with a teenage model from DeKalb who’d go on to great fame — Cindy Crawford.

Leaving behind news for that work was an easy call, his wife Lynne Frost said: “It was sort of: Go sit outside John Wayne Gacy’s house for days in the cold to get the shot of bodies being carried out from under his house — which he did — or go to Paris and shoot gorgeous models? What’s more fun?”

He attended fashion shows in New York, Milan and Paris, where he quickly learned to navigate the space at the end of the runway known as the pit.

“In Paris. I remember Dad saying it was rough and tumble, and there was a pecking order, and he was this new guy and didn’t speak French, and he’d go in but was only 5-foot-7, and he kept getting elbowed out,” his son said.

Mr. Frost quickly identified the ring leader in the pit and found out his drink of choice: Scotch. The next time, he arrived at the pit with a bottle and glasses that were quickly clinked as he proposed a toast.

“After that, he was one of the gang, and they let him through,” his son said. “He just had a way of figuring out a situation.”

“It was cutthroat, but he always managed to get the shot,” former Sun-Times fashion editor Lisbeth Levine said. “I’m not sure how he managed to expense the Scotch, though.”

Bev Bennett, a former food editor for the newspaper, remembers giving him strange ideas for a photo shoot.

“Jim would give me this look, like, ‘How do we do this?’ ” Bennett said. “But he’d pull it off every time.”

He’d spritz produce with water to get that just-right glisten in the glow of his lights, with a background of a particular marble or wood.

“We’re creating an atmosphere on top of the table,” Mr. Frost said in a Sun-Times story that offered a behind-the-scenes look at how it was done. “That’s what’s fun. We’re giving motion to something that’s still. We bring it to life.”

“Not for a minute was it lost on him that he was this kid from the farm,” his wife said. “He always said, ‘I just can’t believe the kind of life I’ve been allowed to live.’ ”

In addition to his wife and two children, Mr. Frost is survived by four grandchildren.

A visitation is planned for 10 a.m. March 25 at Calvary Community Church in Lake Geneva, Wis., with a memorial service immediately after.