In the second of this three-part series on the tradition and innovation behind Japanese hair art (our journey began with geiko wigmakers in Kyoto), photographer Prissilya Junewin and writer Makoto Kikuchi travel to Osaka to visit hairstylist Yumeko Yume, whose niche salon specialises in styles from the 1960s and 1970s.

Hair Salon Yumeya, Osaka: niche and conceptual

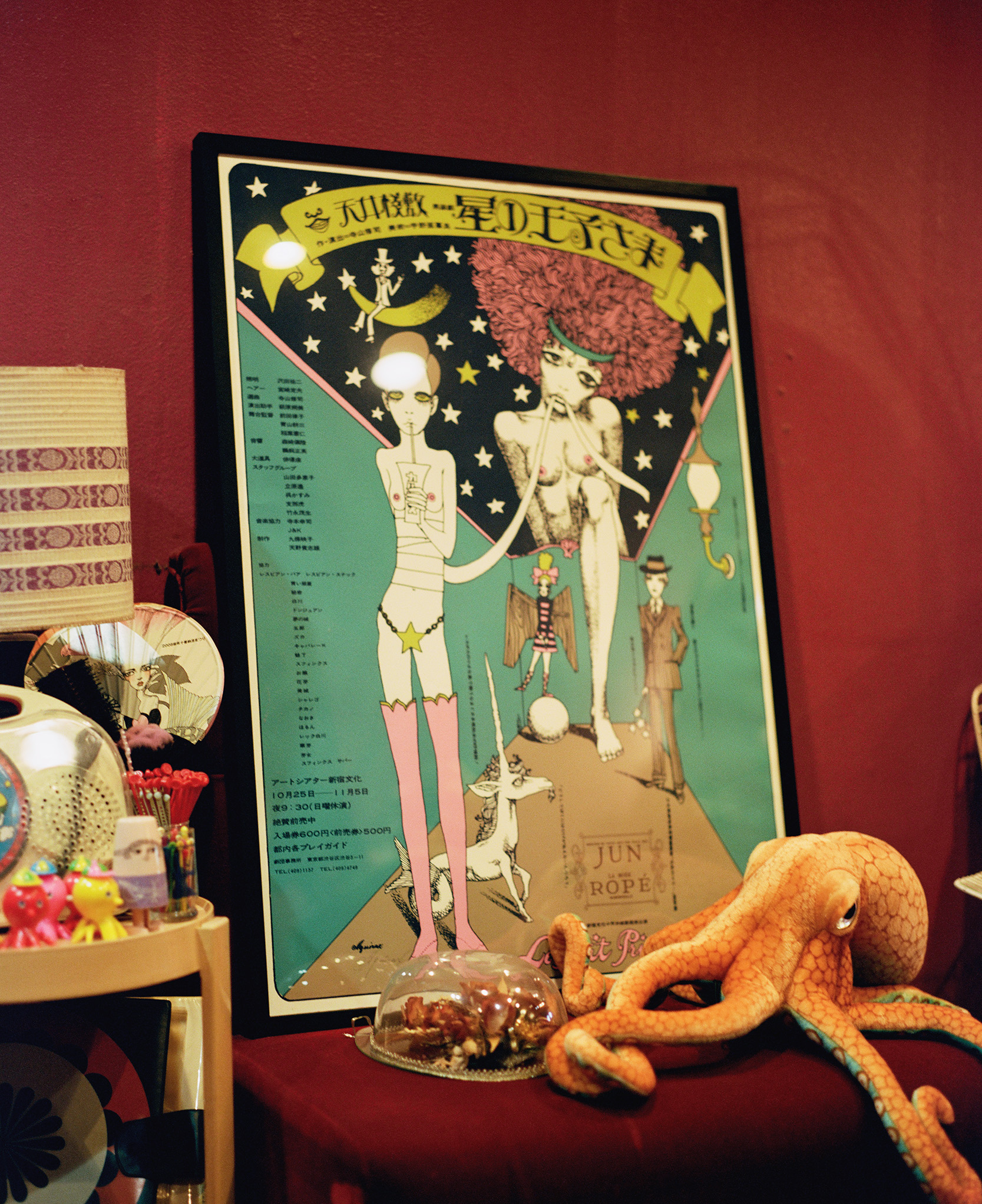

Located in a building in Shinsaibashi, Osaka, the most well-known shopping district in the city, there is a small hair salon called Yumeya. Its owner, Yumeko Yume, is an avid fan of the Japanese 1960s and 1970s – the early Shōwa era. Opening the inorganic yet nostalgic stainless steel door, you will find a fancy space covered in shades of pink with retro music playing in the background.

Yumeko opened her salon here in 2000, with funds she saved from working part-time at public baths and for several salons for about five to six years. ‘I was so young at the time that it was easy to be optimistic about my business,’ she says. Inspired by one of the beauty salons she had worked at before, Yumeko only sees one customer at a time, which is rare even in Japan, a country with a staggering amount of beauty salons.

One of the salon’s main features is its specialisation in hair styles from the 1960s to the 1970s, which Yumeko has been fascinated by since high school. ‘I was interested in the music and manga of the time, but most of all, I loved the fashion scene,’ she explains. ‘I didn’t have a lot of money growing up, so I used to buy all kinds of retro-looking second-hand clothes, like patterned shirts and bell-bottoms.’

As an antiques collector, one of her most treasured items is a vintage hair curler. She says, ‘I bought it at a flea market, had it repaired, and still use it at my salon. My mother used to have a curler just like this one, and I adored it.’

When it came to the interior design, Yumeko was adamant that she would maintain the singular style she had honed over the years. In her own words: ‘If I’m going to do this on my own, I’ll do it my way.’ The art deco-style mirror that sets the shop apart was custom-made based on the design of one of her favorite earrings. The green chair, as striking as the mirror, is made by a Scandinavian designer. ‘I love the way it looks, but I found it very uncomfortable to use. On my first day, I ran out and bought a chair specifically for the beauty salon,’ she says with a laugh.

More than half of her customers are so-called ‘Shōwa maniacs’, people who love the culture of Japan's Shōwa era. They collect items from that time and wear fashion that faithfully reproduces the clothing of the era. Many of them visit the salon for special occasions, such as weddings, or dress-up events held within the Shōwa fan community.

‘In addition to Osaka, there are also many customers from other parts of Japan, such as Kobe,’ continues Yumeko, ‘and of course, there are also some people who come in for daily haircuts, which makes me very happy.’

The requests from these enthusiasts are diverse and specific. Some bring in photos of popular actors of the time and ask for a ‘millimeter-by-millimeter’ likeness, while others show reference images of characters from manga, such as comics by Osamu Tezuka and Aim for the Ace! by Sumika Yamamoto. Yumeko says that basic fundamental skills are necessary to accurately recreate such Shōwa-era hairstyles. ‘The first hair salon I worked at had a variety of customers, from the young to the elderly. I think the fact that I was trained in the essentials there helped me to develop my skills today.’

In addition to running a hair salon, she also organizes events for Shōwa enthusiasts, some of which focus on music from that era, and Shōwa-themed flea markets in a venue that still retains the interior design of an old cabaret to this day.

She adds: ‘Osaka is very competitive, so you never know when a place will go bankrupt. The interior is really cool, and I want it to keep it going somehow, so I try to hold events that make it attractive for young people to come. It’s not that I have any big ambitions to pass it on to the younger generation, but I would be happy if the community could expand, even if only a little.’